One evening in February 1963, Dr. Ruth Tiffany Barnhouse Beuscher returned home from a long day treating psychiatric patients. Her husband, William, also a psychiatrist, was already in bed. His custom was to retire early and read the evening paper. Ruth wearily mounted the stairs and sat on the bed next to him. Without any greeting or a look in her direction, he dryly asked, "Have you heard the news about Sylvia Plath?"

"No, what is it?" she replied, sensing the news was bad.

"She's dead," he said. "She committed suicide."

He returned to reading his paper without another word. Ruth quietly stood up and went downstairs to the kitchen. She poured herself a drink and sobbed. She remained downstairs for hours, thinking about Sylvia, and furious at her husband for the brutal way he told her about Sylvia's death. He knew of Ruth's relationship with Sylvia, including their compelling attachment to each other. When I interviewed Ruth, she said her marriage had been an unhappy one for many years. But the breaking point came that night when he told her of Sylvia's death. It took her four more years to make the move, in part because of her grief over Sylvia.

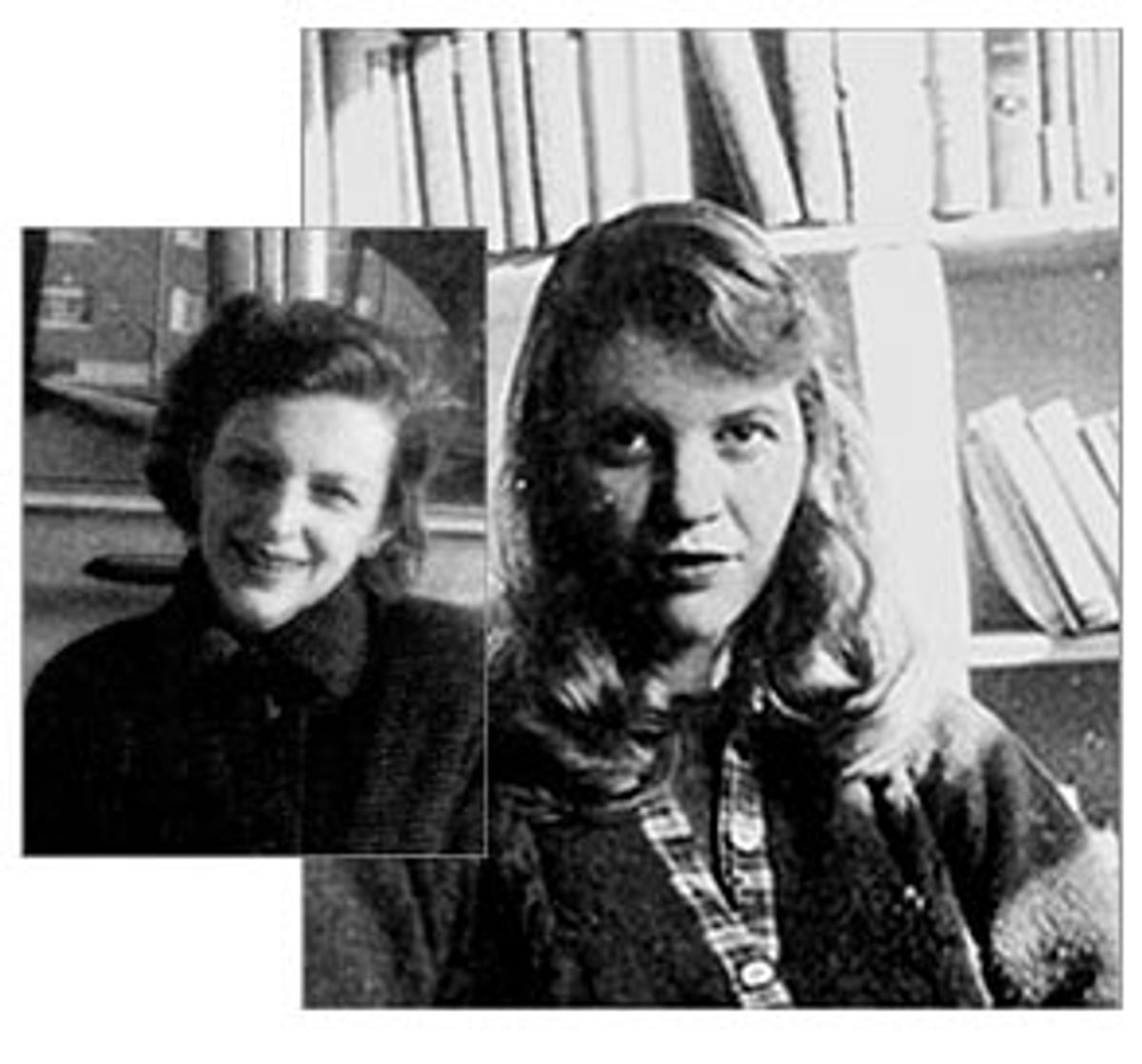

Ruth Barnhouse had been Sylvia Plath's psychiatrist since her hospitalization at McLean in 1953, a period in her life immortalized in her semi-autobiographical novel, "The Bell Jar." But most Plath observers don't realize just how close Barnhouse remained with Plath after she left McLean, and even after she left the country for her final ill-fated move to England with her husband, Ted Hughes. Plath biographer Paul Alexander is one exception. In an article for the Nation he wrote, "As I'd expected, she [Ruth Barnhouse] was a singular figure in Plath's life ... From September 1953 until February 1963 Barnhouse and Plath stayed in more or less constant contact either by mail or by telephone. During those years Plath wrote Barnhouse long, revealing letters."

Fascinated by "The Bell Jar" as an adolescent, I was part of a generation of women who felt that Sylvia Plath spoke to our desire to balance our personal ambition with close relationships, and the intense internal conflicts that produced. And as a psychoanalytic psychologist, I've written a great deal about the relationship between therapist and patient. So after having been left unsatisfied by all of the Plath biographies, I wanted to know more about what happened, and didn't happen, in Sylvia's treatment. I was primarily interested in why she did not remain in the treatment she so badly needed, yet could not give up her relationship with her psychiatrist. Had Ruth Barnhouse tried to keep Sylvia Plath in therapy, but was unable to? Or had she believed Plath had improved enough to leave her care?

