In the ecosystem of modern comic books, funny animals are the endangered species. Superheroes still make up most of the population, but thanks to the rise of "literary" graphic novels, creatures of different colors -- war correspondents, lovelorn slackers and self-obsessed cartoonists -- roam alongside the men and women in tights. But the art form's increased respectability undercuts some of its youthful fun. Whole menageries of talking critters -- screw-loose squirrels, lucky ducks, li'l devils, amorphous shmoos -- are going extinct.

Overall the old funny-animal comics make no great loss, having mostly been cheap knockoffs of Disney properties or Saturday morning TV characters. But some ingenious creations did spring onto the scene, like Carl Barks' classic Donald Duck comics and R. Crumb's ribald adventures of Fritz the Cat. Two lesser-known yet landmark titles -- one accessible to all readers, the other forbidding and definitely not for kids -- have unfolded in recent years in extended but self-contained, novelistic story lines, and will conclude within months of each other. Dave Sim's "Cerebus" finished its staggering 6,000-page, 300-issue publication in March, while Jeff Smith's "Bone" completes its more modest but still impressive 55-issue run this month.

Jeff Smith's Bone cousins don't look like bones, but rather like half-pint, pie-faced humanoids -- distant kin to Walt Kelly's Pogo the Possum or Casper the Friendly Ghost, perhaps. And Dave Sim's Cerebus should not be confused with Cerberus, Hades' three-headed guard dog in Greek mythology. Instead, "Cerebus" chronicles the exploits of a talking aardvark who drinks heavily and has a penchant for violence, one-liners and messianic tendencies.

