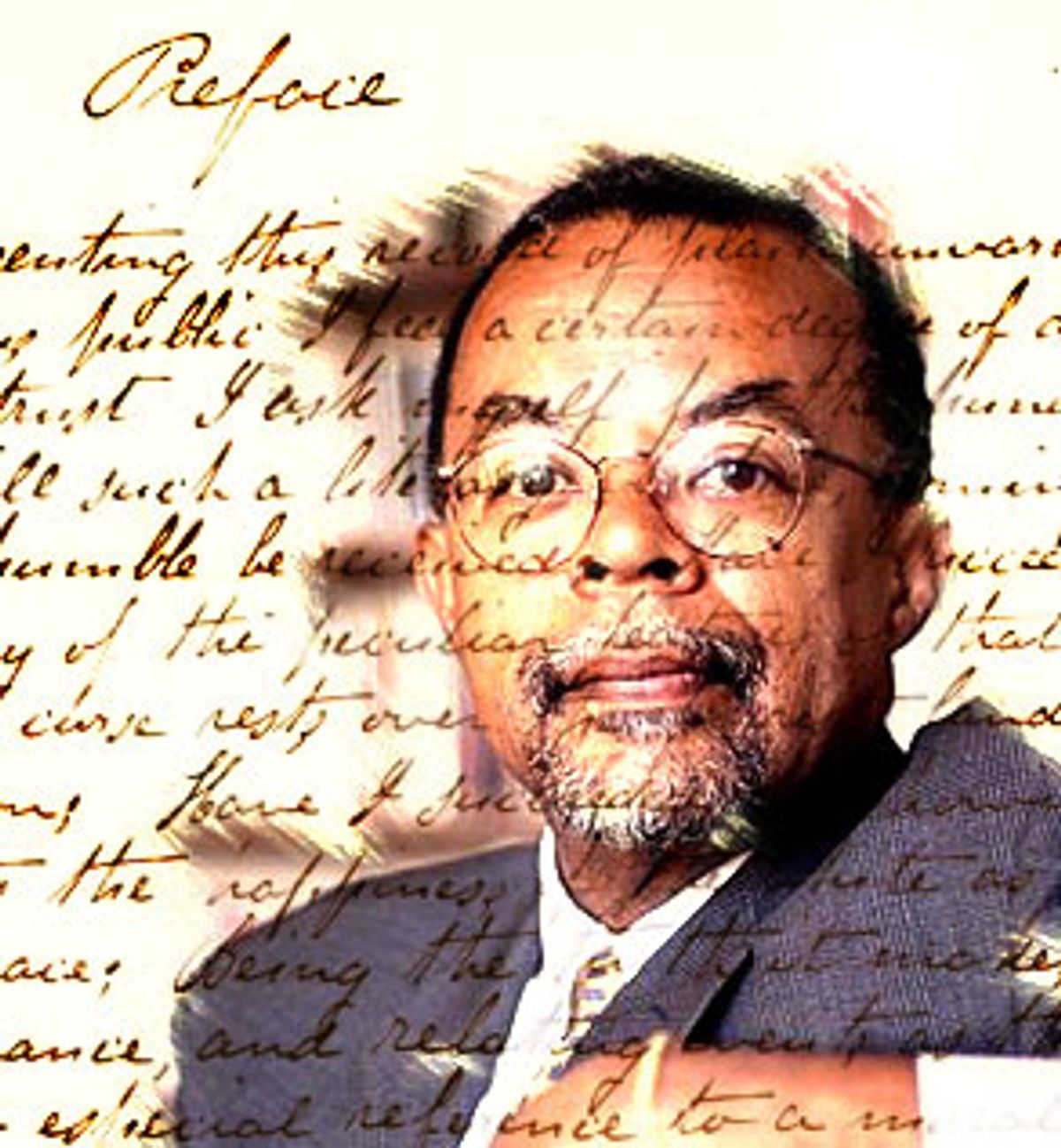

If Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. is correct, his recent literary find, a manuscript called "The Bondwoman's Narrative," recently published by Warner Books, isn't just the only known novel written by a fugitive slave; it's also the first novel ever penned by an African-American woman. Much is unknown about the book, including where and when it was written. However, the biggest mystery is the author herself.

After having hip-replacement surgery in early 2001, Gates, the W.E.B. Du Bois professor of the humanities and chair of Afro-American studies at Harvard University, was suddenly faced with an abundance of time on his hands. On sabbatical, he spent most of his days reading. Gates had begun receiving catalogs from New York's Swann Galleries, one of the foremost auction houses for African-Americana. One day, while perusing their catalog, he noticed a handwritten manuscript for sale, one purported to be an authentic "fictionalized biography," thought to date from the 1850s, signed by an escaped slave calling herself Hannah Crafts. Its history could be traced back to the 1940s, when it was owned by Dorothy Porter, the African-American scholar.

Gates was immediately excited. He had become well-known for authenticating and republishing Harriet Wilson's 1859 book "Our Nig," then the earliest known novel by an African-American woman (Wilson was a free woman, having been born in the North), and he felt that this particular auction lot might offer an even bigger discovery.

First, however, he had to figure out how to afford it. Most publishers Gates talked to weren't interested in providing financial resources unless the manuscript could be authenticated. Could Gates prove, for example, that the manuscript was as old as Porter believed? Could he be sure that it was indeed the work of an African-American and a fugitive slave? Authors of the period frequently published novels under false names and identities -- women authors publishing as men, and vice versa, and white authors occasionally writing fiction told from the perspective of blacks. However, Gates wouldn't be able to convincingly authenticate the book without first purchasing it.

"It was enough for me, as I say in the introduction, that Dorothy Porter thought [Crafts] was black. Dorothy Porter, as we say, 'did not play,'" Gates says. "She was a great scholar, and a bibliophile. To me, if Dorothy Porter thought [Crafts] was black, then she probably was black. There is absolutely no reason to pretend you are black today if you're white. No financial reason, no professional reason. If that's true, why would someone do it in the mid-19th century? The number of fictional slave narratives [written by whites] is tiny, and each of them was quickly outed. If a woman said she was black in the 19th century, then nine out of ten times she was black."

Finding no help from publishing circles, Gates decided to go it alone, even though he feared the book might fetch $50,000 to $100,000. Well, almost alone.

"A friend of mine, Richard Newman, went and bid," Gates laughs. "I was still house-bound at the time. I waited and waited and waited and waited. Finally he calls late at night, after I had lost like five pounds. I said, 'Dick, did we get it?'

"'Did we get it?' He goes, 'Oh yeah, we got it. First bid! I just decided to wait until it was over.'

"I wanted to kill him!"

In the end, Gates purchased the tattered manuscript for the bargain-basement price of $8,500 plus commission. Reading it, Gates felt an overwhelming sense of certainty as to its authenticity. "The Bondwoman's Narrative" tells the first-person story of a female slave named Hannah Crafts, like the novel's author, who escapes plantation life in Virginia and North Carolina, travels to Washington and ultimately winds up married to a minister and working as a schoolteacher in a free black community in New Jersey. Like Porter, Gates was struck by how, unlike white writers of the period, Crafts introduces her characters as human beings first. "Only," Porter wrote, "as the story unfolds, in most instances, does it become apparent that they are Negroes."

"You 'have to go there to know there,' as Zora Neale Hurston says," Gates recalls. "The evidence was overwhelming that [Crafts] was who she says she was. Just the thing about introducing characters as human beings and then telling you later they were black. Nobody did that. No white writer did that."

After purchasing the book, Gates found an interested -- if wary -- potential publisher in Warner Books. "Time Warner said, 'We have to date this,'" Gates says. "They had been burned by the Jack the Ripper diary fraud and then the Hitler diary fraud."

After carefully copying the book onto microfilm, Gates first visited with rare-manuscript dealer Kenneth Rendell, who helped expose both the Hitler and Ripper frauds. Rendell too believed the book to be an authentic work and recommended that Gates contact Joe Nickell, Ph.D. Nickell is the author of numerous books on literary sleuthery and is a senior research fellow at CSICOP -- the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal -- where he has successfully debunked thousands of claims of paranormal activity, weeping icons of the Virgin Mary, and all manner of Mulder/Scully material. Nickell was also another key figure in exposing the Jack the Ripper diary fraud, and a recommendation from Rendell was more than enough to inspire Gates' full confidence.

Gates had the manuscript hand-delivered by a courier to Nickell, who began an exhaustive weeks-long examination of the book. Gates, meanwhile, set about examining census records from the Library of Congress and the Family History Library of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and others. The story began to slowly piece itself together.

The first major break came when Nickell called Gates with a seemingly minor textual tendency he'd found that he believed might hold a store of information. In her manuscript, Crafts would refer to the slaveholder as "Wh----r." Later in the book, Nickell noticed Crafts would fill in the missing letters and use the full name (Wheeler) outright, which he felt indicated the author's increasing confidence about using her slaveholder's real name. Soon, Gates found out that that a slaveholder named John Hill Wheeler owned land in Murfreesboro and Lincoln County, N.C., where the beginning of Crafts' narrative is set.

Meanwhile, Nickell sequestered himself with the fragile book.

"My first impression of 'The Bondwoman's Narrative' was that it looked good as gold," says Joe Nickell. "But I've seen forgeries that looked equally as authentic. A forgery was unlikely here in some ways. The provenance traced back to the 1940s, where it was known to exist and sell for $85. When you consider that it had been around for quite some time and was sold in an era when it wouldn't go for much money, it wouldn't seem cost-effective. I wasn't over-suspicious of it, but I certainly pursued it [as if it might be a forgery]."

Nickell approached the authentication process using the multifaceted techniques he describes in his groundbreaking forensic book, "Pen, Ink and Evidence: A Study of Writing and Writing Materials for the Penman, Collector, and Document Detective."

"You take the approach that you need to clear your head of any preconceived notions or biases and just go at it in as complete a way -- and in as many directions -- as possible. You look at provenance, the ink, the paper, the internal evidence -- were these words in use at this time? Sometimes a forger may be very skillful with penmanship. However, such a talent may not have a scholar's knowledge of the language of a period, or he may get careless and use the wrong paper.

"You want to see that the handwriting looked like natural handwriting. The Jack the Ripper Diaries were filled with all sorts of curlicues and things to try and make it look sort of 'Ye Olde-ish,' to coin a phrase," Nickell laughs. "This looked like a natural, period handwriting. The ink had oxidized and browned with age, which is typical of an iron gall ink. There was a stationer's crest in the corner of some of the pages. Of course, the good forgers would give you that. So, I went at this with a fine-toothed comb. Actually, I went finer than that. I used a microscope."

Turning out the lights in his lab, and using an oblique light and a magnifier, Nickell was able to find an embossment of the Southworth Paper Company, which he was able to date thanks to documents he had records of from 1856 and 1860.

"Obviously, someone could find a piece of it today and use it, but to see such a quantity of it gave me a sense of the date," Nickell says. "I back-lit the pages with a fluorescent light and looked for watermarks, which there were none of. In the process, I found what was called an accidental watermark. It was a row of what looked like suture marks across the page. That's caused by the seam of the belt of early paper machines. I now know this is machine-made paper. I could also see, under ultraviolet light, mirror images of pages of that script glowing on the adjacent page.

"This kind of 'ghost writing' happens because the ink is quite acidic and degraded the cellulose of the paper touching it," Nickell says. "I consider it a good sign of age in a document."

The paper checked out as authentic. Nickell then turned his skeptical eye toward solving the puzzle of just who this "Hannah Crafts" was.

"I could see it was written with a quill pen by the brushstrokes," Nickell continues. "You can see the effect of the bluntness of her quill pen wearing down, and then being sharpened with a quill knife. I found evidence of writing sand in tiny little ink smears where she brushed it off the page. All sorts of little human elements that would add up. Her clearing excess ink off the page with her little finger, which was common of the era. Thomas Jefferson did it, for instance. She sealed pasted corrections with what appears to be a thimble ... all these little mundane human touches over and over again, on the right materials for the time."