I had my first, brief contact with Barnhouse when I interviewed her in 1990 for an academic paper I was working on. Then in 1998 I reconnected with her again, this time asking whether I could come and interview her about her life, especially about the long-term impact of having treated Sylvia Plath. I offered to travel from Milwaukee to Nantucket, Mass., and stay the weekend in a nearby inn if she was willing to discuss her relationship with her famous patient. She eagerly agreed to meet with me and even allow me to tape our conversations.

Plath's last journals, when she was communicating with Ruth mostly through letters, mysteriously disappeared, and her final one was destroyed after her death by Ted Hughes, who said that he never wanted their children to see it. The letters from Ruth to Sylvia, held in the Smith College library, will not be fully available to the public for decades, though a reputable source has described them as "surprisingly intimate." And Ruth Barnhouse burned the dozens of letters she received from Sylvia while she lived in England. So an interview with Ruth offered the only opportunity for real answers about their relationship.

What I learned that December weekend, on Nantucket, surprised me. Ruth was 75 years old, still intellectually sharp and possessing a great sense of humor. She was also brutally honest. Always entertaining, she used her formidable intellect to forge strong opinions on almost everything. Yet I couldn't help noticing that she was quick to provide simplistic answers to certain difficult questions, including some of my most pressing queries about Plath. In my first minutes with her, I knew I was not going to get all I had hoped for. But I stayed the weekend. I couldn't walk away from what might be my last chance to learn more about this historic relationship.

Though my interviews with Ruth Barnhouse answered some questions, they raised even more. I was left with the inescapable conclusion that this talented therapist had certain blind spots about Sylvia that may have interfered with her treatment. While it is clear these two women forged a powerful relationship that helped Sylvia Plath, they also crossed some professional boundaries along the way.

