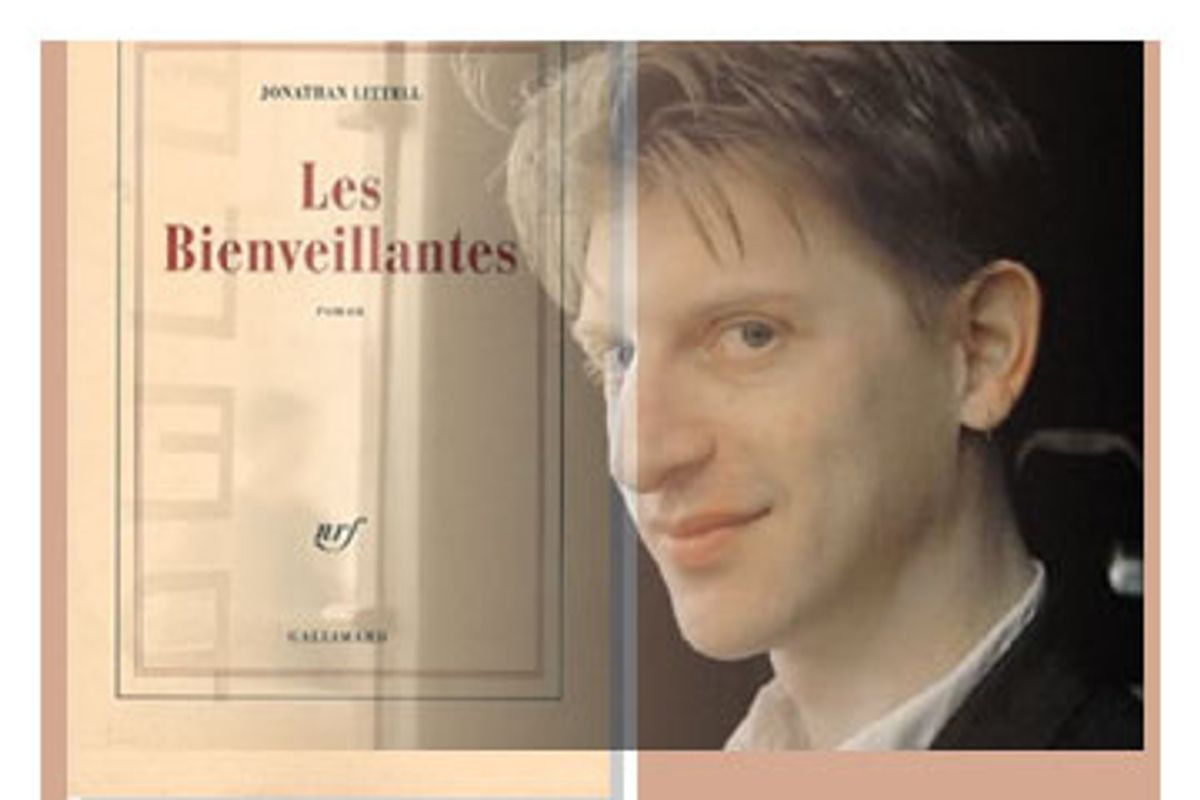

"Who hasn't heard of 'Les Bienveillantes'?" asked the French magazine Politis in its November issue. In France, at least, that question is a rhetorical one: Unless you're a hermit entirely cut off from newspapers, the Internet, television and radio, you've heard of Jonathan Littell's novel.

Upon publication by the eminent Éditions Gallimard in August 2006, "Les Bienveillantes" ("The Kindly Ones") was greeted by a volley of rave reviews -- the Gallimard Web site includes blurbs in which Littell gets compared to Flaubert, Stendhal, Norman Mailer, John Le Carré, Balzac, Bach, Jean Genet, William Styron and Couperin; for the book itself, there are misty-eyed invocations of "Moby-Dick," "Die Götterdämmerung," "Apocalypse Now," "American Psycho," "The Deer Hunter" and "Life and Fate." Not bad for a 38-year-old newcomer, and not bad for his dense 900-page brick of a novel, told from the so-not-welcoming perspective of an incestuous, gay and possibly matricidal Nazi officer, and larded with graphic sex scenes and coolly detailed musings about the most efficient way to put Jews to work before exterminating them.

It's a pretty sure bet that Oprah's Book Club will look the other way when HarperCollins publishes the U.S. edition next year, after reportedly paying $1 million for the rights.

But getting critically acclaimed and selling by the truckloads wasn't enough. Soon, the novel found itself at the heart of an animated political and literary controversy: How could a Jew write from the perspective not only of a Nazi, but of an SS officer assigned to the Final Solution? Was a gay SS Nazi too much of a cliché? Has the era of the torturer supplanted the era of the victim in the arts? Did it make any difference that Littell is an American writing in French? Was his prose stunning, wretched or merely adequate? And his grammar, how was his grammar?

