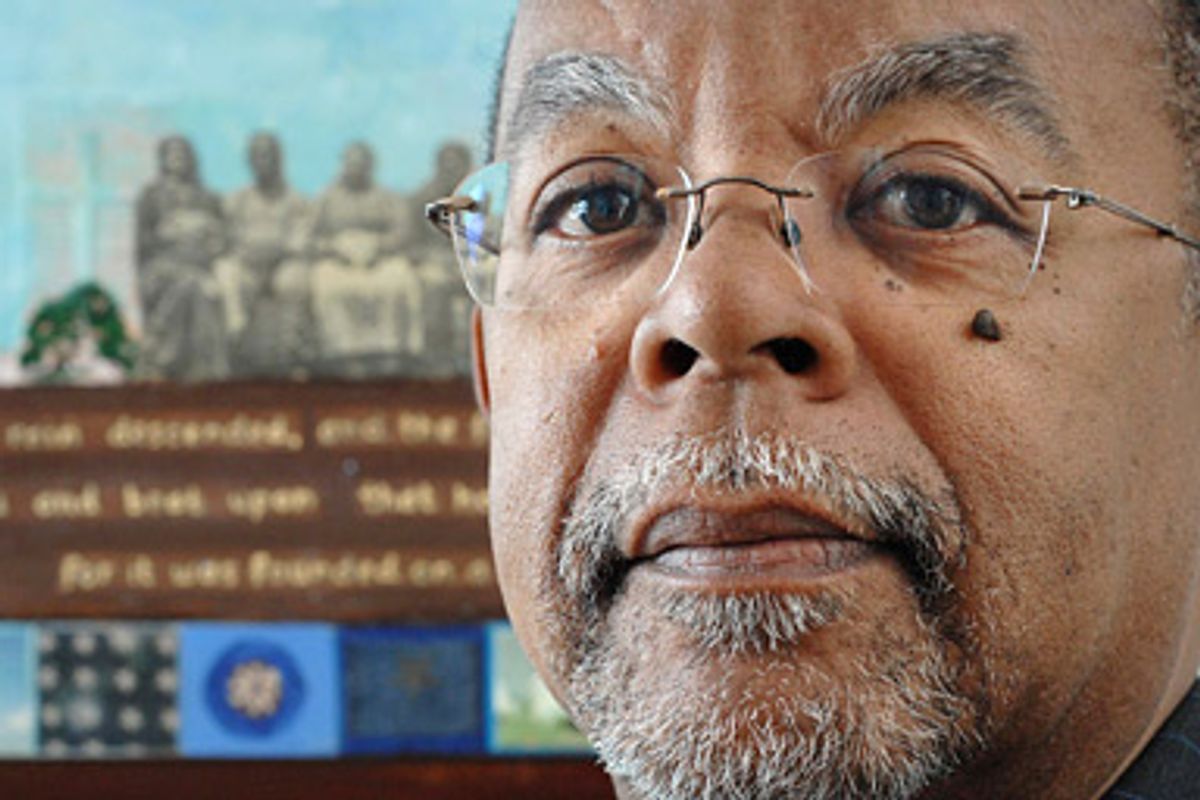

When I heard that prominent black Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. was arrested for breaking into his own home in Cambridge, Mass., it made me proud of America. It may seem paradoxical to focus on the positive side of the preeminent scholar's public humiliation. This is, after all, a distinguished staff writer for the New Yorker, the man who helped Oprah find her roots. It may seem that there's no positive side at all. (His own neighbor, a Harvard magazine employee, didn't recognize him and called the cops. How pathetic is that?)

But last night I happened to be reading a book that put the whole incident into context, a volume that never fails to chill me: "We Charge Genocide," a petition brought before the U.N. in 1951 that makes a very convincing case for defining the treatment of African-Americans in the U.S. as a genocide. This remarkable book consists, in part, of a litany of shocking bias crimes committed against black citizens across the country -- and only documented ones occurring between 1945 to 1950. A typical entry reads: "February 13 -- ISAAC WOODWARD, JR., discharged from the Army only a few hours, was on his way home when he had his eyes gouged out in Batesburg, South Carolina, by the town chief of police, Linwood Shull ... [A]n all-white jury acquitted Shull after being out for 15 minutes." And so on, for 50-odd hair-raising pages. Believe me, Toni Morrison couldn’t top it.