I am in no way, however, suggesting that Ruth bears any responsibility for Sylvia's death. Blame is cheap and does not do justice to the longtime internal struggle and unbearable emotional pain that characterizes any suicide. One therapist told Ruth her treatment may well have kept Sylvia alive a few extra years, and there's no reason to think that isn't true. Every therapy relationship fails in some ways, even when it succeeds grandly in others. Sylvia and Ruth were no exception.

"The Bell Jar" recounts how Plath, on Aug. 24, 1953, took a large number of pills, left a note saying she had gone for a long walk, and then hid in a crawl space underneath the kitchen. After her family found her two days later, she was taken in a semicomatose state to the hospital, and when she had recovered from her physical illness, she was transferred to McLean Psychiatric Hospital. It was there, after being diagnosed by senior psychiatrists, that Sylvia was assigned to Ruth Barnhouse for treatment.

In the "The Bell Jar," Ruth was given the name Dr. Nolan, and described as looking like "a cross between Myrna Loy and my mother. She wore a white blouse and a full skirt gathered at the waist by a wide leather belt, and stylish crescent-shaped spectacles." So she reminded her of a movie star. On Ruth's part, she said she liked Sylvia immediately, that they clicked. She told me in our earlier phone interview, in 1990, that they considered themselves two of a kind: Both were child prodigies with high IQs; both were ambitious and determined; both considered themselves "intellectual snobs."

Sylvia, though, didn't know she was being treated by a novice therapist. Ruth was a psychiatric resident, with very little experience in psychotherapy, when she was assigned to treat Sylvia Plath. Ruth told me, "Sylvia was one of my first patients at McLean."

Now, while Sylvia had little money, she did have status. She had a wealthy mentor in writer Olive Prouty, who arrived at the hospital in her black Cadillac, promising to pay for Sylvia's treatment. Sylvia was no poor patient stuck on a back ward. But, as Ruth told me in 1990, McLean was, first and foremost, a teaching hospital, and it was not unusual for the high-status patients to be assigned residents. Also, Ruth was 30 years old and Sylvia only 19. Perhaps the hospital's graybeards thought a young resident might bond more easily with their young patient.

But why would Prouty and Aurelia Plath, Sylvia's mother, allow Sylvia to be treated by a trainee? When I asked Ruth this, she responded, "I don't think they knew I was that inexperienced. It was McLean and I was the doctor assigned to her. That was it."

Furthermore, while the body of Sylvia Plath literature refers to Ruth Barnhouse as her "analyst" or "psychoanalyst," she was not a psychoanalyst. She received psychoanalytically oriented training and supervision during her residency at McLean, but did not go through analytic training. She was in therapy during medical school with an analyst in training, but told me that "at least a third of the time I didn't show up. I don't think I ever really got into it." Later, when she experienced marital difficulties, she said she went through analysis, and that it was helpful. But during the two periods of time when Ruth treated Sylvia, she had not yet had her own treatment. Back then, in the heyday of psychoanalysis, personal experience with therapy would have been considered essential for managing Sylvia's primitive feelings and the emotions she would trigger in Ruth.

Was Ruth daunted at the prospect of taking responsibility for treating such a seriously ill patient? Characteristically, she said, "Not at all. It never occurred to me to think that I couldn't treat her. I knew I could." Ruth's neophyte bravado may well have been both the source of her immediate therapeutic success with Sylvia, and also the reason she underestimated the extent of her illness.

Ruth Barnhouse was a very self-confident woman, and I have no doubt that she was a precocious, strong-willed young psychiatrist. When she observed how upset Sylvia became after having visitors, Ruth did not hesitate to ban all visitations until further notice. This naturally angered both Prouty and Aurelia Plath, both of whom felt they had a right to see her regularly and monitor her treatment. They felt Ruth was turning Sylvia against them, and soon made plans to transfer her to another hospital.

