A hundred years ago it was rarely diagnosed in children. In the intervening timespan the number and type of diagnoses have exploded. