It's been a nasty couple of weeks for New York's writing women, both real and imaginary.

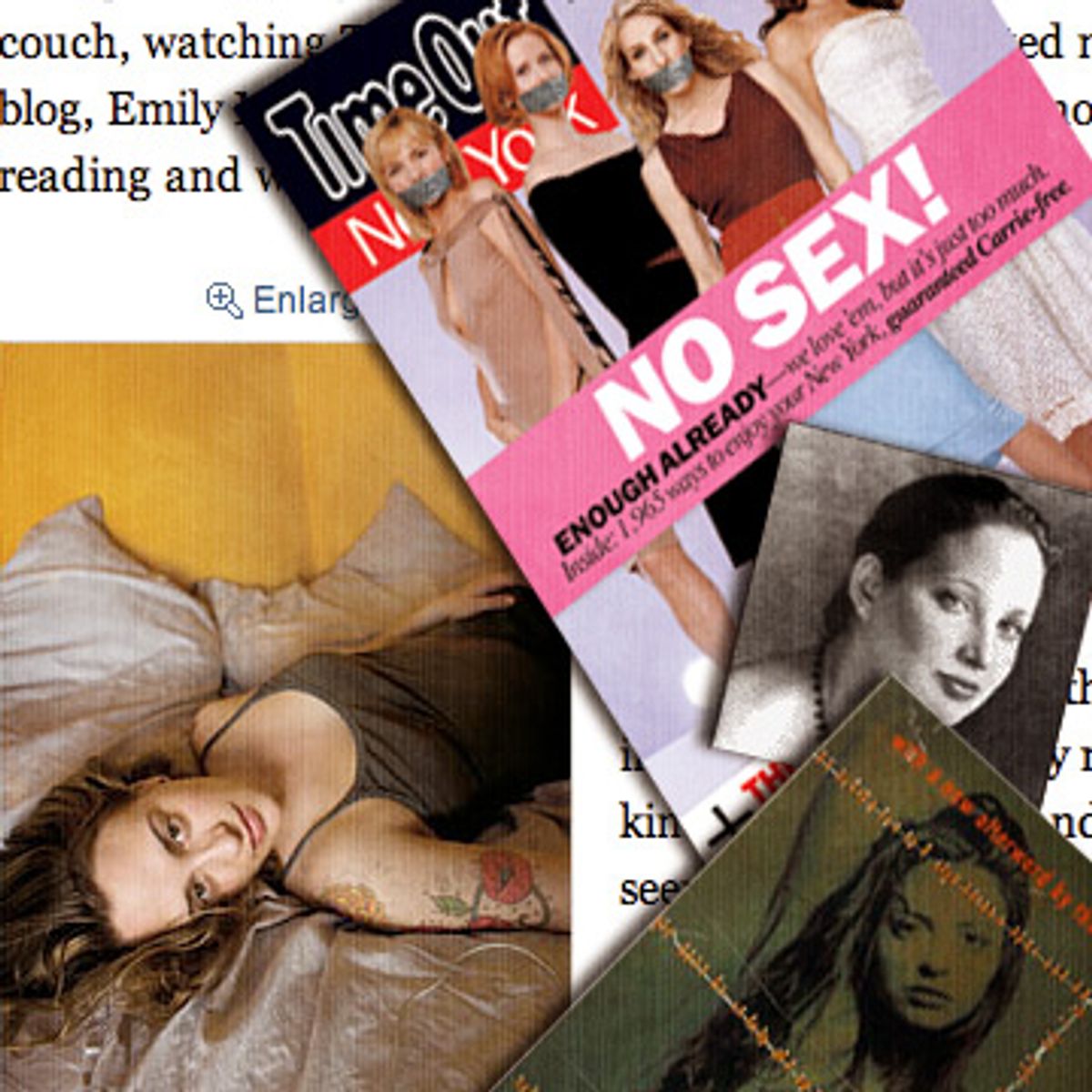

First came an anticipatory backlash to the big-screen debut of Carrie Bradshaw, the fictional and expensively shod sex columnist heroine of "Sex and the City." In the years since HBO created its hit show based on Candace Bushnell's New York Observer column, Carrie and her over-sexed girlfriends have -- to the dismay of many women who live in their city or toil in their professions -- become tutu'd cartoons, representing the assumptions people make about what single, professional straight women must be like: They are materialistic, horny squealers, hungry for brunch and husbands. Apparently, lots of women who don't feel in the slightest bit represented by the "SATC" ladies are not thrilled to see them back again, this time plastered all over their multiplexes. Time Out New York even ran a story whose cover featured the show's stars in evening wear, with duct tape over their mouths.

Over at the popular women's blog Jezebel, managing editor Anna Holmes reasonably queried, "What, pray tell, was so damn groundbreaking about a group of narcissistic rich white women with a love of shopping and gossiping about their sex lives?" Last week, Holmes handed the task of watching all six seasons of the series to blogger Emily Gould, a former Gawker editor who prides herself on having coined the term "Scary Sadshaw" in derisive reference to the show, its adherents and, in her words, "all the thirtysomething ladies who desperately need TV role models to justify their one night stands, shoe-splurges, and bloggy confessions about same." Gould's early posts from the "SATC" front lines were comically dismissive of the show, illustrated with an image of Parker as Bradshaw, lying in a rumpled bed, wearing a tank top, and pointing her finger to her head like a gun.