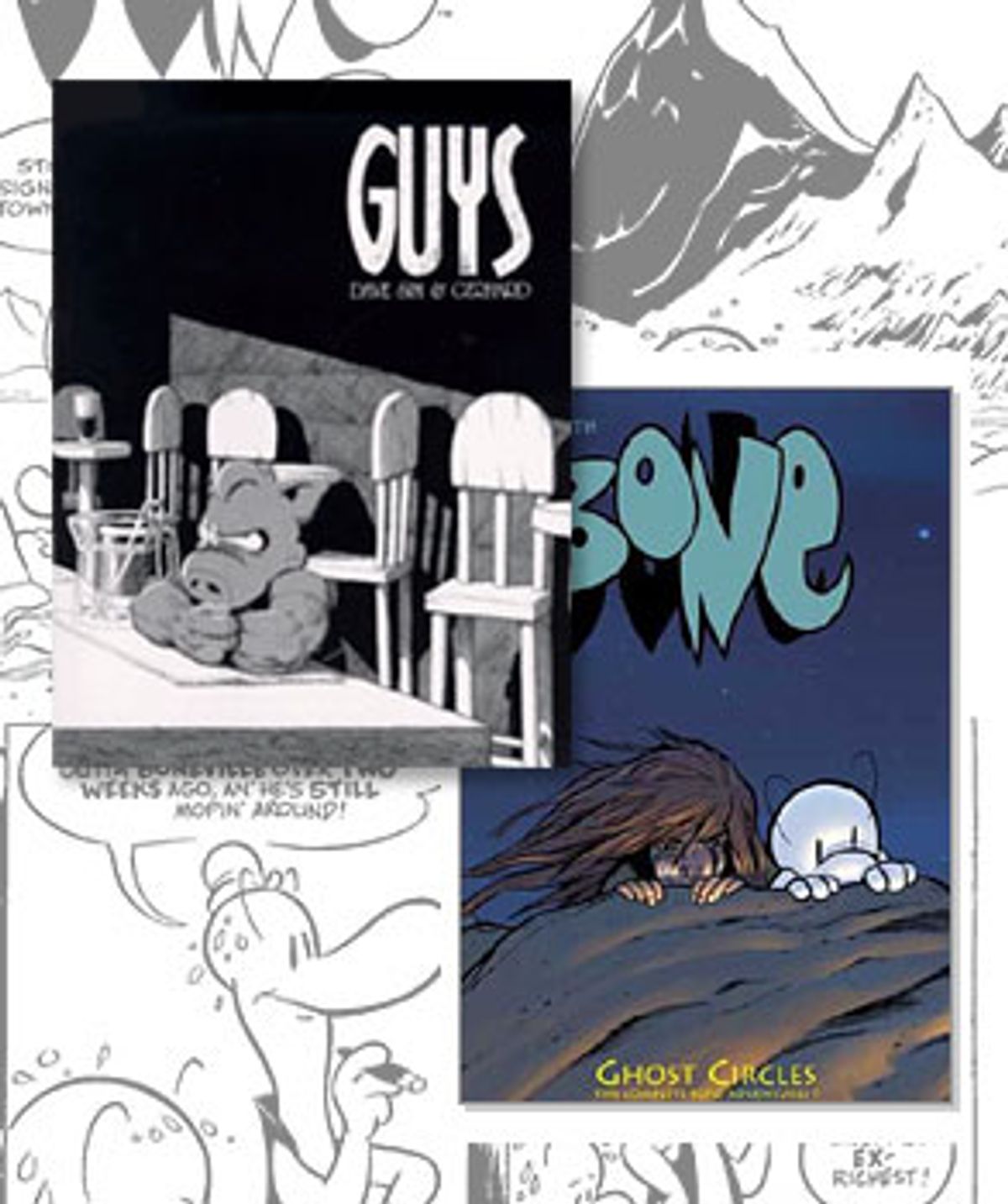

"Bone" and "Cerebus" share superficial similarities. They're both drawn in black-and-white and self-published by their creators. In both, quirky, anthropomorphic beings shed light on mankind's foibles and virtues. Both books extend their lives outside the comic shops through hefty, trade-paperback reprint volumes available at bookstore super chains. The 16th and last "Cerebus" collection, "The Last Day," chronicles the aardvark's final hours and publishes this month, while Smith will sandwich all 1,300 pages of "Bone" between two covers in a volume due to publish in July.

But beneath the surface, "Bone" and "Cerebus" prove to be so different, they're almost like photographic negatives of each other. "Bone" celebrates optimism and narrative simplicity, while "Cerebus" embraces cynicism and experimentation worthy of a mad scientist. Sim and Smith started as comrades in arms, yet their relationship soured into one of the industry's strangest feuds. "Bone" and "Cerebus" mark opposite ends of the comic-book spectrum in tone and complexity. Their heroes aren't technically human, but you can place virtually all modern graphic novels somewhere between them.

Smith's "Bone" may be the most friendly and engaging comic book of the past decade. Since 1991, Smith has written and drawn the adventures of the three Bone cousins: good-hearted mensch Fone Bone, happy-go-lucky goofball Smiley Bone and greedy, hot-headed Phoncible P. "Phoney" Bone, who needs constant rescuing when his get-rich-quick schemes go awry. The "Bone" saga begins with the trio fleeing their never-seen home of Boneville and discovering "a deep, forested valley filled with wonderful, terrifying creatures." Recurring characters include an enigmatic, cheroot-chomping red dragon; a farm girl named Thorn who becomes Fone Bone's unrequited love; and ravenous, none-too-bright Rat Creatures, the book's answer to Wile E. Coyote. Fone Bone's exclamation "Stupid, stupid rat creatures!" became a comic shop catchphrase.

Throughout "Bone," Smith demonstrates a graceful command of unappreciated comic-book styles. The early issues include scary chases as dynamic as anything drawn by action-obsessed artists like Frank Miller (of "The Dark Knight"), but prove essentially comic and sunny. Smith's sharp characterizations and clean drawing style reflects his love of the "Pogo" and "Peanuts" strips and especially Barks' "Donald Duck" tales, which took the Donald and his zillionaire uncle, Scrooge McDuck, on adventurous treasure hunts in exotic locales. Even the name Fone Bone pays homage to the late Don Martin, penciler of Mad magazine's most outlandishly elastic cartoons.