They changed their minds, reluctantly, when the hospital staff convinced them that Sylvia's condition had improved under Ruth's care. But the wounded Prouty did say she would no longer pay for Sylvia's treatment after January. No doubt there was pressure, spoken or unspoken, to "cure" Sylvia by the end of the year.

Eventually the staff, including Ruth, decided that the time had come to try shock therapy, even though Sylvia had been traumatized by shock treatments in her previous therapy. Sylvia was frightened, but agreed to shock treatment because of her trust in Ruth. In mid-December, after only a few treatments, she "miraculously" recovered from her depression. As Sylvia describes it in "The Bell Jar": "All the heat and fear purged itself. I felt surprisingly at peace. The Bell Jar hung suspended, a few feet above my head. I was open to the circulating air."

Ruth told me she had never seen anything like it, and suspected Sylvia had gotten better because Ruth told her she would. In an earlier interview with Plath biographer Alexander, Ruth speculated that the shock treatment might have satisfied some need in Sylvia to be punished, and in a Jan. 3, 1959, journal entry, at which time she had resumed treatment with Ruth on an outpatient basis, Sylvia herself says: "Why, after the 'amazingly short' three or so shock treatments did I rocket uphill? Why did I feel I needed to be punished, to punish myself? Why do I feel now I should be guilty, unhappy: and feel guilty if I'm not? Why do I feel immediately happy after talking to RB [Ruth Barnhouse]? Able to enjoy every little thing ..."

Clearly, there was something uniquely therapeutic for Sylvia in Ruth's presence. So why didn't she remain in the therapy that she so desperately needed?

As Alexander wrote: "By January 13, McLean officials, who had begun treating Sylvia without charge, decided that her recovery was so remarkable that she did not need to stay in the hospital. They concluded -- amazingly -- that she was ready to return to Smith as a special student."

I asked Ruth if she and Sylvia talked about her remaining in outpatient treatment with her in Boston, rather than returning to Smith. Surprised by my question, she told me that Sylvia received some follow-up counseling at Smith. Ruth said it was unthinkable that she not complete her studies there.

Sylvia successfully completed her degree, graduating with honors. But most people do not know that Sylvia continued to see Ruth whenever she came to Boston, which was at least monthly -- enough to keep her going, but not enough to make progress. Ruth said she never attempted to keep Sylvia in treatment with her, always encouraging her to move out in the world and be as independent as possible. I asked Ruth if she encouraged Sylvia to get regular treatment in Northampton, Mass. "Yes, I did. But she didn't want to see anyone else. She didn't like the psychiatrists attached to Smith ... She found this person she liked, and that turned out to be me."

Sylvia wanted to study in Europe and Ruth supported her application for a Fulbright scholarship. In Ruth's letter to the review committee she assured them that Sylvia was stable enough to go to England, in spite of her psychiatric history. Without her symbiotic relationship with her mother and her transference to Ruth, she furtively searched for male companions. She arrived in England in mid-September and immediately pursued several different men. When nothing came of these relationships, she developed physical and emotional symptoms by year end. Suffering with a bad sinus infection and having visited a psychiatrist by January, she met Ted Hughes in February. Her intense attachment to him was instantaneous and obsessive. Sylvia was not the independent woman that she and Ruth wanted her to be.

I asked Ruth if she really believed Sylvia was strong enough to go to England. She said, "How could she not pursue a Fulbright? And how could I stand in the way of her doing that?" She felt that far too many people tried to control Sylvia. Everyone had an idea about who and what she should be. "I was bending over backwards not to take a piece of her."

Ruth's identification with Sylvia gave her an edge. Sylvia opened up to her as she did to no one else. But sharing her premature, pseudo-independence; sharing her flight into marriage as an escape from parental domination; sharing the experience of becoming pregnant shortly into a bad marriage; and sharing her fear of engulfment when anyone got too close -- perhaps these things clouded Ruth's judgment about what Sylvia needed.

