As any kid who ever pulled a thin, slithery rayon tunic printed with cheesy designs over his head or felt his breath condensing on the inside of a vacuformed plastic mask knows, a Halloween costume can be a very flimsy thing. Yet, however humble, these get-ups have power. At the very least they spell a big bag of free candy, and at best they promise a temporary vacation from yourself. As sugar-smitten as I and my four siblings were (and we could parse the advantages and drawbacks of various candies -- from Pixie Sticks to Milk Duds to miniature chocolate bars -- like medieval scholastics classifying the angels), the most important question was always, "What are you going to be for Halloween?"

Some of the first costumes specifically manufactured and sold for the holiday in the 1920s (masquerade is not, surprisingly, a very hallowed Halloween tradition) were made out of crepe paper, and surely none of them survive. If one did, Phyllis Galembo would own it. Galembo, a New York photographer, has a collection of over 500 costumes, some dating back to the 19th century (and perhaps not, strictly speaking, Halloween costumes), several dozen of which appear in "Dressed for Thrills: 100 Years of Halloween Costumes & Masquerade." You could say that Galembo has photographed them, but it would be more accurate to say she's transfigured them, because her camera has infused them with an eerie totemic quality that distills the murky glamour of Halloween itself.

Galembo, who has photographed Candomblé priests and priestesses in Nigeria and Brazil, has a feel for the way setting, lighting and a sense of ceremony fill objects with significance. Some of the costumes in "Dressed for Thrills" are modeled (by children, mostly) in front of theatrical sets; others are suspended in midair or laid out like the next day's work outfit. Employing an elaborate long-exposure method, Galembo used a hand-held light to paint a glow around or behind the costumes so that they appear luminescent or seem to be emerging from a primordial gloom. The backgrounds can be blurrily evocative of midnight swamps, circus tents or burning haystacks -- or they can be solid colors with a luscious depth, as if made of tinted smoke or water.