Gradually, the different elements Nickell studied began to form an outline of the author in his head.

"I noticed she had poked pinholes through and sewn the paper in an amateurish binding attempt. I noticed that she had used what appeared to be small sewing scissors to cut the paper for her [paste-over] corrections. I'm putting all this together and thinking sewing materials. I recalled then that women of that period often had combined writing/sewing kits and writing/sewing desks. It was considered women's work in those days. I found a rather suggestive indication that this was probably a woman."

One day, Nickell phoned Gates with one of his frequent updates -- and a revelation.

"At one place in the book, [the narrator] mentions being in Washington with her slave owners, and she mentions seeing the equestrian statue of Jackson. That sort of leapt off the page at me, because I realized that might have very significant information as to date. That statue was erected in 1853, so the manuscript could not have been written before that. I then dated it as no later than 1861, again confirmed by the writing materials, due to the absence of any mention of the Civil War or secession. Gates found in Wheeler's diary an identical mention of the statue."

Nickell soon sent his findings back to Gates and Time Warner Books, both of whom were satisfied with the expert's findings. Gates in particular was overjoyed.

"We really went together like a double helix -- like parallel universes," Gates says. "Without that report, I would have found facts, but it wouldn't have as complete by far as it is now. My debt to him is enormous. I'm a big fan of that guy. That's why I insisted on printing the whole [of Nickell's report in the book] rather than summarizing it. It's like a work of poetry."

After Gates sent the book to various scholars, many signed on to help in the quest to find a historical record of Hannah Crafts. One, William Andrews, the E. Maynard Adams professor of English at the University of North Carolina, pointed out John Hill Wheeler's involvement in the Passmore Williamson case, in which Wheeler's slave Jane Johnson was aided by Williamson, an abolitionist, in her escape from the slave owner. Imagine Gates' surprise, then, to learn that Crafts mentions Johnson in her manuscript.

The discoveries kept coming. Through Andrews, Gates was also introduced to Bryan Sinche, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina who went on to discover Wheeler's library list.

"What's fascinating is that Wheeler's library contained about 10 slave narratives," Gates says. "There was not only Dickens and 'Uncle Tom's Cabin,' but also two different editions of Frederick Douglass, as well as slave narratives and 'A Key To Uncle Tom's Cabin.' This is the first time that we have an idea that a slave owner could give a hoot about the slave narratives published by the fugitive slaves. It was like a Cold Warrior reading 'Memoirs from the Bolshevik Revolution.' Maybe it was to keep up with what the opposition was doing, and maybe to discredit them.

"You notice when I talk about the gothic elements [in the novel], I say, this package echoes Horace Walpole's 'Castle of Otranto?' That book's in [Wheeler's] library. I say this passage or that one echoes Frederick Douglass? That book's in his library."

It's discoveries like these that kept excitement about "The Bondwoman's Narrative" steadily growing until Gates finally signed off on the finished galleys in time for the book to come out at the beginning of April 2002. Gates is confident that evidence of Hannah Crafts' existence lies somewhere in the shady folds of history, in census records, perhaps, or in someone's attic in New Jersey, the state Crafts' narrator lives in at the end of the book.

"'The Bondwoman's Narrative' is a unique, perhaps paradigm-changing text, unprecedented in 19th century American literature," says Andrews, one of the world's leading authorities on 19th century African-American literature. "Skip Gates' research provides compelling evidence that 'Hannah Crafts' was the first known African-American novelist. The discovery of the text in its unedited form is very important, because nothing like it exists in African-American literature from the mid 19th century. Manuscript versions of writing by major early African-American writers are extremely rare." Many works written by African-Americans of the time were heavily edited by white abolitionists before publication.

"My prime reason for publishing it now as opposed to later was that I had reached a dead end," Gates says. "I wanted to release it now so that scholars both independent and professional could have a go at it. If this book exists, if 'Our Nig' exists, then other things exist. It's just the way it has to be. They keep finding Mayan cities and tombs of pharaohs. They've got to find more manuscripts from black people in the 19th century. I'm confident of it. It's just the way it has to be."

Shares