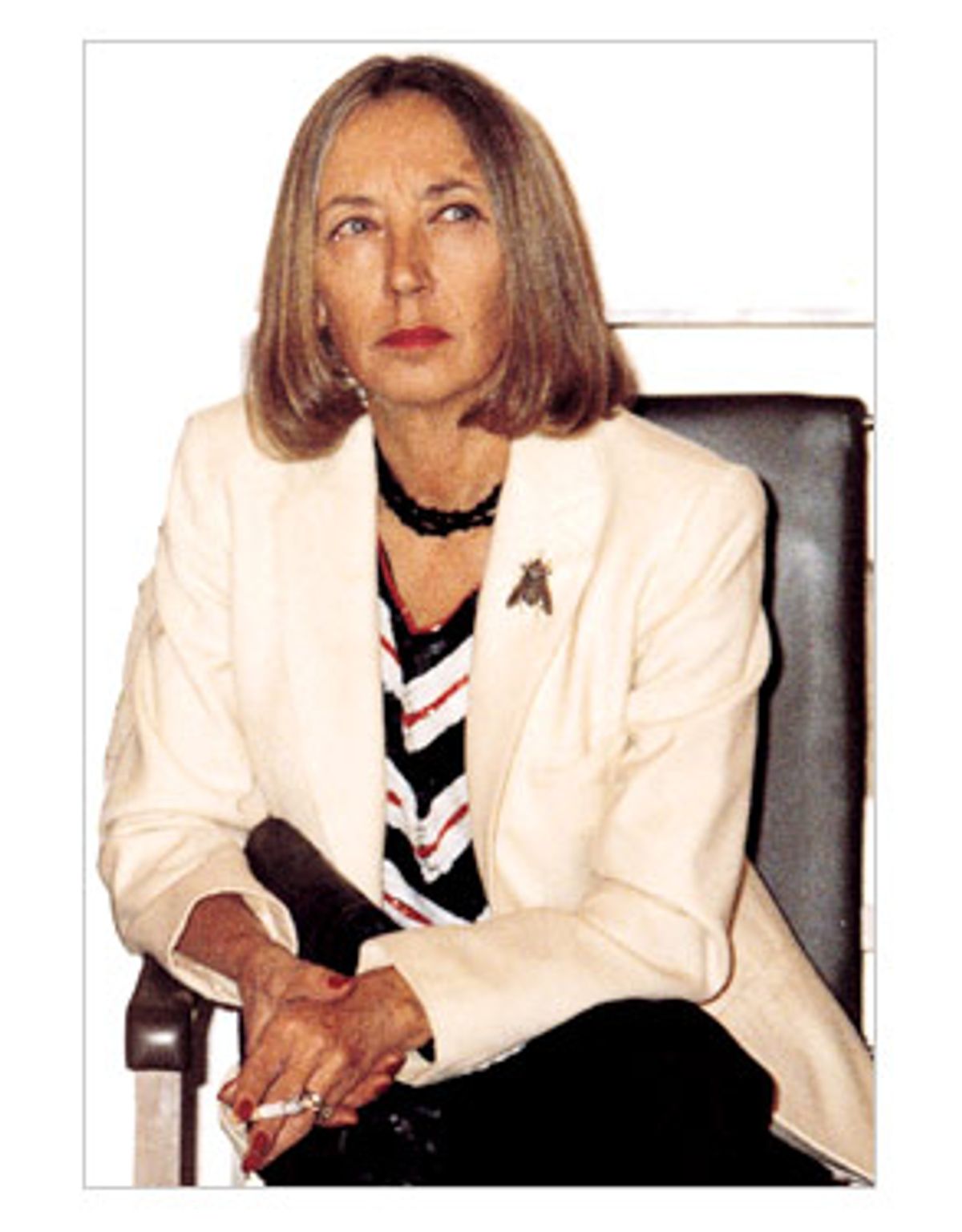

"Immediately he caught fire as if he had seen Greta Garbo throwing off her black glasses and parading in a licentious striptease on the stage of La Scala." That's Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, describing the reaction of the editor in chief of a major Italian newspaper when she told him she would break a 10-year silence to write a piece about Sept. 11, a piece asserting what she sees as the unbridgeable divide between the Islamic and the Western worlds. To drive home the comparison, the author photo on Fallaci's "The Rage and the Pride" -- Fallaci in Garbo-like black glasses and hat, seemingly caught by surprise in the backseat of a car -- replicates all those paparazzi shots of the aging Garbo caught on the streets of New York. She knows what's going on in that editor's mind when she agrees to write for him. She knows he is imagining "my readers already lining up to buy the newspaper" or "to crowd into the stalls and the boxes and the gallery of the theater."

