Nancy Drew's mother is dead. Like the mothers of fictional children from Oliver Twist to Harry Potter, she is dead so as to allow her child adventures no properly parented kid could possibly have.

This May, the girl detective's literary mother died, as well; Mildred Wirt Benson, who wrote 23 of the original Nancy Drew mystery stories, was 96.

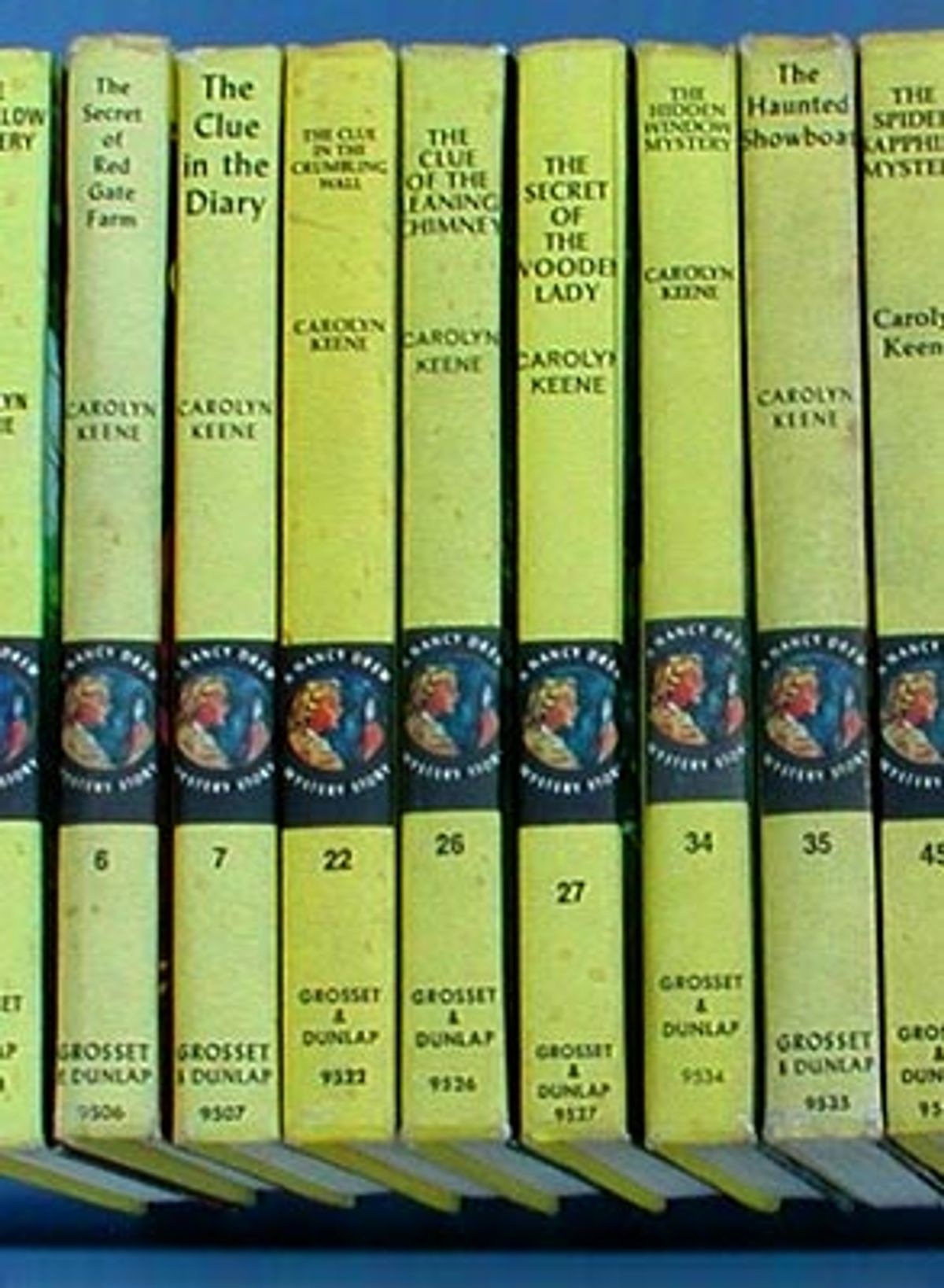

Back when I was 9 and my Nancy Drew mania was at its peak, my friends and I had already heard that there was no "Carolyn Keene," ostensible author of what are now well over 150 adventures (not counting spinoff series). Telling a child there's no Carolyn Keene is "like saying there's no Santa Claus," as Benson herself said to Salon in 1999, but some unkind grown-up did tell my friend Sunshine, and she told me. Together, we looked at the row of 50-some novels on the library's Nancy Drew shelf and reasoned that, come to think of it, no one person could write so many, even if she wrote for her whole entire life! (Publishing history is sketchy, as it is with most series fiction, but it looks like there were 56 titles available in different variations until 1979, when Simon & Schuster started publishing new Nancy Drews in paperback, one every other month.)

Still, Sunshine and I thought, maybe some of the books were more "real" than others. Perhaps there was a Carolyn who wrote the very first adventure -- "The Secret of the Old Clock." Maybe she also wrote "The Hidden Staircase" (No. 2) and "The Secret of Shadow Ranch" (No. 5) in which a "pretty, slightly plump blonde" named Bess and an "attractive tomboyish girl with short dark hair" named George first appear, ready to help "Titian-haired Nancy" on her "dangerous assignments."

Carolyn Keene. Her name sounded young and fresh and blond. That "real" Carolyn invented this world full of "delicious" meals and "attractive" boys, a world where three 18-year-old girls drove around town in Nancy's blue roadster, their trim clothes offset with matching shoes and beige accessories. A world where changing into a fresh dress for dinner and showing one's blue eyes "to advantage" wasn't incompatible with wandering around at night shining flashlights into the woods, chasing after shady-looking men and rescuing helpless innocents from terrifying enemies.

After the first few books, Sunshine and I thought, when the series got so popular, Carolyn had to turn some of the writing over to other people: bright young women in smart wool suits who sat in front of typewriters late into the night, banging out these clever, scary mysteries. "Ghostwriters." We knew the word, and it sounded perfect -- though we usually asserted that the early stories were the best. The most authentic.

