First there was Toni in his sparkling cocktail dress, serving drinks at Neo on Clark Street. The bar was dark, there were no windows, only a blue-lit clock. Toni had thin legs covered in track marks beneath his fishnet stockings. He brought me elegant looking drinks on a silver tray. I hid in the corners or in the middle of the dance floor. I went to Neo alone and Toni sensed my loneliness and wanted to mother me to health but it didn't happen. Toni died at three in the morning in a stranger's apartment in Humboldt Park lying next to a broken needle, blood streaming from his nose, emerald skirt riding in waves across his hips, tights ripped, a slipper dangling from his toe, eyes wide open.

Then there was Toni's friend Tony. Tony worked at Berlin, had tribal tattoos covering half his body, long, thick black hair like a horse's mane, and every year the free weekly paper voted him best bartender in the city.

Tony didn't charge me for drinks either and I hovered near his bar, an oasis next to the entrance. I danced close to Tony. I never wanted to go home. I had friends but they were sleeping, and they weren't real friends. I said, "What kind of boys do you like?" and he said, "Straight boys" and I smiled.

Tony had a fashion show and I walked the runway at Berlin in striped shorts with thin straps over my shoulders. There were so many people there, all of them high on pills, dehydrated and watching. I danced slowly past them. It was like being perfect, which is always an illusion. I was followed by a man in a straw hat, his gown covered in pale green bulbs. "Do you have any more swimsuits?" I asked Tony. "I want to go again."

"You are so vain," he said, patting my ass. I gave him a quick, sly kiss on the lips, before climbing back on the stage.

It was my stripper year. My heroin year. I danced Thursday nights at Berlin. Two sets, three songs, free whiskey, seventy-five dollars, occasional tips. They called me a go-go boy but I was really just decoration, cheap art. I scored heroin on the west side, piloting my giant car through the burnt out landscape, home of the '68 riots, the stained remnants of an assassination in Tennessee, the empty lots like broken teeth. Trash and parts everywhere, pipes protruding from the rubble, chassis on cinder blocks, men in lawn chairs on corners in front of vacant three flats. I got robbed. I got beat up. Things weren't going well. Nothing made sense. I was having the best time of my life.

I didn't make enough money on a podium at Berlin so I danced at the Lucky Horseshoe, a front for prostitutes on Halsted Street. We weren't allowed to sit between sets. We had to mingle with clients at the bar. We would stand and they would sit. "They like it when you pay attention," the owner told us. "Open seats are for customers."

I met a man who bred dogs. He stuck five dollars in my thongs after my first dance. "It's like selling people," he said, laying a rough hand on my waist. "Only it's dogs, so it's legal." Then he let out a monstrous laugh.

The going rate was $20 a day plus tips. The going rate was $80 for a blowjob down at the Ram, a dirty theater with private booths, six painted steps below street level a block away. There were sugar-daddies that came to the Horseshoe but it was up to you to parse them from the fakers and dreamers. They said, "What do you want to do with your life? I can help you." If you were a writer they were an agent. If you were an actor they were a director, a producer. If you wanted to go to school they would give you a place to stay while you got your act together. They knew someone on the admissions board. The clients at the Horseshoe were whatever you might need. But I needed to be found attractive. I needed to be loved unconditionally. And I was very angry about something.

I had a college degree.

This is all true.

It was 1995, the hottest summer on record, or so somebody told me at the time. It's a fact I've never bothered to check. They were carrying dead seniors by the dozen in a phalanx of stretchers from the nursing homes on Touhy Avenue. I lived in a squat above a garage a bullet away from the project buildings. I could make out the top of the Sears Tower from my porch. I had a roommate and during the day we would go to the slab along North Avenue Beach and lie there like seals, diving into the water every twenty minutes or so until the sun went down. We lay on the warm concrete watching the sunset and then the stars. "Life is good," he said.

