Edmund Wilson's 1945 New Yorker essay "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?" (the title referred to Agatha Christie's 1926 novel "The Murder of Roger Ackroyd") more or less demolished the "classical" country-house murder mysteries of Christie and her school. The series detective novel took its place, and today it rules the realm of crime fiction. These books provide pleasure to many loyal fans, which is all to the good. What's not so good is the inflated critical reputation of the better writers, and of the genre as a whole. The American detective novel may be commercially viable, but it is devoid of creative or artistic interest.

It took me a long time to realize this. I got started in this genre in 1969, after reading Eudora Welty's rave review of Ross Macdonald's "The Goodbye Look" on the front page of the New York Times Book Review. I got my parents to drive me to the library, where I took out the novel. I found myself in agreement with Welty, and went on to read nearly all of the rest of Macdonald's novels, which featured and were narrated by private detective Lew Archer. The books worked on multiple levels. As I learned when I later read the greatest worker in this field, Raymond Chandler -- who was at his artistic peak at the time of the Wilson essay -- Macdonald kept the sense of the private eye as a flawed knight patrolling the mean streets, but toned down the emotional volume and the verbal extravagance: Chandler averages one simile a paragraph, Macdonald one a chapter. What the latter writer offered, more than his literary mentor, was, first, coherent plots; second, an almost journalistic interest in the social and economic strata of contemporary Los Angeles; and, third, a consistent and compelling theme: the power of the past to influence the present.

I can't prove this, but it seems to me that the Welty review started a trend: taking a detective writer and anointing him or her as not just a pulp writer (not just a Mickey Spillane) but a purveyor of literature (a Chandler). Such claims were made every year or two, and I dutifully tried each one out. I think the first was Robert Parker. His Spenser books -- I read three or four of them -- were pleasant enough. But they weren't in Macdonald's ballpark, and not in Chandler's sports complex. Some of the observation of behavior and relationships was OK, but what I seem to remember most was a lot of posturing. I went on to the next writer. And then -- like Charlie Brown kicking the football -- to the next.