Sylvia's second period of treatment with Ruth was in 1958-59 after she married Ted and subsequently returned to America. Sylvia began therapy in secret, due to her family's disapproval of Ruth, and could only pay a portion of the usual fee. The weekly sessions appeared to be going well, and Sylvia was feeling much better. But the therapeutic relationship was not without its problems. In a journal entry dated Dec. 17, 1958, Sylvia writes: "Angry at R.B. for changing appointment tomorrow. Shall I tell her? Makes me feel she does it because I am not paying money. She does it and is symbolically withholding herself, breaking a 'promise,' like Mother not loving me, breaking her 'promise' of being a loving mother each time I speak to her or talk to her. That she shifts me about because she knows I'll agree nicely & take it, and that it implies I can be conveniently manipulated. A sense of my insecurity with her accentuated by floating, changeable hours and places. The question is: Is she trying to do this, or aware of how I might feel about it, or simply practically arranging appointments?"

When I asked Ruth if Sylvia's journal report was accurate, she said yes. She made no apologies, simply saying that she made time for patients as needed, and wouldn't "kick someone out of the office if she was crying." If she needed to rearrange her day, that was her prerogative. She seemed oblivious to the therapeutic standard of consistency as a way of providing a safe environment for the patient. Sylvia's questioning of Ruth's motivations seemed quite astute to me. Was Ruth aware of the consequences of her behavior, I wondered?

Trying to figure out what her motivations might have been, I asked if she had been ambivalent about seeing Sylvia, or resentful about her not paying. She said, "Not at all. I enjoyed seeing her." When I asked Ruth how she felt about Sylvia, she reluctantly admitted that she loved her. And it appears that the feelings were mutual. Sylvia wrote admiringly about Ruth in her journal, noting how much she looked forward to seeing her. She writes, "I believe in R.B. because she is a clever woman who knows her business & I admire her. She is for me a permissive mother figure, I can tell her anything, and she won't turn a hair or scold or withhold her listening, which is a pleasant substitute for love." It appears that Sylvia either didn't realize, or couldn't bear to admit, that Ruth actually loved her.

What distinguishes a psychoanalytic treatment from other forms of therapy is that the patient forms an attachment with the analyst, then "transfers" early fears, longings, anger and other feelings onto her, and this transference is analyzed. This takes the form of the analyst exploring the patient's feelings toward her. This apparently did not occur in Sylvia's treatment. So I asked Ruth: "Did you encourage Sylvia to talk about her feelings toward you?" Surprisingly, she said that she did not. She focused on Sylvia's feelings about her mother, Ted and other important people in her life.

Clearly, Ruth was not comfortable being the object of Sylvia's intense feelings. Ruth gave Sylvia permission to hate her mother but not permission to express either love or hate toward her. Sylvia's self-report suggests that neither was comfortable talking about their relationship -- "am very ashamed to tell her of immediate jealousies; the result of my extraprofessional fondness for her, which has inhibited me."

Had Sylvia stayed in treatment longer, perhaps they would have eventually gotten there. But Sylvia and Ted decided in January 1959 to return to England by the end of the year, though Sylvia was still very much involved in her sessions with Ruth. Ruth told me that she thought Ted had pressured her to go. I asked her if she had ever met Ted, and she said, "Oh, yes. I had tea with them at their apartment."

"During the treatment?" I asked.

She said yes, that this had occurred several times. I asked if she had concerns about seeing Sylvia outside of the office. "No, it was only tea," she said and admitted she was curious about Ted and wanted to meet him. Initially, she found him charming and handsome, as Sylvia had. But, over time, she came to dislike him intensely and felt that Sylvia had made a bad choice.