Every week, nay, every day this past fall, a new Op-Ed, analysis or roundtable would appear. Since Littell himself had pretty much stopped giving interviews after an initial promo round in August, critics, historians and just about anybody with an opinion and an outlet rushed to fill the void. Consider this: A mere six months after the publication of "Les Bienveillantes," there are already two books about it -- Paul-Eric Blanrue's "Les Malveillantes: Enquete sur le cas Jonathan Littell" and Marc Lemonier's "Les Bienveillantes décryptées." In addition, the entry about Littell's book in the French version of Wikipedia is 13,637 words long, while a little classic like Proust's "Remembrance of Things Past" only gets 1,618 words and Tolstoy's "War and Peace" -- it's about Russia, you may have heard of it -- clocks in at a meager 553.

Visiting France from the U.S., where the fall's hot topic in the publishing world, relayed essentially in gossipy, sensationalistic tones, was the O.J. Simpson book and whether Judith Regan had made anti-Semitic comments, a sophisticated national literary conversation felt pretty damn exciting. I had not even heard of "Les Bienveillantes" before flying to Paris last October, but starting at the airport's bookstore, it was inescapable. So I gave in and bought the damn thing -- in a supermarket, no less. And then I actually read it from beginning to end.

So what's the really big whoop? "Les Bienveillantes" is clunkily written -- it often feels as if Littell is just regurgitating the enormous amount of research he obviously did -- and paradoxically uninvolving, considering its topic. Narrator Max Aue, a Francophile SS with a law degree and a taste for Rameau, finds himself, Zelig-like, present at various key times and places of WWII: He hangs out with French right-wing ideologues Lucien Rebatet and Robert Brasillach in Paris; witnesses the mass extermination of Jews in Ukraine; gets wounded in Stalingrad; returns to Berlin, where he organizes the use of prisoners to sustain the war effort; goes off to inspect concentration camps; somehow ends up in Hitler's bunker.

Through it all, Aue somatizes (he vomits constantly and is often victim of diarrhea), reminisces longingly and achingly about his relationship with his twin sister, indulges in aesthetic ruminations on music and literature, gets sodomized by rough trade and junior officers, and ponders the difference between rational and irrational anti-Semitism.

Only by the end does Littell's writing get into some kind of groove, especially in a lengthy semi-hallucinatory sequence that brings to mind Pasolini at his most scatological. But to get there, you have to labor through hundreds of paragraph-less pages larded with dry facts, flat descriptions and untranslated references to German military ranks. (I'm surprised none of the commentators seems to have mentioned Victor Klemperer's prescient 1947 study "The Language of the Third Reich," about the Third Reich's use of language to manipulate people, because Littell's constant use of terms such as "Hauptscharfuehrer," "Obersturmfuehrer," "Brigadefuehrer," "Obergruppenfuehrer," etc., is dizzying to the non-Germanophone, but also effectively suggests a society literally based on strict hierarchy. It's one of the few purely literary tricks in the book.)

What happened, then, was a swift reverse of what usually takes place in the U.S.: The debate about the book turned out to be a lot more interesting than the book itself. And in the process it revealed quite a bit about France and its complicated tango with literature, history and that big elephant in the lit room -- money.

For instance, take the literary prizes -- Littell sure did. As soon as the initial excitment had started to calm down, the finalists for the fall prizes were announced and all hell broke loose again. Now, France loves literary prizes: The comprehensive Web site Prix-litteraires.net lists 982 of them -- not bad for a country of 64 million people. Out of those 982, however, emerge biggies with direct influence on sales (Prix Goncourt, Prix Renaudot, Prix Femina, Prix Interallié, Prix Académie Française, Prix Médicis). In an unprecedented coup, "Les Bienveillantes" was long-listed by all six; it ended up winning both the Académie Française and the Goncourt, only the second twofer in the prizes' history.

It's obvious that the foremost reason "Les Bienveillantes" has attracted such passionate interest is its basic premise: The story is told by an unrepentant SS officer. It certainly helped Littell's credibility that he had firsthand experience of the cruelty men are capable of, having traveled to the likes of Bosnia, Afghanistan and Chechnya when he worked for Action Against Hunger, but that still didn't prevent many from reacting viscerally and violently to his choice of a first-person narration. In protest, a member of the Prix Goncourt jury symbolically voted for Elie Wiesel, who wasn't nominated. Best-selling author Christine Angot, whose "fiction" is transparently autobiographical, trashed Littell's book in the glossy gay monthly Tetu, arguing that as a Jew, Littell couldn't possibly write from a Nazi's perspective (she didn't seem to have a problem with a law-abiding man writing about killing, or with a married father writing about gay sex).