Sunday afternoons I danced between films at the Bijou. Twenty minutes of porn then one boy on the stage, one boy in the audience. The men pulled their penises out, stroking themselves, sliding a dollar in my pants with their free hand. The Bijou smelled of bleach. I climbed over the seats barefoot. I was like a spider, crawling along armrests and chair backs, never touching the ground. I stayed away from the older men. They had been around too long. They were looking for a good deal. I paid special attention to a fat boy who sat in the second row. He was probably my age and I felt sorry for him. He was so obese with all this skin falling around his face. His hair was flaxen and I worried that nobody loved him the most. I was projecting my own feelings. I sat on his lap, squeezed his shoulder, kissed his neck. I wanted to be capable of loving him for more than a few minutes but I wasn't. He gave me a dollar and I hugged him, pulling his nose against my naked chest. "It's OK," I said.

There were rooms above the Bijou. Offices, a movie studio. The manager kept a picture of me in his desk drawer. He asked me to act in a bisexual porn movie. I said I didn't mind. I was put in a room and given five minutes to get a hard-on. This was my audition. The room was giant and empty with slanted beams holding up the roof and great windows looking across Old Town. I jerked off, paging casually through the porn next to the bed. The director burst in with a Polaroid camera. "Yes," he exclaimed when he saw my hard-on.

