"May I take your newspapers?"

The flight attendants always make it sound like they're doing you a favor. I fly a lot nowadays, and I know the poor attendant is only trying to save cleanup time later. But this question always riles me, because lately everybody and his Aunt Lillian wants to take away our newspapers. Circulation is down. Newsroom paranoia, never exactly dormant even in the best of times, is up. And editors are cutting book reviews like they're going out of style -- which, if we're not careful, they just might be.

To its credit, the National Book Critics Circle is not taking any of this lying down. It has posted a list of tips on how to help save book reviews here. It's circulating a petition here to reinstate Teresa Weaver, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution's gifted, recently cashiered book editor. Most enjoyably, the NBCC's already compulsively readable blog, Critical Mass, has posted jeremiads about the crisis not just from critics but from a steadily massing murderers' row of authors: Nadine Gordimer, George Saunders, Richard Ford, Roxana Robinson, Andre Codrescu, Rick Moody, Stewart O'Nan.

Will this campaign work? The facile answer is, say you're a newspaper publisher. You've got some bolting stockholders on line 1 and some angry brilliant midlist writers on line 2. Which call would you take? But the intelligent answer is, as always, nobody knows. Newspaper publishers aren't stupid, just scared. I'd be scared too if I suspected my readers were dying off unreplaced. Come to think of it, as editor of the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review from 1998 to 2000 and the paper's book critic until '05, I used to suspect exactly that.

It was only a hunch, because a newspaper prefers its journalists to not know too much about their readership, just as it prefers them to not know too much about their relative salaries. So long as a paper withholds this information, it can still theoretically tell every employee that his or hers are the least-read, best-paid bylines in the building. Newspaper Web sites are only too happy to divulge the top 10 most read or e-mailed stories of the day; the bottom 10, not so much. Still, to judge by the torrential hemorrhaging of book coverage in just the past couple of months, you might think that book coverage owned a lock on last place.

Instead, strong anecdotal evidence suggests that book reviews fall somewhere near the middle. So why don't editors feel as sentimental about them as they do about plenty of other stories that won't ever knock terrorist attacks or wardrobe malfunctions out of the top 10? For one thing, freelancers contribute most of the copy to newspaper book review sections, and freelancers cost a few extra bucks. For another, trying to publish a review of every halfway interesting new book each week is like trying to review every new video on YouTube. It's beyond hopeless. So why should we blame some harried arts editor for thinking, "That beat's uncoverable. Let's just give up and run sudoku-plus instead."

That editor might almost have a point, if book reviews and the people who write them weren't what biologists like to call an "indicator species." An indicator species is the newt or worm in an ecosystem that nobody much notices until it starts to disappear. And even then, who really misses another polliwog -- until six months later when, suddenly, even the buzzards are dead?

Like it or not, the indicator species for American daily journalism is the book review. Newspapers were cutting book coverage before the current flurry, among other places in Detroit, San Jose and Boston. Without exception, losing their book pages failed to stanch either reader loss or red ink. Were these papers already in trouble before they started cutting book coverage? Of course, but what did their publishers expect by further alienating people who like to read -- the one constituency no newspaper can survive without? Put another way, how can institutions that cover electoral politics be so deaf to every campaign's first commandment, namely, "Shore up your base"?

Sometimes it seems as if embattled newspapers took the "Reading at Risk" report put out by the National Endowment for the Arts (where I work these days) as a rationalization for further cuts instead of a call to action. The study showed that only about 47 percent of Americans can say they read a book for pleasure the previous year. That marked a decade-over-decade swan dive from 1992, and a power dive from the decade before. Worse yet, as fast as the reading numbers are sinking across the board, for teenagers they're absolutely cratering. And teenage boys? Check out those demoralizing numbers, if you have a fainting couch nearby.

So maybe it's not surprising that the population of stand-alone Sunday book review sections in America is now down to about four: the Washington Post Book World, the New York Times Book Review, my dear old incredible shrinking San Francisco Chronicle Book Review, and would you believe the plucky, sainted San Diego Union-Tribune? Add in the Chicago Tribune, if you can get used to Saturday delivery. And if you don't mind a new reversible Books/Opinion hybrid (which looks a little like an old Ace Double sci-fi paperback), don't count out my hometown Los Angeles Times.