I again asked if she had reservations about Sylvia moving back to England. Not only was her therapy incomplete, but she was about to leave the country with a man Ruth believed was not a good person or husband. She reiterated that it was not her place to question Sylvia's decisions. "Besides," she said, "she was pregnant by that time." On Feb. 28, 1958, a month after making the decision, Sylvia wrote in her journal, "Nightmare before going to R.B. this week: train broke down in subway in a fire of blue sparks, got on wrong track, driving in old car with Ted, drove into deep snowdrift and the car fell apart, struggled to a telephone after 11, her maid answered, and I felt she was home, either knowing this would happen and thus not coming out, or pretending she wasn't home. Relived with all the emotion the episode at the hospital in Carlisle. Murderous emotions in a child can't be dealt with through reason, in an adult they can."

I read this passage aloud to Ruth and asked her if she recalled the dream and what she thought. She seemed quite upset when I read it to her. Sylvia's feelings of being abandoned by Ruth, of being on the "wrong track," of looming disaster with Ted, and of receiving poor treatment, were painfully obvious in her dream. After a long pause, Ruth told me she had no recollection of ever being told of that dream. If she had, she thinks she most certainly would have discussed its meaning with Sylvia, especially her reservations about the impending move and her murderous rage, presumably at Ruth. Still shaken, she repeated, "I don't remember her telling me that dream. And if she did, I missed it."

I wondered if somehow Ruth was reenacting aspects of her own life with Sylvia. So I asked her about her relationship with her mother. But Ruth could not talk about her mother. Almost every time I asked, she changed the subject to her father.

Ruth spoke frankly with me about her early life and her father. A brilliant, handsome and famous minister, Donald Grey Barnhouse was a charismatic speaker and admitted snob. Raising his children in Europe, often speaking French at home, and looking down on those less intelligent and well bred. He totally dominated his wife and Ruth grew up in terrible awe of him. "He was a very important person," she said.

All the children had high IQs. Ruth's was 220 and when she was 14 her father wanted her to start at Vassar. She was accepted but told to wait until she was 16 to begin her studies. In the meantime she became involved with her first husband, Francis Edmonds, who was a student at Princeton. They met in a religious youth group and fell in love. Her father refused to consent and demanded that she stop seeing him. Ruth tried to strike a bargain with her father that involved her waiting to marry, but he insisted that the relationship be broken off. I asked her why she thought her father was so opposed to her involvement with Edmonds. If she agreed to wait for marriage, why couldn't she still see him? Ruth replied, "Oedipal-shmoedipal, I guess," and we both laughed.

They eloped and they went to live with his family. Her father came and made a scene at his new in-laws' house, begging Ruth to come home. She refused. Not long afterward Ruth's mother wrote her a letter telling of her cancer. Ruth had not known her mother was sick and would never have left if she had. Within a month of marrying Edmonds she knew she'd made a mistake, but was now pregnant. She said she wished she had returned to Vassar instead of getting married. Three years later her mother died.

At age 21, Ruth continued her education at Barnard. After graduation she entered Columbia Medical School. At the end of her first year, she decided to divorce her husband. She said the divorce agreement was very favorable to him and that she had limited access to her children, Francis and Ruth. Ruth said Edmonds was hard on the children following her visits, so she stopped going. She renewed her relationship with her daughter when she was in college, but she never reconciled with her son.

Not long after her divorce, Ruth met fellow medical student William Beuscher. She fell in love with him immediately. "He looked like Clark Gable, only blond," she said. They both went into psychiatry and did their residencies at McLean. She had five more children with Beuscher, but their marriage was anything but blissful. Ruth volunteered that she "was not the easiest person to live with," but quickly added that her husband was "pretty mean to me." I asked for an example. "Little things," she said. "I would come in with a new dress and he would say things like, 'That's a nice dress. I'm surprised you had the sense to pick it out.'" Ruth said she realized after marrying him that her husband had a drinking problem. "When a man has to have four martinis within 20 minutes of getting home, you begin to wonder."

Yet Ruth remained empathetic toward her ex-husband, recalling his "perfectly dreadful childhood," a mother who ran off with another man, and his own analysis with a therapist who had a psychotic break during his treatment. She said, "I don't think of him as a son of a bitch. I think of him as a tragic hero."