In reality, Carolyn Keene and Nancy Drew were the brainchildren of Edward Stratemeyer, owner of the Stratemeyer Syndicate and creator of the Bobbsey Twins and the Hardy Boys. He hired Benson (nee Wirt) to write about a girl detective, paid her $125 per book, then died the year the first one was published (1930), leaving his daughter Harriet Adams to supervise the series and later write many of the novels herself. But it was Benson who created the Nancy that captured me and my friends. And she really did write for her "whole entire life": Until her death she penned a column for the Toledo Blade, and she authored more than 130 books -- more than Sunshine and I ever would have thought possible.

Fans of Nancy Drew tend to say they love the character because she is a proto-feminist, a good role model for girls. The young sleuth is courageous, agile and smart. Nancy Picard, author of the Jenny Cain mysteries, writes that "the original Nancy Drew is a mythic character in the psyches of the American women who followed her adventures as they were growing up. She may have been Superman, Batman and Green Hornet, all wrapped up in a pretty girl in a blue convertible ... [She] is our bright heroine, chasing down the shadows, conquering our worst fears, giving us a glimpse of our brave and better selves, proving to everybody exactly how admirable and wonderful a thing it is to be a girl."

OK, true enough. Nancy certainly solves mysteries, rescues people, takes fearless action. But rereading the pile of Nancy Drews I found at my local library, I began to think the books' appeal lies in something other than feminism.

The character is much older than other heroines intended for preteen readers. When I read Nancy Drew, I was also reading about Pippi Longstocking, Ramona the Pest and Harriet the Spy. Nothing with grown-up protagonists. Nothing, even, with protagonists old enough to drive.

There is almost no description in the novels, with the two exceptions of clothing (matching ensembles, fun "Indian costumes") and food (lobster, hot fudge). There is very little atmosphere and no imagery. When Nancy ventures out at midnight to search for a missing girl in "The Clue of the Broken Locket" (No. 11), "the thick woods shut out the brilliant moonlight" -- and that is every word of scene-setting we get.