Less remarked on is the utter disappearance of regular, non-editing book critics outside Washington and New York. Three of the surviving half-dozen have won Pulitzers, which helps. But since 2001, Pulitzer criticism juries have stiffed the book beat and recognized automotive and fashion writers. This only testifies to the diminishing cachet of book reviewing in American journalism, even among that journalism's supposed guardians at Columbia University. Of course, there aren't that many ungarroted necks left to hang a medal around.

So in 2005, I became what may turn out to be the last full-time book critic in America to leave his job voluntarily for anything other than semiretirement. Since my departure, the Chronicle certainly hasn't felt the urge to find a new one. To that newspaper, as to almost every other paper in America, a book critic is like a fancy antique car -- almost a relief when it finally gives out. They cost so much to insure.

What I left book reviewing to do isn't, I hope, completely irrelevant to this conversation. I joined the NEA mostly to direct a new initiative called the Big Read, which aims to restore reading to the heart of American life. Under it, cities and towns apply to run a one-city, one-book program, sometimes called a CityRead. Since their earliest annual incarnations in Seattle and Chicago a decade or so ago, CityReads have brought people together to celebrate and argue about all sorts of books in a kind of monthlong festival. Bookstores sell the chosen title like crazy, libraries check it out by the hundreds, and suddenly strangers have something in common more interesting to talk about than the weather.

Only problem is, not every city or town is blessed with a library budget the size of Chicago's or Seattle's. (Jackson County, Ore., is voting on a measure this month just to keep its libraries' lights on.) So the NEA hatched the Big Read, whereby burgs as small as Wallowa County, Ore. (population 7,000), or as big as Miami choose a book from our growing list and apply for a modest chunk of the green and crinkly. On top of the grant, we create and ship readers and teachers guides and educational CDs of a caliber that most communities might never manage on their own. Our growing menu of books to choose from started out looking fairly canonical -- F. Scott Fitzgerald, Zora Neale Hurston, John Steinbeck -- but lately everybody from Dashiell Hammett to Cynthia Ozick is crashing the party.

I bring all this up for two reasons, one big, the other enormous. First, none of the 21 writers so far on the Big Read list would be there if it weren't for timely attention from at least a couple of long-forgotten book reviewers. Where would Steinbeck be -- a man so unpersuaded of his own genius that he wrote "The Grapes of Wrath" and then seriously considered becoming a marine biologist -- if not for early championing by another San Francisco Chronicle book critic, Joseph Henry Jackson. More important, where would American literature be without all the great writers who got a leg up from a smart critic when they needed it most?

Still, as important as the crisis in American book reviewing is, the underlying crisis in reading is practically sawing the country in half. Forget red states and blue states. The implications of a republic where half reads and the other doesn't -- not can't, just doesn't -- are simply horrifying.

This would all be bad enough if it weren't for one further filthy secret: Too many of us, subconsciously, like it this way. By "us," I mean the people who still read books, book reviews, newspapers and, yes, Salon. There's a furtive, beleaguered, unacknowledged glamour in feeling like the last bastion of civilization, the saving remnant beset on all sides by the forces of ignorance and greed. Who lives for baseball more than a Cubs fan? Everybody loves a lost cause -- sometimes so much that we forget to fight for it.

But the fight to get America reading again is too important, the stakes too high, to resign ourselves to failure. That's why I'm about to abandon all pretense of seemliness and exhort everybody within sight of this page not just to join the NBCC's campaign to save book reviewing but to help bring a Big Read to town. Agitate for book reviews, absolutely, but while you're at it visit neabigread.org and help your local library or nonprofit pull off a Big Read. Over and over, what makes the program work every time is the dedication of all the volunteers and librarians and teachers and, frequently, newspaper people who pitch in.

It would be so easy to wax cynical about high-minded, uphill campaigns like ours and the NBCC's. Take it from me, dyspepsia used to be my stock in trade. But imagine a country where readers aren't even a minority, but an aberration. Picture a country where newspapers gut book coverage and everything else that made them worth saving in the first place -- like Fogg at the end of "Around the World in Eighty Days," burning his own boat piecemeal for fuel. Imagine all that, and pretty soon writing a letter to the editor, or helping gin up a Big Read application for spring by the July 31 deadline, starts to look less like a sacrifice and more like a mitzvah.

