He talked about how difficult it was to be a novelist in a world seething with advertisements and entertainment and knee-jerk knowingness and facile irony. He wrote about the maddening impossibility of scrutinizing yourself without also scrutinizing yourself scrutinizing yourself and so on, ad infinitum, a vertiginous spiral of narcissism -- because not even the most merciless self- examination can ignore the probability that you are simultaneously congratulating yourself for your soul-searching, that you are posing. He tried so hard to be sincere and to attend to the world around him because he was excruciatingly aware of how often we are merely "sincere" and "attentive" and all too willing to leave it at that. He spoke of the discipline and of the abrading, daily labor such efforts require because the one imperative that runs throughout all of his work is the intimate connection between humility and wisdom.

Perhaps someday we'll be offered an explanation for why David Foster Wallace took his life on Sept. 12, but any reader can see how his fiction had, in recent years, moved into greater darkness. "Infinite Jest," though "sad" in accordance with its author's stated intentions, bubbled with humor and the sort of creative energy that is a kind of hope, the belief that, in the telling, the tale might redeem what is told. The story collection "Oblivion," the last book of fiction Wallace published before his death, shows character after character flailing away at the impossible task of making life endurable. While Don Gately and Hal Incandenza, the heroes (more or less) of the novel "Infinite Jest," fight to stay on the road through the desert, the men and women of "Oblivion" mostly can't manage to convince themselves that such a road exists.

None of them more so than Neal, the suicidal narrator of "Good ol' Neon," a man who, we learn at the end, is based on a former classmate of Wallace's. The story's final paragraph sums up the preceding 40 pages as the thoughts flickering through Wallace's mind as he glimpses the dead man's photo while flipping through his high school yearbook. It's impossible to resist the idea that the fictional Neal's motivations in ending his life -- he regards himself as utterly "calculating" and "fraudulent" -- were Wallace's own, but such conclusions would only have multiplied the author's despair.

Wallace believed, I think, that one way out of Neal's labyrinthine artificiality, out of his preoccupation with selling "a certain image" of himself to every person he met, was to practice a rigorous, imaginative compassion. If Wallace could persuade himself that he was able to conjure even an inkling of Neal's inner life, then he, at least, might feel a little less alone. By getting it down on paper, he could further subdue that loneliness in other people, as other writers had subdued it in him. This was, in part, literature's purpose, a task to which it was uniquely suited. Perhaps, at times, it also became Wallace's purpose, and kept him alive a little longer as a result. So if we decide that "Good ol' Neon" is primarily about Wallace's own suffering, we betray him. That would amount to insisting that no matter how hard he tried to escape, he remained trapped in himself, concerned only with himself.

Perhaps in the end, that's what he thought, but he was wrong. He was my favorite living writer, and I know I have plenty of company in that. His detractors accused him of being show-offy, of calling attention to his own cleverness, but they, too, were wrong. He meant, with his footnotes and his digressions, to acknowledge the agonies of self-consciousness and the "difference between the size and speed of everything that flashes through you and the tiny inadequate bit of it all you can ever let anyone know." Point taken. Still, I read about his characters, each tennis prodigy and recovering addict and transvestite hooker and yuppie and ad exec and game show contestant and closeted political aide, and thought: Hey, I know you. Maybe it was an illusion -- Wallace would have been the first to admit as much -- but it made me feel less alone, too.