How appropriate. In the same week that Gould was covering this "SATC"-critical terrain, she graced the cover of the New York Times Magazine -- tank-topped, tattooed and lounging upside down in mussed bed sheets. The cheesecakey cover shot advertised Gould's first-person story, an 8,000-word exploration of what Gould "gained -- and lost" by divulging details of her romantic and sexual life on the Internet. The very readable piece had the voyeuristic feel of a precocious, neurotic teen's diaristic musings; it was all crushy and naive, with ample reference to breakup sex and therapy and panic attacks.

Response to Gould's story was even chillier than Gould's regard for Bradshaw and her buddies. The typically staid Times comments section roiled with readers who were practically apoplectic in their loathing for Gould. "This article was nothing more than the ramblings of a moronic juvenile who calls herself a writer," wrote Joseph from Manhattan, while a woman named Beatrice complained about the "total narcissism, self-involvement, and ego-mania" she believed the article revealed. And a woman claiming to be Gould's age wrote, "Please stop embarrassing our generation with mindless prattle."

In the days surrounding the publication of the piece, Gould's "SATC" critique turned increasingly self-referential. Her history of ragging on "Scary Sadshaw" was quickly becoming ironic. Gould hated Carrie and her ilk for being shallow, self-absorbed, exhibitionistic, moony over men; now readers hated Gould for all the same reasons!

What provokes such fury, over Carrie Bradshaw, and -- for a flash -- over Gould (barring a book deal and TV show that will turn her meanderings into cultural furniture) is that in a media landscape in which there are a severely limited number of spaces for women's writing voices, the ones that get tapped become necessarily, and deeply inaccurately, emblematic -- of their gender, their generation, their profession. More annoying -- and twisted -- is that those meager spots for women are consistently filled by those willing to expose themselves, visually and emotionally. And not accidentally, by those willing to expose themselves in a way that is comfortable, and often alluring, to many of the men who control the media, and to many of the women who consume it. There is a storied history of bright women writers (many of whom are mentioned in a New York Observer article this week), from generational confessionalists like Joyce Maynard and Elizabeth Wurtzel to cultural critics like Katie Roiphe to novelists like Lucinda Rosenfeld and Marisha Pessl, who have been raised up as media darlings, photographed in appealing poses or in titillating features, and then ripped apart by critics (including, on more than one occasion, me).

When we are fed -- and gobble up -- stories by or about single urban working women, those exotic and potentially threatening creatures presented to us are often doing things like confessing their self-doubt, discussing their sex lives, lying on rumpled sheets looking pretty.

Any suggestion that this is anything other than a double standard is false. When magazines feature stories about writers like those smart young men over at N+1 (as the Times magazine did a few years ago) those men are not typically photographed blogging in their beds; when, as the Observer suggested, we read a first-person confessional by Philip Weiss (who wrote recently for New York about his extramarital sexual yearnings) we are not treated to a bare-limbed image of him, or any image of him at all.

We are mired in a repetitious pattern of hate, jealousy and resentment toward those who are plucked by media powers and come to stand -- however inefficiently -- for the rest of us in the cultural imagination, securing the top spots, the best exposure, the prime media real estate in exchange for openings veins of feminine vulnerability.

Just as Gould is infuriated by all those "Scary Sadshaws," wandering around in search of baubles and boys, I find it maddening to think of grandparents around the country picking up their Times magazine, getting a load of Gould, and thinking, "So that's what that single professional city life is about! Boyfriends and blogging about them!" Maddening to think of doddering new media critics having their worst suspicions about the self-obsessed downfall of journalism confirmed by Gould's me-tastic assertion that while writing for Gawker, she found that "injecting a personal aside into a post that wasn't otherwise about me ... kept things interesting for me." Maddening to have to wonder -- Carrie Bradshaw-style -- if Gould's story would have run had she not been beautiful, and maddening to then hate oneself for having had to wonder that at all.

But perhaps most maddening is the way the buildup of critical attention to a piece like Gould's -- or to a cultural phenomenon like "SATC" -- only affirms that certain kinds of women, and only those kinds of women, are worth elevating to begin with, in part because of the delight people take in tearing them down.

Look no further than the Times' own Q&A session, in which Gould answered questions from readers. It was unclear whether these questions were selected by the paper, or cherry-picked by Gould in some kind of martyred, self-immolating frenzy; either way, the writer, who might otherwise have been celebrating her success, got bloodied. "Has this been a wakeup call for you that nobody cares about any of this? I certainly don't. I couldn't even bear to finish reading your blog (yes, it is a blog, not an article)" went one "question." Another reader "asked": "Like you, Joni Mitchell was extremely self-referential. Many people liked this at first, but they eventually grew tired of it. When she finally stopped writing about herself and turned her attention elsewhere, most people had already lost interest and moved on. Do you worry that the same thing will happen to you?"

No matter how angry you felt about Gould's piece, it was almost impossible to read the comments and not feel terrible: for her, about her, and about yourself for having even peeked. The process is exhausting, and not good for anyone, especially women who get stuck with some lame avatar they feel does not represent them, but whom they do not particularly feel like burning at the stake just for having been clever, lucky or talented enough to wind up drawing a spotlight.

We have to remember: There is nothing wrong with women writing about themselves, their youth, their indiscretions, their habits and values and personal development. Men have been writing about this stuff for thousands of years; they call it the canon.

And like their male contemporaries, a lot of this writing disappoints. When it does, there is nothing wrong with criticizing it. The thing that is wrong -- really wrong -- is when we forget that these kinds of stories are not the only ones that women have to tell.

So rather than being troubled by the fact that Gould -- or Bushnell, or Bradshaw, or whoever -- has the spotlight, why not question why so few other versions of femininity are allowed to share it?

Shares