"Bone" began as a fantastical, freewheeling romp -- one of the first extended story lines depicted "The Great Cow Race" -- but it gradually yet seamlessly turned into a dark, sprawling fantasy epic. Recent issues have found the Bones on the wrong end of a massive siege akin to the Helm's Deep sequence of "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers." The Bones and Thorn learn that she's not only the heir to a fallen kingdom, but possibly the decisive figure in an apocalyptic battle between good and evil. In Tolkien terms, she's like Frodo and Aragorn wrapped up in one.

"Bone" is also more sophisticated than it first appears. In the story arc "Rock Jaw: Master of the Eastern Border," Smiley and Fone Bone protect a bunch of cute woodland creatures from the title character, who resembles a big cat from Disney's animated "Jungle Book." Yet Rock Jaw has not just wicked claws, but also a Manichean worldview that sets off a debate over the purpose of life -- in between bona fide cliffhangers. In the "Ghost Circles" story line, evil magic turned the lush valley into a blasted wasteland, against which the Bone cousins' capacity for loyalty and humor provide the only human element.

Even when Smith pours on the mystical hoodoo a little thick, the funny but multifaceted characters keep the tale on a solid footing. More than any other current comic title, "Bone" deserves -- and could support -- the kind of popular attention that elevated Harry Potter from the rank and file of children's books. "Cerebus," on the other hand, will never be more than a cult success, since it's such an iconoclastic project -- not just in comics, but in all of mass media -- that it defies categorization. Call it "satire" by default. Dave Sim began the book in 1977 as a spoof of "Conan the Barbarian" comics that replaced the longhaired muscleman with a 3-foot, sword-swinging, talking aardvark. "Cerebus" initially made hay from the incongruity of a deadpan, self-centered "earth-pig" playing the macho hero.

But Sim had bigger ambitions for the book than anyone could imagine, and by 1979 had announced, at the age of 23, that "Cerebus" would be a self-contained story of 300 issues -- the "War and Peace" of comic books. Sim parodied modern politics by taking Cerebus from mercenary to diplomat to, in the 25-issue "novel" "High Society," the elected prime minister of a fictitious, preindustrial nation (that bears a passing resemblance to Sim's native Canada). The subsequent book "Church and State" ran twice as long (about 1,100 pages) to illustrate the abuse of religious authority as Cerebus became pope of a Catholic-style church. By the end of "Church and State," a character prophesied that in the final issue, the eponymous aardvark would "die alone, unmourned and unloved."

The artist known as Gerhard designs the book's intricate backgrounds (which look far more solid and tangible than most comic drawings) while Sim scripts the book and draws the characters. "Cerebus" shows the talent and vision to rival any of the stars of the current comic books scene, including Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman. As a restless, anything-goes stylist, Sim proves equal parts theatrical stage manager, cinematic cameraman and comedy-club impressionist. Recurring characters include ersatz versions of Groucho Marx, Mick Jagger and the Three Stooges, reinterpreted for Cerebus' milieu but with their vocal and visual traits captured with hilarious accuracy. Sim has also offered poignant, realistic portraits of late-career F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and Oscar Wilde. The 11-issue "short story" "Melmoth" juxtaposes a near-catatonic Cerebus killing time in a café with an accurate account of Wilde's last days that works as a kind of historical biography in pictures.

For literally decades, Sim's aardvark has shown a classic comedian's gift for slapstick and the slow burn. Yet "Cerebus" proves its most moving generally at the end of its extended story lines, when Cerebus receives some kind of enlightenment instead of worldly power or romantic attachment. The "earth-pig" ultimately proves more tragic than comic: No matter how many epiphanies he has, he can never significantly change his brutal, selfish nature. As a violent, charismatic and funny antihero whose pursuit of power never provides peace of mind, Cerebus resembles few other characters in contemporary pop culture so much as Tony Soprano.