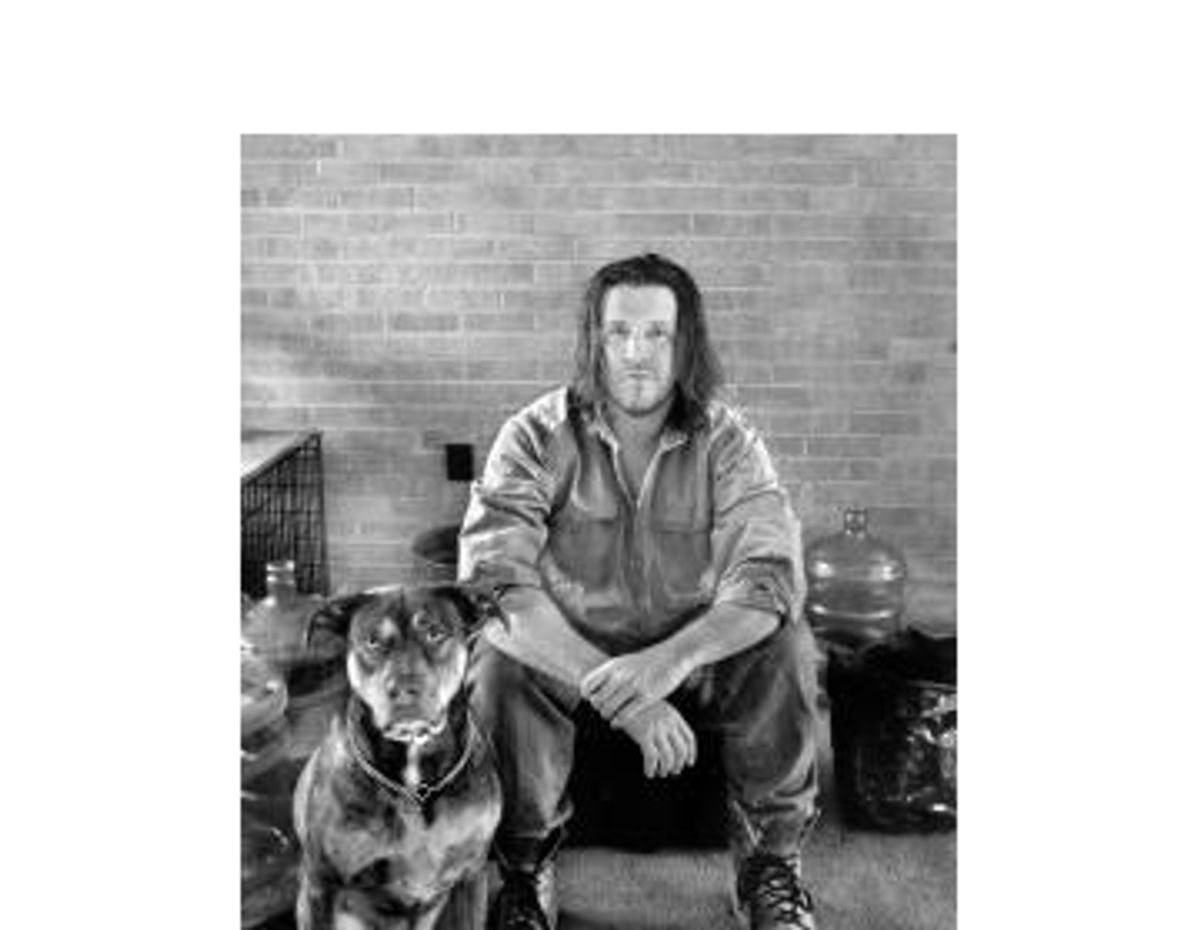

I interviewed Wallace once, in 1996, and communicated with him occasionally over the intervening years. A reader once asked me to ask him to write a letter to a gravely ill friend, and he did. I don't doubt that those who knew him better, including his many students, can further testify to his kindness and generosity. Really, though, I knew him as a reader knows a writer. I thought I could see him, even if he couldn't see me, even if he couldn't (clearly) see himself. Again, less alone.

Every author wants to sell books, to please his or her publisher, to reap critical accolades and to bask in the admiration of colleagues, and Wallace did want those things, at the same time that he was more than a little embarrassed by such desires and acutely aware of the fact that none of it could make him happy. However, all great writers -- and I have no doubt that he was one -- have a preeminent purpose: to tell the truth. David Foster Wallace's particular vocation was to allow us to see just how fraught and complicated, how difficult yet how necessary, that telling had become -- not just for him, but for all of us. What will we do without him?

Shares