The mention of La Scala is not an accidental one. Camille Paglia, another diva of the page, said she based her concussion-grenade prose on '60s acid-rock guitar. For Fallaci the model is opera, with its bigness, its overdramatization, its rising and falling waves of emotion. She writes not to convince or to persuade but to overwhelm, to storm the barriers, to sweep us into a state of transcendent rage. "The Rage and the Pride" is not just Fallaci's aria; it's a full-scale production where she assumes all the roles herself: a pitiless Cassandra, the tragically wronged heroine, the warrior who will turn vengeance into a scourge, burning the nonbelievers and laying waste to their lands with her violence and her passion. If she could find a way to hand out arms to her readers after they put the book down, she probably would.

Sept. 11 would seem the last event on which it is appropriate for a writer to deliver a performance. A few months ago in the New York Times Book Review, Walter Kirn suggested that the only fitting reaction to all of the "I was feeding the cat when the phone rang and a friend told me to turn on the TV" writing that Sept. 11 produced is: "Who cares?" The magnitude and horror of the event make the small-scale personal reaction seem almost offensively irrelevant. So how can we possibly justify the egomaniacal reaction that Fallaci has?

"The Rage and the Pride" is double the length of the article that Fallaci delivered to that Italian newspaper, and it's abetted by a 53-page introduction. She doesn't miss an opportunity to point out that she has been warning of the dangers of what Christopher Hitchens has termed "Islamo-fascism" for years. Fallaci, who calls herself a political exile and has been living in New York for some years, compares this book to a 1933 lecture given by Professor Gaetano Salvemini at the Irving Plaza Hotel in which he decried the danger of Hitler and Mussolini.

And Fallaci doesn't hesitate to bring up the peril in which she has placed herself by speaking out. She says that a French "ultra-leftist" Muslim association asked a French court either to confiscate this book or to label each copy with a warning similar to the one found on cigarettes cautioning that it may be hazardous to the reader's health. The president of the Italian Islamic Party has written a book called "Islam Punishes Oriana Fallaci," in which (she claims) he exhorts his followers to kill her. Fallaci also claims that the author's "brothers" (it is unclear whether she means that literally or as a synonym for comrades) are sending her daily death threats.

Yet she will go on, laying aside the novel she has been working on for 10 years (she calls it her "child"), ignoring the cancer from which she has long suffered. The very writing of the book is presented to us as a heroic struggle in which she draws on her years of experience covering wars, traveling the world, fearlessly speaking out. She imagines the book will send her fans into raptures and her enemies into a fury. Basically, she is picturing a world in which everyone is hanging on the utterances of La Fallaci. She even imagines the Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi trembling in fear of the judgment she will unleash on him.

It would be wrong to underestimate the levels of ego and arrogance at work in "The Rage and the Pride." Or the xenophobia, the periodic lapses into racism, the outright paranoia. It would also be wrong to dismiss the book. It's not something that journalism teachers would ever teach their students, but we should not underestimate the uses of deliberate overstatement. Sometimes you need drama and polemics to break through indifference, received opinion, the limits that politeness imposes on discourse.

That does not relieve readers of the responsibility of making distinctions. We should feel queasy when Fallaci writes that Italy is not big enough to be a melting pot in the way America is and that the country is in danger of losing its national identity from the influx of Islamic immigrants. We should be appalled when she writes that the presence of Islamic butcher shops in Cavour has transformed the "exquisite city" into a "filthy kasbah." We should question what Yasir Arafat's "smelly saliva" has to do with reporting on his politics other than to reinforce the image of Arabs as dirty.

We should gag at the kitschification of Sept. 11 when Fallaci tells the story of an 8-year-old American boy who can no longer use the sight of the twin towers to guide him home and she writes, "If you get lost now, some good person will help you instead of the Towers." We should object to her ridiculing homosexuals as "devoured ... by the wrath of being half and half," or asking feminists who oppose the war on terrorism if they dream of being raped by Osama bin Laden. Or when she characterizes Albanian, Sudanese, Bengalese, Tunisian, Egyptian, Algerian, Pakistani and Nigerian immigrants as intruders who contribute to the drug trade and patronize prostitutes who spread AIDS. And we should recoil from the paranoia of asking if the passage fees of all Islamic immigrants to the West is paid by "some Osama bin Laden for the mere purpose of establishing the Reverse Crusade's settlements and better organizing Islamic terrorism."

Fallaci can imagine no Muslim who is not a threat. And though she may be linguistically correct when she ridicules the charges that she is a racist ("the problem has nothing to do with race: it has to do with a religion") there is enormous bigotry here nonetheless. Perhaps more bigotry than I've ever encountered in any other book worth reading.