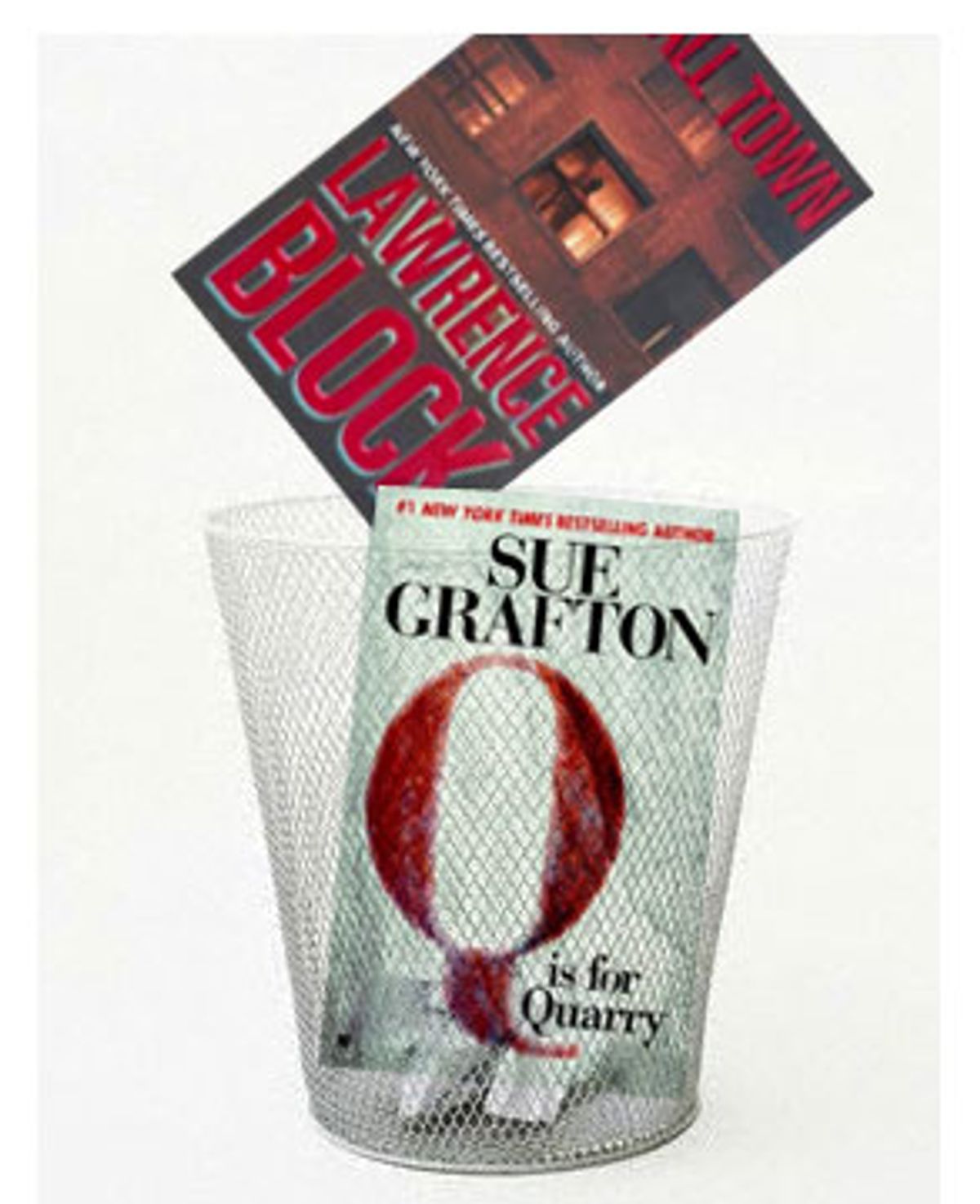

Each time I'd prowl bookstores and libraries and pick the detective books with the best blurbs. And some have amazing blurbs -- five or six pages of them in the front of the paperbacks, declaring that the book is brilliant or unforgettable or a classic. Sometimes I'd have a slip of paper in my wallet with a recommendation from Janet Maslin, who's inherited Christopher Lehmann-Haupt's habit of devoting a few New York Times columns a year to surveying the best of the best detective novels. In this way I made my way through Sue Grafton, Elmore Leonard, James Lee Burke, Lawrence Block, Tony Hillerman, Jonathan Kellerman and a half-dozen others. Sometimes, as in Leonard's case, I truly admired the writer's skill. (I list him as a series writer even though his lead characters have different names. But they are the same guy.) But whether I stayed with the writer for two or three books (Block and Kellerman, who with his sympathetic child shrink, Alex Delaware, follows Macdonald just as Macdonald followed Chandler) or barely was able to finish the first, I always ended up disappointed.

The problem, I came to realize, is that all detective series seem to require two items that run counter to literary values and that, no matter what the author's skills (clean prose, social or psychological observation, plot construction), will artistically doom it. The first is the main character, who is invariably romanticized or sentimentalized and who is always a combination of three not especially interesting things: toughness, efficacy and sensitivity. (When the writer resists applying any or all of these traits, the character ends up being bland.) The second is the very formulaic quality that lets a book be part of a series. Similar things happen in similar ways, which is probably as apt a definition as you'll ever find of how not to make good literature. Chandler -- not to mention Arthur Conan Doyle -- got away with it because he was a genius and an original, Macdonald because he was gifted and started early in the day. Their successors have no such luck.

I've generally been able to resist football-kicking lately, but earlier this year, I was in an airport with nothing to read. So I bought the book with the best blurbs -- "City of Bones" by Michael Connelly, whom Maslin had recently hailed. For another long plane ride a bit later, I picked up S.J. Rozan's "Winter and Night," on the cover of which was a quote from Dennis Lehane: "To read S.J. Rozan is to experience the kind of pure pleasure only a master can deliver." Inside I found the following from another much-praised writer, Robert Crais: "S.J. Rozan paints with the full palette of the human heart, using depth, detail and nuance of character that I haven't seen since Raymond Chandler. (Yes, I mean it.)" One thing that characterizes the current valorized crop -- which also includes George P. Pelecanos and Harlan Coben -- is a lot of logrolling in the blurb department.

It turned out that the admiration for these books went beyond blurbs. Unbeknownst to me, "Winter and Night" had already won the Edgar Award (given by the Mystery Writers of America) as the year's best novel. Then, this past fall, at the Bouchercon convention for fans, writers and editors of mystery books, "City of Bones" won both the Anthony and the Barry awards as best novel of the year, and "Winter and Night" won the Macavity Award for best mystery novel.

These two books' sweep of the accolades seals the case. To start with "City of Bones," the best way I can characterize it is with an oxymoron: amazingly ordinary. The detective, Hieronymus "Harry" Bosch of the Los Angeles Police Department, is a knight of the Chandler-Macdonald school, without any notable individuality or insight. He tries to do the right thing, despite roadblocks of various kinds in his path. In a perfunctory way, he gets the girl, despite being twice her age. He solves the mystery, which turns out to be neither surprising nor interesting. The girl dies, gratuitously. Harry broods over that, and also whether to quit the LAPD because it is a dehumanizing bureaucracy. He does. End of book. It was a competent piece of craft and a painless enough way to kill a few hours, but nothing more.

Connelly has since published another Bosch book, "Lost Light," and the first few sentences of the (glowing) Publishers Weekly review tell me all I need to know: "Even though this marks the ninth outing for Harry, the principled, incorruptible investigator shows little sign of slowing in his unrelenting pursuit of justice for all. Disillusioned by his constant battle with police hypocrisy and bureaucracy, Harry quits the department after 28 years on the job. Like so many ex-cops before him, he finds retirement boring: 'I was staying up late, staring at the walls and drinking too much red wine.' He decides to take advantage of his newly minted private-eye license and get back to work."

"Winter and Night" turned out to be as negligible as "City of Bones," but more annoying. Although the setting is New York rather than L.A., and the main character a classical-piano-playing private eye (Bill Smith) rather than a cop with a saxophone, it's driven by the same warmed-over angst: It's just that Rozan's pathetic fallacy involves cold overcast days instead of Connelly's smog and Santa Ana winds. (The Boston Globe called the book "very well-written, displaying Rozan's ability to describe place and weather." I don't know about you, but I'm always in the market for a good weather novel.) The book is overlong (388 small-print pages), overwritten and overly dependent on the convention of moving the plot by means of cellphone calls, and on bits of business involving preparing and drinking coffee and lighting and smoking cigarettes.

Unusually for this genre, the novel, much of which is set in the all- or mostly male worlds of high school football teams and police departments, has an agenda, or at least a thesis, having to do with the burden of violence that all men must confront and deal with. This is at least arguable, but Rozan, who is female, has no clue how males talk among themselves. She seems to have gotten her ideas about this from observing the conversations of 10-year-old boys. That is, her guys swear at roughly the rate of every fourth word and always address each other by their last names.

Here's what one character says after Smith points out the Harvard diploma on his wall:

"Harvard fucking Law. Rutgers undergrad, where I worked my fucking ass off to get into fucking Harvard. Because I was going to goddamn be somebody, Smith."

We can be thankful that Chandler and Macdonald are not alive to read that nonsense. I am, however, and it has strengthened my current resolution that even if the blurbs glow with the intensity of the midday sun, I am off these books for good.

Shares