In the late 1980s and early '90s, Sim became a folk hero for independent comic book artists. He spoke out for creators' ownership of their work, used "Cerebus" to boost other up-and-coming comics and even ran a 13-page excerpt of "Bone" in 1992. ("You guys are going to love this one," Sim announced.) Sim has proved resoundingly that one can write, draw and self-publish a monthly comic for 27 years -- but not necessarily that one should.

As Sim's ideas about religion and gender relations changed over time, the setting and characters of "Cerebus" became increasingly unwieldy vehicles for their creator's personal views. Sim dabbled more heavily in dense textual pieces, including mannered pastiches of Wilde and Fitzgerald's prose styles. He indulged in metafictional gambits, injecting himself into the narrative to talk directly to Cerebus. He recycled ideas and twice took Cerebus off the earth itself to travel the solar system -- which admittedly provided some of the book's most breathtaking moments.

In reading "Cerebus" over the last 10 years, it became increasingly difficult to separate the work's wild creativity from Sim's strident views about women, beliefs that Sim insists on calling "anti-feminism," while his critics -- and most of his dwindling readership -- find them indistinguishable from straight-up misogyny. Appreciating later "Cerebus" can be like trying to separate the work of, say, Richard Wagner or D.W. Griffith from their personal beliefs.

But Sim's comic book isn't -- necessarily -- as didactic as Sim himself. By far the book's most sympathetic and well-rounded role is Jaka, a princess turned dancer and Cerebus' true love (insofar as he's capable of love). With one or two exceptions, Sim's men never prove to be avatars of reason, but Machiavellian plotters, self-absorbed artists or colorful clowns. For all of Sim's polemics, "Cerebus" comes closer to the equal-opportunity misanthropy of "Gulliver's Travels" than to the elevation of one gender over another.

Since he began condemning women as emotion-based "devouring voids" and the source of a host of marital and social problems, Sim turned from champion to persona non grata in the comics field, and even had a highly public falling out with Jeff Smith. In a 1999 interview with the Comics Journal, Smith described a weekend visit from Sim, who expounded on his views about women in front of Smith's wife. "Bone's" creator claims to have said "Dave, if you don't shut up right now, I'm going to take you outside and I'm going to deck you" and that the "Cerebus" creator hastily backed down.

But a year after the interview appeared, Sim published an editorial in "Cerebus" calling Smith a liar and challenging him to a three-round boxing match to settle their differences. (Not surprisingly, the challenge coincided with the Ham Ernestway storyline in "Cerebus.") Smith opted not to box his fellow cartoonist, sent "Cerebus" a letter telling Sim to "get stuffed" and has avoided further comment on the affair. However, in the letters page of "Bone's" penultimate issue, Smith tipped his hat to Sim and Gerhard for getting to 300: "The troubles between Dave and I are personal, not professional, so congratulations, boys. You did it and you did it on time. I know it took a dedication few artists will ever have."

Though "Cerebus" tries its readers' patience in all possible ways, it remains a book that stretched the possibilities of the comic book form further than any rational person could expect. "Bone" doesn't match "Cerebus" for insane ambition, yet proves about a zillion times more satisfying -- not the least by making the devalued "cartoony" comic books seem cool again.

"Bone's" bittersweet ending inspires the kind of melancholy that accompanies the final chapter of any wonderful piece of escapism, but at least Smith expects to pen further tales in the "Bone universe" in the future. (He next plans to do a limited Captain Marvel series for DC Comics.) In interviews, Sim has said he has no immediate plans to continue with comic books at all, and likens himself to a prisoner facing the end of a 27-year sentence. "Cerebus'" conclusion may leave readers both impressed at Sim's achievement and relieved that it's over. In "Cerebus" 121, the Oscar Wilde character's capper for "Church and State" applies to the culmination of the comic book itself: "The ending was less of a grand finale than a grand finally." At least "Cerebus," like "Bone," gave funny animals a grandeur all their own.

Shares