Why is a book that makes you ashamed for its author, even occasionally ashamed to be reading it, still worth reading? Because for all its bigotry and paranoia, all of its ill-informed dismissal of Islamic history and culture, "The Rage and the Pride" is a bracing response to the moral equivocation, the multi-culti political correctness, the minimization and denial of the danger of Islamo-fascism that dogs the response to Sept. 11 and to the ongoing war on terrorism. (That is, if we can assume that war is still ongoing, if Bush, caught up in his plans to invade Iraq, still remembers that it is al-Qaida that poses the predominant threat to the West.) To understand how a book that contains much that is repugnant also has a cogent, coherent argument, we must put it in the context of what is currently passing for discussion of the war on terror.

The most common complaint about public discourse since Sept. 11 is that anyone who dares to criticize any aspect of the U.S. response is labeled anti-American. I don't dispute that. Propaganda rules in wartime. But there's another side, which is how the left has seized on what we've done wrong to dismiss the war on terrorism in toto. The left has used Bush and Ashcroft's obvious attempts to dismantle civil liberties, or idiocies like the State Department's refusal to grant a visa to the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, or the folly of invading Iraq (which is not part of the war on terrorism at all, however much the administration tries to paint it so) as proof that, once again, we cannot be morally justified in defending ourselves.

Thus, as Christopher Hitchens pointed out in a recent Salon interview, these critics equate Ashcroft's attempts to hold secret trials of captured Taliban fighters with the atrocity of the terrorist attacks. Recently, in the Village Voice, Richard Goldstein wrote that progressives who are in favor of the war against terrorism ("neo-hawks" in Goldstein's newly minted locution -- catchy isn't it? -- a category apparently broad enough to contain Hitchens, Greil Marcus, Dan Savage and Ron Rosenbaum) fail to realize that the menace of an America that vows to track down the people who are determined to destroy us should be considered "as ominous as the threat posed by terrorists."

Really? Even assuming that the shrinking economy and the expanding cost of fighting al-Qaida eat away at funding for education, healthcare and the environment, and even if we make the mistake of thinking that attacking Iraq will protect U.S. citizens, how will an economically pinched, conservatively governed America really be "as ominous" a threat (and to whom?) as terrorists willing to die to perpetrate mass killings as big as or bigger than those of Sept. 11 -- or for that matter, a ongoing series of smaller attacks?

You see this inability to weigh distinctions on the left in those who compare the war in Afghanistan and the ongoing fight against al-Qaida to Vietnam or Reagan's incursions into Central America. Or, reaching further back, to the slaughter of the Native Americans. The message is that American culture -- Western culture as a whole -- is rotten. I say Taliban, they say Crusades. I say al-Qaida, they say the Inquisition.

The most insidious form of current antiwar rhetoric can be found in the arguments that begin along the lines of "Yes, Sept. 11 was a tragedy and a crime but ..." But what? How can there be any qualifier to the murder of nearly 3,000 of your fellow citizens? I understand that those words indicate a wish to be smart and not indiscriminately brutal in our response. But what is lacking is a sense of outrage, any acknowledgment of the ugly reality that being attacked demands a response and any understanding that we are still in danger (and maybe more so now than at any time since Sept. 11, with Osama bin Laden apparently still alive and al-Qaida reconstituting itself).

Goldstein and his ilk do not deny Hitchens' characterization of Islamic militants as fascists, or the danger we are now in. But he is living in a fantasy land if he thinks that terrorists are open to "a sound moral case for standing down." Anyone who thinks that brutalists operating from a medieval mindset can be persuaded by diplomacy is fooling himself. Some people understand only force. As Lee Harris argued in a stunning piece called "Al Qaeda's Fantasy Ideology" in the August/September issue of "Policy Review," there is something pitifully beside the point in cautioning against dehumanizing people who have already dehumanized themselves. And they have dehumanized themselves, he argues, by making themselves figures in a fantasy of holy war.

Here it seems appropriate to quote Paul Fussell from his book "Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War." Fussell writes, "It was a war and nothing else, and thus stupid and sadistic, a war, as Cyril Connelly said, 'of which we are all ashamed ... a war ... which lowers the standard of thinking and feeling ... which is as obsolete as drawing and quartering'; further, a war opposed to 'every reasonable conception of what life is for, every ambition of the mind or delight of the senses' ... It takes some honesty, even if that honesty arises from despair, to perceive that some events, being inhuman, have no human meaning." Fussell fought in World War II and considers it justified and necessary. He doesn't ever say that it was ennobling. His is exactly the sort of honesty that seems beyond the comprehension of the current antiwar left.