George has no personality traits aside from athleticism and occasional unkind critiques of Bess' weight ("Eating is really a very fattening hobby, dear cousin"). Bess has little more: occasional glimmers of giggly timidity and a tendency to eat sundaes when the other girls choose soft drinks. Nancy is the median between their two moderate extremes, and in that sense is even more featureless than they. George is a tiny bit too thin and too masculine; Bess is a shade too plump and too feminine. Nancy Drew is just right, and though she's always the best at everything -- from horseback riding to water ballet, to name the two that impressed me most when I was 9 -- she has no interests, speech patterns or personality quirks that carry over from book to book.

The girls also have no troubling feelings besides curiosity and, occasionally, fear. They never get angry at one another. Nancy never misses her boyfriend, Ned, who is often conveniently "in Europe" or at college. She doesn't mourn her lost mother. She doesn't have the self-doubt that plagues most contemporary teenage characters. What she does have is a seemingly endless flow of cash. And a nice car. And the chance to take excellent vacations because she is neither in school nor gainfully employed. She has fabulous clothes, and is portrayed -- in the yellow hardcover editions that can still be easily found at the public library -- in sporty, clean-lined drawings that recall fashion illustrations.

In short, the Nancy Drew stories are both pure mysteries and glamour fantasies. The lack of emotion and character, combined with trademark cliffhangers at the close of every chapter -- "Within seconds, the canoe sank!" "Just then the agonized scream of a woman came from the house!" -- make the books read like exercises in pure plot-making. At the same time, the old illustrations are still reprinted because the neat little outfits and carefully constructed hairstyles are part of the books' appeal. Food, clothes and vacations to dude ranches, summer cottages and historic castles -- it's all closer to reading old copies of Mademoiselle magazine than it is to Agatha Christie.

Unlike the hardcovers, the contemporary paperbacks have no pictures except cover art that makes Nancy look more like Alicia Silverstone than Joan Fontaine -- but the prose style is remarkably similar to that of the Benson stories. Same digs at Bess' weight; same cool clothes for Nancy; still no job, no school; great car, great travel; no atmosphere or description other than meals and outfits. In short, the same fantasy.

Ironically, since her heroine had such a sense of entitlement and always proudly identified herself as a detective, Mildred Benson never collected royalties and was contractually bound from admitting she was a series writer until a court case in the 1980s revealed it. Also ironically, the yellow hardcovers, which I have always thought of as the "real" Nancy Drew books (as opposed to the contempo-romance-looking paperbacks) -- are actually revised, condensed editions of the stories as written by Benson and the other early Carolyn Keenes. In 1959, Harriet Adams had them edited to uniform length, excising racial slurs and other unpleasant bits. Nancy's age was also raised from 16 to 18 and her hair color changed: blond in the originals, she is "titian-haired" in the yellow books.

To find the original stories as Benson wrote them would take probably only a few minutes on eBay, but a 1930 blue-covered first edition of "The Secret of the Old Clock" is worth $1,500, whereas the revised, yellow-covered 1959 edition is worth $10 to $25. Libraries have the yellow. Bookstores have the yellow. Therefore this article, my memories and most of Mildred Benson's legacy are built primarily on a Nancy rather different from the original. Benson told Salon that the Adams edits "made Nancy into a traditional sort of a heroine. More of a house type. And in her day, that is what I had specifically gotten away from."

And yet, it is the yellow books that matter most, because they are the texts that have infiltrated the collective imagination of anyone born after, say, 1952. (That is, unless you are a true fan, or a collector, or a book historian -- in which case they are corrupt and second-rate.) In any case, Benson's passing is just a symbol. She wrote some of the books, but not all. She wrote some of the prose we see on the page, but not all. She was the "real" Carolyn Keene, and she was not. Her Nancy is the "real" Nancy, and it is not. The essence of the girl sleuth -- if the essence of a fictional character is somehow located in authorship or in textual sanctity -- remains an unsolvable mystery.

Shares