Experts obviously couldn't help piping in. A historian, for example, called "Les Bienveillantes" a showoffy prank in Le Figaro. One of the most prominent French authorities on the Holocaust vigilantly guarded his turf while harping on the book's graphic descriptions of sex, bodily functions and violence. As Natasha Lehrer wrote on the Jewish cultural webzine Nextbook: "[Shoah director] Claude Lanzmann, who has said that he considers himself and [American historian] Raul Hilberg the only people who understand how to represent the Holocaust, described Littell's novel as nothing less than 'a poisonous flower of evil' in Le Journal du Dimanche. 'In spite of the best efforts of the author,' he goes on to say, 'these 900 stormy pages are completely unconvincing ...The book as a whole is simply a scene setter and Littell's fascination for the villain, for horror, for the extremes of sexual perversion, work entirely against his story and his character, inspiring discomfort and repulsion, even though it's hard to say against who or what.'"

Which brings us to a particularly rich angle, that of the book's style -- an angle made particularly acute by the fact that Jonathan Littell, the son of popular author Robert Littell ("Vicious Circle," "The Company"), is American but, having been raised in France, chose to write in French. Not only had some unknown won both the Goncourt and the Académie Française, but an American unknown had won! The head scratching was endless: Was the book stylistically worthy or not? Was it loaded with grammatical mistakes and "Englishisms"? If yes, did it matter? Why were French novelists -- presumably lost in navel gazing and/or still under the nefarious influence of the experimental nouveau roman school -- seemingly unable to demonstrate similar breadth, erudition and ambition?

In a November interview with Le Monde, Littell himself pointed out that one of the possible reasons for his book's success was "a literary trend -- a demand for bigger, more fantastic, very constructed novels." Which, of course, is exactly what many say contemporary French novelists are unable to provide, a common complaint being that nobody in France knows how to write large-scale stories anymore.

And then there were the malicious rumors, also linked to the author's nationality: One implied that Littell Sr. was the actual author and Littell Jr. a mere translator, another that the book had secretly been written by its editor at Gallimard -- theories that feel lifted from one of Littell pere's thrillers. That gossip quickly died down, but not the formalist attacks. Among the mildest critics was the lit professor who termed the novel "neoclassical" in Libération. The most obsessive endeavor was by one Bruno Janin, who went through each of the novel's 894 pages with a fine-tooth comb, looking for grammatical and spelling mistakes, awkward turns of phrase and awkward word choices. Mostly he pointed out instances where something read like a too-literal adaptation from English, but he also let loose on general editing matters. Obviously plenty of badly written books come out every year in France -- the vast majority of them written by native French speakers -- but nobody ever dissects them with such single-minded ferocity.

Another point closely related to Littell's Americanness touched on the very structure of the French book business: Littell had peddled his manuscript via an agent (and under a pseudonym), a rare occurrence in France where writers tend to deal directly with publishers. Some wags wondered if using an agent betrayed a typically "Anglo-Saxon" commercial imperative -- despite the fact that an increasing number of French writers, including such heavy hitters as Michel Houellebecq, Emmanuel Carrère ("The Mustache") and Fred Vargas ("The Three Evangelists"), now use agents. The magazine Les Inrockuptibles magnanimously allowed that at least Littell was helping all authors by popularizing the use of agents in the French publishing world, which to many still feels ruled by antiquated rules and secrecy (by January, sales figures for "Les Bienveillantes" fluctuated between 395,000 and 549,200 -- a 39 percent difference), and where the house usually wins. As an article in Le Monde pointed out, "With 'Les Bienveillantes', we're in a situation in which the author seems to be earning rather more money than his publisher, which isn't that frequent when a book does well."

In the end, "Les Bienveillantes" isn't a great book, but we should be glad it exists. First, it launched an exciting debate of ideas, real ideas. And on a literary level, "Les Bienveillantes" may incite French writers to pick up the gauntlet and shake up their dormant ambitions.

But it's the very intimate relationship, the one between an author and a reader, that Jonathan Littell has indirectly reenergized: He must be hailed for prompting renewed interest in -- and in some cases the wholesale discovery of -- other, usually better, writers. After reading yet another reference to Vasily Grossman's "Life and Fate," for instance, I picked up that 1959 novel (about the battle of Stalingrad, roughly speaking) out of sheer curiosity, and was stunned and delighted to discover a genuine masterpiece that does display the narrative complexity and anguished humanity absent from Littell's book. If "Les Bienveillantes" engenders similar discoveries among American readers when it comes out here, its very existence will be justified once more.

Shares