As Ruth and I sat in her apartment, reliving her life, I asked what impact Sylvia's death had on her. She said she was deeply shaken and saddened. And she felt guilty. The day after her husband broke the news to her, she went to see a McLean staff psychiatrist who supervised her on the case. She said he assured her that Sylvia's suicide was not her fault. "You did good work with her, and gave her five or six years more than she would have had -- and she did all this writing. You can feel good about that," he said. And she did.

I asked Ruth if she had worried about Sylvia committing suicide when her condition worsened. She said, "I sort of was when she wrote those very depressed letters in the couple of months before she died. Because she said it was like the way she had felt before when she had done that" -- referring to her attempted suicide -- "and, so, of course I began to worry about it then. That's why I knew I ought to bring her home." When I asked Ruth how many letters she had received from Sylvia, she spread her hands apart indicating about a foot. I asked her why she burned them. "I don't know," she said. "It was after my divorce and I burned a lot of things. I was starting over." She said later she regretted burning the letters.

Ruth said that Sylvia wanted to return to America after Ted left her, but did not have the money. She anguished over whether to wire her the money and find her a job in Boston. Ruth knew she couldn't treat her again if she did, but saving Sylvia was more important. Yet she knew it was not accepted for a psychiatrist to intervene in a patient's life, even one who would no longer be in treatment. And, she said, her husband "would have exploded." Ruth regretted deciding against it.

In two separate letters written to Sylvia in September 1962, months before her suicide, Ruth gave her specific advice on how to handle her divorce. One letter is so directive it conveys an air of desperation. She advised Sylvia to get a good lawyer, and to ban Ted from her bed and the house. This letter reads more like one from a close friend or relative than a therapist.

Ted Hughes, who clearly read at least some of Ruth's correspondence to Sylvia, retaliated years later in his volume "Howls & Whispers" where he quotes directly from one of the letters in the eponymous poem, "And from your analyst: 'Keep him out of your bed. Above all, keep him out of your bed.'" Hughes goes on to suggest the "analyst" was among those who were really to blame for his wife's suicide ("What did they plug into your ears/ That had killed you by daylight on Monday?" he wrote). Hughes, of course, having left Sylvia for another woman shortly before her death, had been widely criticized in the wake of her suicide. For her part, Ruth told me that while she initially liked Hughes, she eventually grew to view him as "evil."

The impact of Ruth's advice on Sylvia remains part of the mystery surrounding the last days of her life. But Ruth's devotion to Sylvia is unlikely to be disputed. Ruth closes one letter with these words: "I have often thought, if I 'cure' no one else in my whole career, you are enough. I love you. Good luck, --Ruth B."

As I sat with Ruth in her apartment, watching her smoke the few daily cigarettes she allowed herself, I asked what her day-to-day life was like. She seemed quite depressed. Her apartment was lined with books and classical music CDs, and the living room was overpowered by the presence of a baby grand piano. I asked her if she still played. She said no. "Do you listen to your fabulous music collection." She said no. "Do you read your books," I asked. "No," she repeated. But she directed me to her bedroom, where she kept a shelf of mystery novels. She told me she didn't understand why, but these were the only books she enjoyed reading. She would start at one end of the shelf, then read each of the 20 or more that were there. When she reached the end, she began again.

Ruth had lived such an interesting life; I was disheartened to hear her recount the smallness of her world. I invited her to have dinner with me that night at the inn where I was staying. "That would be lovely," she said. "That's my favorite place. But you will have to come and get me, because I am not steady on my feet."

"Of course," I said, and returned for her at 5:30 p.m.

It was a chilly, beautiful December evening as we strolled arm in arm back to the inn. She took my arm to steady herself, but I could feel her happiness at being close to someone. When we arrived at the inn there was a small Christmas pageant in the lobby, and we joined the audience. I got each of us a cup of mulled wine, and took quiet pleasure in watching Ruth as she emerged from her depressed mood. We then went for dinner and I told her to order anything she wanted. She happily ordered a steak and a stiff drink. With no tape recorder on, she spoke much more freely and happily.