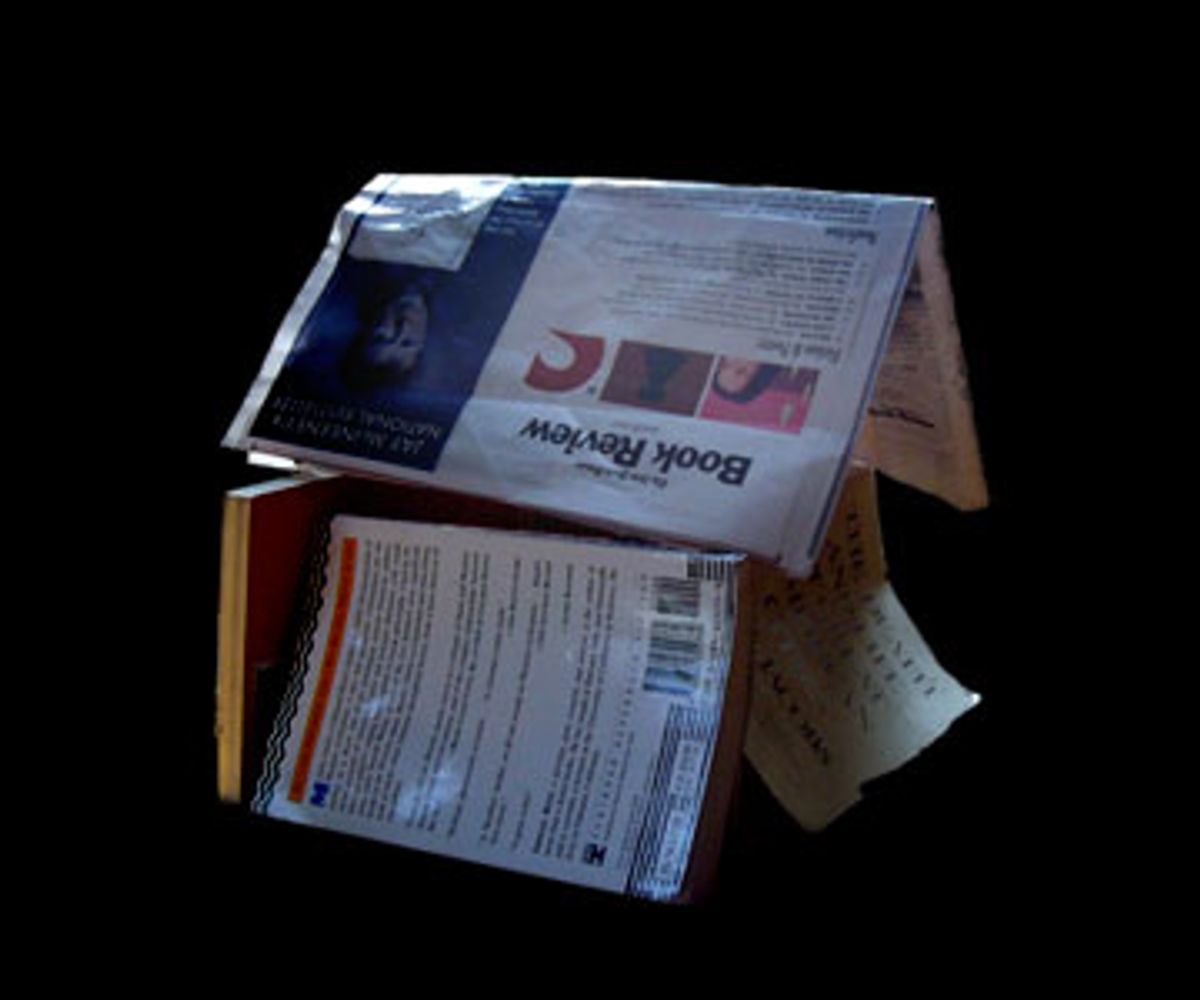

OK, so enough guilt, already. That flight attendant is still waiting: "May I take your newspapers?" The question only chafes because something so precious to us looks, to the attendant, as disposable as the foil bag your honey-roasted peanuts came in. But it's not the attendant's fault if nobody ever showed him or her that a decent paper and its readers can knock an autocrat off the throne, or put an unheralded writer on the map. So the next time that attendant asks to take your newspapers, instead of your wanting to snap, "No, you may not," maybe something a tad more conciliatory is in order. Something along the lines of "No, but you can borrow them." Or my new, less obnoxious comeback: "All except the book page. I'm not done with that yet."

Shares