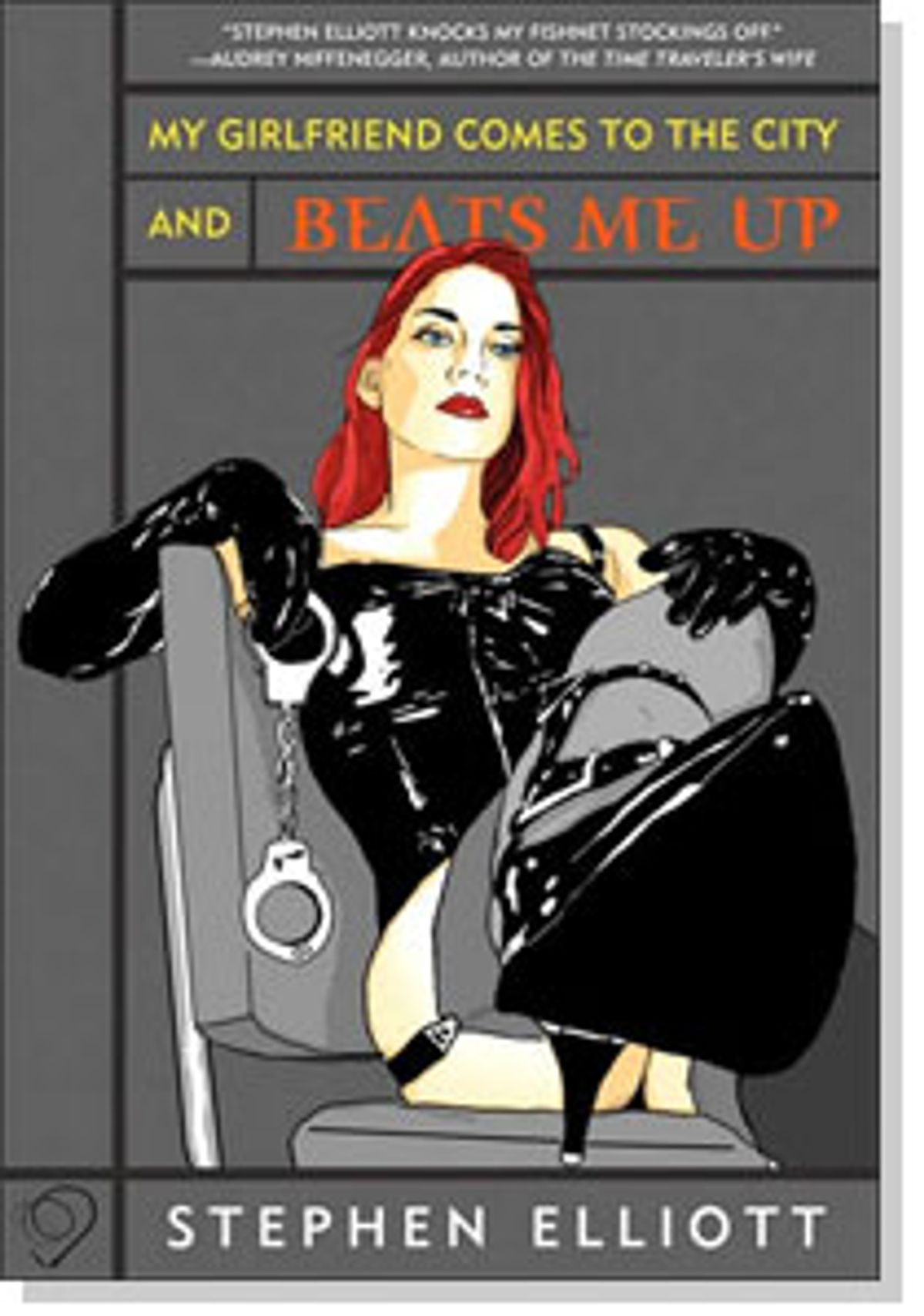

The pay was $300. I was told it was very important to be nice to the woman. She was a queen. I wanted the money but I was ambivalent about the film. What I really wanted was to be tied up. I wanted to be humiliated on tape. I wanted women with strap-ons to grip me by the throat and slide inside of me. I wanted to be wrapped in cellophane, like a present, unable to move. That was the kind of film I wanted to be in. But I didn't know how to say that at the time and people that don't know how to ask rarely get what they want.

I danced at the Manhole on lights out night. I was four feet above the floor on a square pedestal. I had to be careful not to step over the edge. Hands came from everywhere, palms stretching below my balls, fingers trying to find my asshole. I couldn't see past the elbows. "Stop it," I said softly. The music was so loud, nobody heard me.

It was my heroin year. I shot bags next to the couch and slept on the living room floor. I missed a night at Berlin. Then I missed another one. Summer was over. We stopped going to the beach. It got darker earlier. It was almost Thanksgiving. I dated Stacey, a Barbie-doll stripper with a bad coke habit and implants that didn't take. They felt like twelve-inch softballs inside her breasts. She made $400 a shift. She knew about bars in Cicero that never closed. She crashed her car and the bar maid asked if she spilled her drink. Her other boyfriend was a police officer. "He's very violent," she told me. "He wants to put his gun in your mouth and ask you some questions. He broke the lock on my door. Do you want to come over?"

After Stacey I dated Zahava. Zahava came from a good southern family. She had been a pom-pom girl. She had been to finishing school. It seemed like she was always happy. She was the only person I knew with good posture. She wanted me to go to law school. I turned her on to heroin. Years later she would tell me I was the first bad thing that ever happened to her. Zahava said I was handsome. I told her when you're a stripper you don't worry about your appearance. You always feel attractive when people are willing to pay to see you naked. It was the biggest lie I ever told. I stared at the other strippers, the bricks in their stomachs, trapezoids like baby mountains. It made me nauseous to think about. I wasn't good enough looking to dance at the Vortex but they let me in for free. I was low-rent and I knew it. I had an eating disorder and long hair. The only advantage I had over anybody was that I knew how to dance.

I was in a small room with dark wood floors on top of a big house in Evanston near the lake. I took a hotshot and passed out with blood streaming from my nose and foam gurgling at my mouth. Just like Toni a year earlier. My friend turned me over so I wouldn't choke on my own vomit, then he left me to die.

But I didn't die. Firemen came the next day. They were strong and good. They strapped me to a chair, carried me down three flights of stairs. "Where's your family?" the owner of the house asked as they hauled me past her. "What's your parents' phone number?" I didn't tell her. It was the first good decision I made that year. I was paralyzed for eight days and the nurses let me piss all over myself. When I was discharged from the hospital I walked with a limp. I told people I fell down a flight of stairs. Eventually the limp went away but it took time. And it took time to learn how to eat. I lost thirty pounds.

I didn't strip again. Or shoot heroin. I got a master's degree. I moved to a ski resort and the clients would sit at the bar unbundling their scarves. I wore black pants, a white shirt, and a patterned vest like all the other employees. We looked like dancing monkeys. Every day someone would stare at the mountains while I refilled their cup. "I wish I could trade places with you," they would say, maybe dropping a dollar into the plastic pitcher sitting empty on the counter's edge.

Shares