And yet how can the left not be for this war? The goals of Islamic militancy, and the reality in many of the countries where shariah (Islamic law) rules, show a world that is the essence of everything the left should despise. In fact, it's everything the left does despise when the same values are touted, in much, much milder form, by the American Christian right.

In the current Village Voice, Thulani Davis has a piece about the Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasrin, who has been under a fatwa since 1994. Her crime? Protesting the persecution and torture of women in Bangladesh -- for example, a teenage Muslim girl killed after being lashed 101 times for having sex with a Hindu boy, a divorced woman stoned and her parents flayed after she remarried, a woman burned at the stake for adultery, the burning of schools that teach girls, medical care denied to pregnant women. Earlier this year the press reported that Saudi girls escaping from a school fire were sent back into the burning building by clerics because they were not properly covered. As a matter of everyday practice, women in Saudi Arabia have to keep covered in public, cannot drive, cannot practice any profession that brings them into contact with men.

And this is just the persecution of women. Add to it the persecution of homosexuals, and the oppression of a theocratic state that denies freedom of the press and of scientific inquiry (this in a culture with a rich heritage of scientific and mathematic discovery). In her (altogether too chipper) "Islam: A Short History," Karen Armstrong details how Islam envisions no secular social realm, that the Muslim idea of religion was inseparable from the idea of community. Bernard Lewis, an eminent scholar of Arab culture, notes that Islam contains nothing akin to the imperative in Matthew 22:21 "Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's; and unto God the things which are God's."

So how is it that, to much of the American left, a Christian fundamentalist who wants to get Darwin out of the schools is the devil incarnate, but a society in which the concept of the separation of church and state doesn't even exist is merely another culture that we must not judge? In a recent New York Times column, Nicholas D. Kristof dared to suggest that Saudi women who scorn the idea that they are repressed are wrong. The extraordinary letters he received chastised him for daring to "criticize behavior of others according to their cultural traditions." The most amazing of the lot said, "If every woman in America feels trapped in a body that she doesn't feel is good enough to be on display, are we really free?" It took me a minute to absorb what I was reading: a feminist defense, based on the theory of self-esteem, of a culture that persecutes women. This is the idiotic voice of someone who has left judgment and common sense behind. And it's the type of nonthinking that explains why Fallaci rails against "those supposed liberals who profane and desecrate the meaning of the word liberalism."

The thrill of "The Rage and the Pride" is that Fallaci is having none of it. "By God!" Fallaci writes (in her sometimes shakily self-translated English): "Don't you see that all these Osama Bin Ladens consider themselves authorized to kill you and your children because you drink alcohol, because you don't grow the long beard and refuse the chador or the burkah, because you go to the theater and to the movies, because you love music and sing a song, because you dance and watch television, because you wear the miniskirt or the shorts, because on the beach and by the swimming pool you sunbathe almost naked or naked, because you make love when you want with whom you want, or because you don't believe in God?"

Look at the smallness, the ordinariness of the things that Fallaci lists there. This is a concept of sinfulness that surpasses anything the Christian right has dared propose since the days of Calvinism. For all of her extremism, all of her bigotry, it is a threat of which Fallaci seems to have taken the full measure. And I confess to being stirred by the self-dramatization with which she places herself on the barricades. "What logic is there in respecting those who do not respect us? What dignity is there in defending their culture or supposed culture when they show contempt for ours?"

The two taboos that Fallaci goes after here are the taboo of one culture presuming to criticize another, and the deeper taboo of criticizing a religion.

The first seems to me ridiculously easy to dismiss. Does respecting another culture's traditions and customs mean excusing barbarism, like those who defend clitoridectomy on the basis that it is a cultural practice? Doesn't any culture, any person, any system of beliefs, first have to earn respect before it can be respected?

The taboo against religion is tougher because it joins leftist political correctness with the right's veneration of religion. The fawning respect paid to religious practices is by no means limited to extreme fundamentalist Islam; it has been widely on view as child sexual abuse scandals have racked the Catholic Church. Nearly every commentator takes pains to say something like "We must remember that all priests are not child abusers." Of course they aren't, but that shouldn't keep us from asking the deeper question: What is there in either the practices or the administration of the church that fosters child sexual abuse?

One of the most sickening things to me in the week after of Sept. 11 was the sudden realization that the mosque several blocks from my home was no longer broadcasting the daily calls to prayer. I understood the fear behind that, and hated that my Muslim neighbors felt they must, to some extent, make themselves invisible. And it's to America's credit that a country so prone to violence failed, with scattered barbaric exceptions and the occasional outburst of suspicious stupidity (like the woman whose call to the police resulted in those three medical students being stopped in Florida), to turn on Muslim Americans. Bush's constant imprecations against violence in those weeks must get credit for some of that.