Seeing that she had not lost the ability to enjoy herself, I asked if there was anything she might still want to do with her life. She said that while she had lived and traveled all over the world, she had never seen Alaska. She had heard that Alaskan cruises were breathtaking. And it was something she could manage, in spite of her heart problems and scoliosis, provided someone accompanied her.

"Why don't you go?" I asked. She said that she had no money. She lived on her pension and Social Security and had no savings. Money had never meant anything to her, so she had always spent whatever she had. It was simply out of the question.

The next morning we returned to talking about Sylvia. I asked if she minded being known throughout her own distinguished career as "Sylvia Plath's psychiatrist." Did she feel obscured by the myth that had grown around Sylvia? She reiterated that she was happy to set the record straight and keep people from writing things about Sylvia that weren't true.

I asked what bothered her the most. This conversation took place when the tape recorder was off, so I do not have a verbatim account. But she referred vaguely to a specific poem. "Which poem?" I asked. She didn't answer. Rather, she pointed to her bookshelves, saying she thought I would find the poem there. I looked, found a copy of "Colossus," and took it down from the shelf. Ruth said something about people making too much of the title of one of Sylvia's poems. I couldn't find anything that seemed controversial in the book, so Ruth told me she was referring to the one called "Lesbos," which turned out not to be in the "Colossus" collection at all, but in the "Collected Poems."

"So it bothered you that some people thought she might be lesbian?" I asked. She said yes. I paged through the book while I listened to Ruth.

As I went to return "Colossus" to her bookshelf, I saw that Sylvia Plath had inscribed this first edition "With love" to Ruth. I couldn't help mentioning to Ruth that this book was probably worth a great deal of money, probably enough for an Alaskan cruise for two. I asked her if she would like me to make some inquiries regarding the value of the book -- or did it mean too much to her to sell? She said she didn't need the book, that she kept Sylvia in her heart. But she scoffed at my idea, saying she thought it most unrealistic to imagine the book was valuable.

Soon, Ruth and I said our goodbyes. I felt surprisingly sad about leaving her. Upon returning home to Milwaukee, I made it my mission to discover the true value of her inscribed copy of "Colossus." Eventually, I tracked down a rare bookseller, Peter Stern, whose store was located in Boston. Stern told me the book would probably fetch at least $15,000 at auction.

When I called Ruth, I couldn't help teasing her a bit after her playful ridicule of me. "What would you say if I offered you $1,000 for the book?" I asked. She said, "I'd take it. But I don't believe it's worth that much."

I responded with, "You're right, Ruth. It isn't worth that much. I spoke with a rare bookseller in Boston and it's actually worth more like $15,000." She couldn't believe it, and it took me several minutes to convince her. I put her in touch with Stern.

Then, on March 1, 1999, Ruth e-mailed me to report that she had made reservations with her niece on the Princess Line for Aug. 17. The book was subsequently sold for $14,500 and Ruth received more than $10,000; she insisted on sending me $700, to defray the costs of my visit to her. She ended her note by saying, "I often think of your visit, what a good time I had, and wish something else would bring you here again. Best wishes -- Ruth."

Not long afterward, she saw her physician, suspecting that she had an aortic aneurysm. She was right. That meant she either had surgery or risked dying at any time. She decided on the surgery to ensure good health for her trip. She e-mailed me on April 12 to tell me the news. I immediately called her and questioned the wisdom of undergoing the surgery, given her age and existing health problems. But she wanted to do it. Living her life as a walking time bomb was not something she could do. Ruth was a woman who needed to feel in control.

She gave me her son's phone number so that I could check on her progress. When I spoke to him following her surgery he said she survived the procedure, but her kidneys had shut down. She was in pain and her condition was poor. When I heard this news I was flooded with sadness. I feared that, in spite of our best efforts, Ruth might never take that Alaskan cruise.

On May 8, 1999, at Beth Israel/Deaconess Hospital in Boston, Ruth Tiffany Barnhouse died.

Shares