So the Gates story makes me thankful that it’s not 1945 anymore, the year when, on Dec. 22, Cab Calloway was "slugged by a city policeman" in Kansas City and needed "eight stitches ... in his head." Hallelujah that the incident did not result in Mr. Gates' lynching, death and dismemberment (followed by a hefty fine), though the worst-case scenario of conflict between blacks and the police has followed this pattern too often in the past -- and still flares up, but not to the same degree, and blacks have considerably more recourse under the law. I’m reassured that the public, the police and the media no longer officially condone racial profiling and violence against people of color even if we still slip into the pattern, or echo it, from time to time. There is even some debate among letter writers on news sites about whether Gates-gate constitutes a case of profiling at all. In the past such bias would go without saying and never create a ripple, much less an outrage -- like the stories in "We Charge Genocide," which, if anything, only convinced the U.N. to define genocide in a way that would keep the U.S. from facing our race problem.

I’m not saying that our modern transgressions are excusable just because arresting a Harvard professor in his own home is milder than blinding a black veteran, or that outrage is inappropriate. I’m simply rejoicing in the fact that the work of historians like Gates and documents like "We Charge Genocide" have made injustice visible to those who might not have examined it before -- especially its perpetrators. This does not apply only to whites, by the way -- I’m also including the ingrown racism of people of color. The majority of us would rather forget the hideous violence that underscores the history of race relations. We’ve made progress, as Gates himself has noted, and our impatience with the process is what causes it to move forward in the first place. The fact that Gates, who knows this narrative so well, has found himself forced to play a role in the real story of discrimination is, to me, like something out of a movie -- it’s as if he’s awakened from a nightmare about slavery to discover a shackle around his neck.

This intrinsic irony is why, though I’m sure Mr. Gates’ arrest was traumatic for him personally -- and if I knew him other than as a public figure I wouldn’t say this at all -- I find it difficult to contain my joy or laughter when I think of this incident purely as a cultural event, especially now that the charges have been dropped and Gates has only sustained injury to his pride. First of all, I’m elated that black Harvard professors exist, though I’m sure there are not enough of them; secondly, that what happens to any Harvard professor, regardless of race, can become worth reporting on; and thirdly, that this event will probably make members of the Cambridge Police Department and other P.D.s think twice before they arrest another black man. Imagine the confusion it will cause the po-po -- "Uh-oh. Is this brother a professor, too? What does Cornel West look like?” Maybe some ordinary, untenured black men in the street will get some much-deserved benefit of the doubt now.

I'm even happier that the net result of this contretemps may be that Gates, whom I consider a hero, will most likely gain two things: increased fame, which will hopefully lead more people to his work, and, dare I say, a bit of street cred, like Martha Stewart’s stint in jail. No one can accuse Henry Louis Gates Jr. of living in an ivory tower anymore.

Gates-gate also brings to life Malcolm X’s famous joke: Q: What do white racists call a black man with a Ph.D.? A: Nigger! The arrest of Gates exposes for us the truth of this meta-joke (it belongs to that category of jokes that are only jokes because of what we expect jokes to do), and reminds us how unsubtle racism is at its most virulent.

The conflicting statements of Gates and arresting officer J.P. Crowley also measure exactly the gap between, well, to be as accurate as possible, officers of the law and people they perceive to be black. (Genetically speaking, Gates is biracial, as he meticulously documented in his PBS series "African-American Lives," though culturally and politically ... it gets complicated.) Though they describe the same event, the two accounts are so substantially different that we can only pray for the leak of a YouTube video to set the record straight. Gates depicts himself calmly requesting the name and badge number of officers who had already entered his home and reveals gradually his realization that profiling might have occurred.

If we’re to believe Crowley’s police report (which I am disinclined to do, frankly), a Harvard scholar, faced with arrest in his own home, suddenly switches codes and begins to talk like George Jefferson -- "Ya, I’ll speak with your mama outside!" This cry doesn’t sound so much to me like the gent who edited "The Norton Anthology of African American Literature." I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that if there’s one thing a successful academic knows how to respect, it’s authority. What’s more, in the battle of cop versus professor, it’s a safe bet that the African-American historian knows better what’s at stake when it comes to keeping an accurate record of the past.

Shares