Of course the vast majority of Muslims are not terrorists. Of course they are pained and sickened by the denigration of their faith. And of course the desire of radical Islam to stop the clock and disengage from the world is a betrayal of a heritage that Bernard Lewis writes was "for many centuries ... in the forefront of human civilization and achievement." But that still leaves the question of why Islam today leads all other faiths in religiously motivated terrorism.

No one can deny that the reasons for that are complicated. Partly they lie in Islam's lack of separation between religion and community, partly in the religion's roots in a semi-nomadic tribal culture. And much of it is, I think, a modern phenomenon, a response to the overwhelming poverty of the Middle East, some of which can be blamed, in some countries, on the prohibition against women working and the fundamentalist wish to sever ties with the rest of the world.

In such states -- and I realize that this does not describe all Muslim countries -- where there is a booming population of young people who cannot find jobs, the United States is a convenient target, especially when a government wants to deflect criticism from itself. (Those who claim that America wants to keep the Middle East in poverty never address the question of why corporate America would want to cut itself off from a potentially huge market.) Yes, as Thomas Friedman points out, in the 1950s Korea and many Arab states had the same per capita income. The economy of that smaller country now surpasses all Arab economies.

Nevertheless, even to imply a criticism of Islam is to get yourself labeled a Muslim-basher. Martin Amis recently made the perfectly reasonable observation that the way Islam treats women seems to have a lot to do with male insecurity. This was enough to get him called a bigot in London's Evening Standard by that pious high Tory A.N. Wilson, who wrote that only the faithful could make sense out of sacred texts.

It seems clear to me that if we are going to talk honestly about the war on terrorism, which Taslima Nasrin has said is not about East vs. West but about "fundamentalism and secularism, tradition and innovation," we are going to have to be able to talk honestly about religion -- all religion. Think of the rage elicited when a panel of judges ruled (correctly) that the "under God" clause in the Pledge of Allegiance was unconstitutional. Nobody bothered to add that when we're fighting an enemy who seeks to make religious law the only law, those judges were acting patriotically, making a distinction that should and must be made.

Maybe it takes a foreigner to be able to say what Fallaci says here about American culture. To affirm that, for all its stupidity, all of the shameful foreign policy we have indulged in, there has never been a more benevolent superpower than America, that we assimilate more cultures than any other country, that no system besides democracy has ever offered its citizens comparable freedom. It seems ridiculous that in the face of an enemy who has vowed to destroy us, our culture, everything and everyone familiar and loved, that affirming our belief that this is a culture worth preserving is enough to get someone labeled a bigot, an ugly American, a warmonger.

But Fallaci is revivifying and stirring when she claims that we are facing the greatest threat we have faced since fascism and Stalinist communism. However, because we are fighting an enemy who does not, as Lee Harris wrote in Policy Review, proceed from any accepted concept of military strategy but from the grip of religious fantasy, the danger we face may be greater.

So it's dishonest for me to deny that I am moved by Fallaci's call to the barricades. In one passage she promises that, were any of the landmarks of Western culture destroyed, "it is I who would become a holy-warrior. It is I who would become a murderer. So listen to me, you followers of a God who preaches an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. I was born in the war. I grew up in the war. About war I know a lot and believe me: I have more balls than your kamikazes who find the courage to die only when dying means killing thousands of people. Babies included. War you wanted, war you want? As far as I am concerned, war is and war will be. Until the last breath."

This is not writing that will last. It will never achieve the reasoned clarity that makes it still possible for us to read Orwell's war commentaries or the dispatches of Ernie Pyle, Edward R. Murrow and A.J. Liebling. But Fallaci has at least recognized that we are now facing a threat no less "opposed to 'every reasonable conception of what life is for, every ambition of the mind or delight of the senses'" than the one those men faced in World War II.

She casts the same gauntlet thrown down by a young man in Washington shortly after the attacks. The New Republic reported that, before the United States had made any military response to Sept. 11, this young man encountered a group protesting U.S. plans to attack Afghanistan and asked them, "Why don't you just kill yourselves?" When a cop upbraided him, he responded, "My brother was killed in New York. And these fuckers ..." Then he stormed off in disgust. This is the question Fallaci puts to those who feel the United States got what was coming to it, or that we cannot justifiably respond to Sept. 11 and other terrorist attacks on our people: She's asking, Do you want to kill yourselves? Suicide, she is saying, is the outcome of a failure to name the threat and to meet it.

Shares