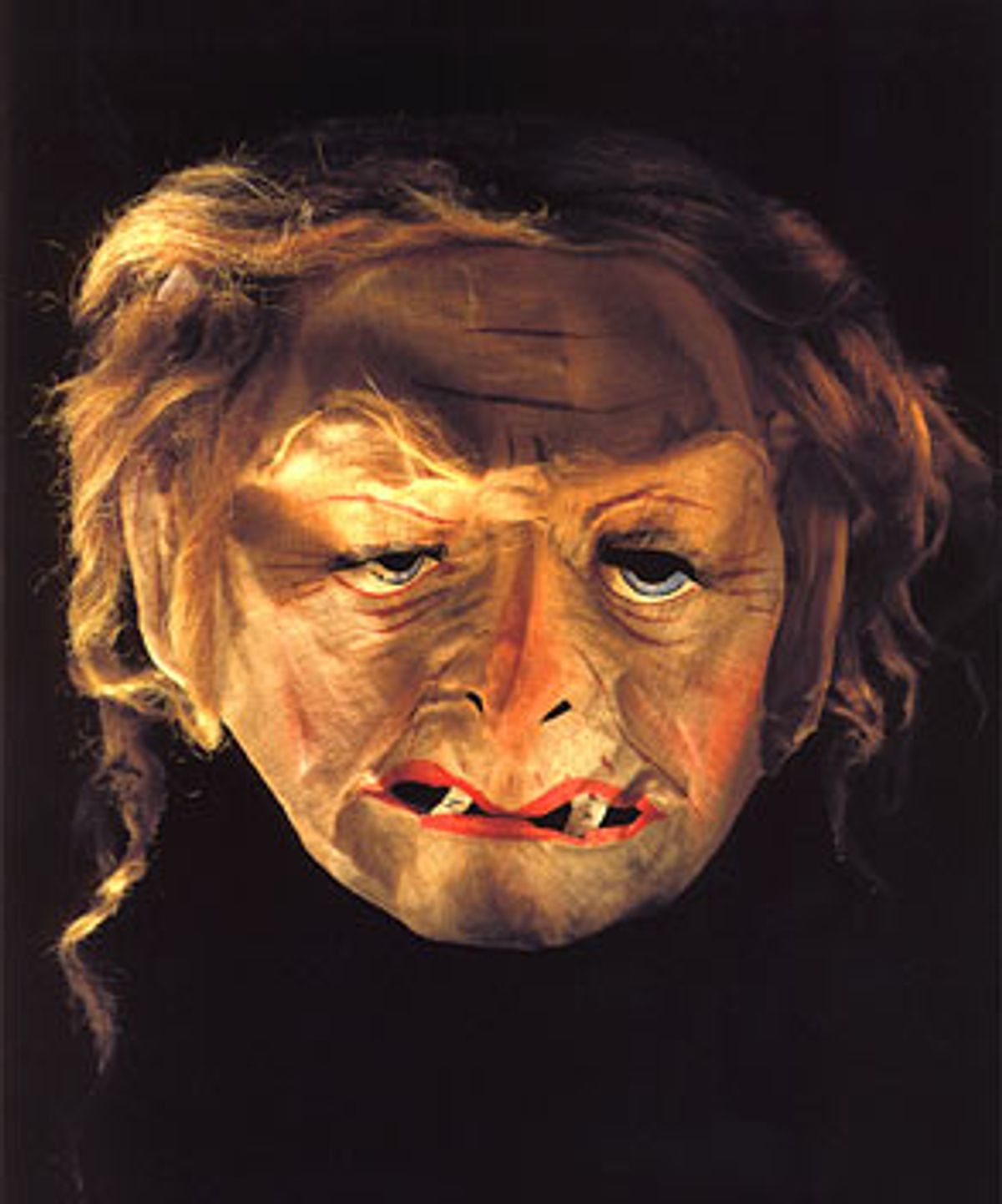

Some of the oldest disguises here -- a handmade cotton dog mask with a cork for a nose, a Depression-era ghost mask uncomfortably reminiscent of the hoods worn by condemned men on the gallows -- are little more than painted bits of cloth. Others are complex hand-sewn affairs like a calendared jester get-up that must have taken days to construct. Before the plastic masks that appeared in the 1950s and '60s (they're still fairly common today), Halloween masks were made of stiff cotton or linen buckram (basically, a starched gauze) steamed over a mold. These, now decrepit and faded, make for the creepiest images in "Dressed for Thrills." No glow-in-the-dark "scary" monster costume from the '60s can match the chills of a 1920s Marie Antoinette mask (complete with a tower of white wool hair), which looks like something an unspeakably depraved European would wear to a Satanic orgy.

Halloween costumes were one of the few store-bought products my siblings and I considered inferior to homemade. My mother, armed with Simplicity patterns and a Singer sewing machine, really went to town on this, her favorite, holiday. She, along with the manufacturers of novelty sombreros, probably kept the market for dangling pompom trim artificially inflated for years. The footed black cat costume she made for me -- with a yard-long stuffed tail! And a hood with ears! -- might just be the best outfit I've ever owned.

We scorned the lame rayon jumpsuits and boring masks our less fortunate playmates purchased at the drugstore, but pictured here -- Hey, I remember that vampire mask! -- they've acquired a campy charm. Galembo's collection includes some still-in-the-box products of the Ben Cooper and Collegeville companies (the latter is still around), including a shrieking skull mask with a bouffant of green hair and Buddie Beatnik, whose pipe and full flocked beard suggest a profound confusion on the part of the folks at Ben Cooper Co. about the difference between beatniks and old-time hobos. (Among the slogans plastered on Buddie's chest is the word "Expresso.") And it turns out that the designers of boxed costumes weren't incapable of wit; Collegeville made a Visible Man costume with a map of the circulatory system and internal organs printed on the jumpsuit and a clear plastic mask with red and blue veins painted on it.

Galembo's interest in "the spiritual and transforming power of ritual clothing" ends with what she calls the "mostly licensed and quite commercial" costumes of the 1980s. That condemnation doesn't make much sense, since pop culture figures like Little Orphan Annie, Mickey Mouse and Howdy Doody have been part of the masquerade vocabulary since the custom of Halloween costumes began, as "Dressed for Thrills" documents. Besides, the very gruesome, horror-movie-inspired latex masks that came into vogue in the 1980s are, however vulgar, more imaginative than the Day-Glo jumpsuits and vacuformed mask costumes Galembo does celebrate. What today's latex monstrosities with their dangling eyeballs, exposed brains and extra heads are not, though, is old. Part of the magic of Galembo's costumes is their age, the fact that they weren't meant to last and yet here they are, rendered precious by the passage of years. In all likelihood, the people who originally wore them have died or grown up, leaving behind these answers to the all-important question "What are you going to be for Halloween?" -- these ghosts of a good time had long, long ago.

Shares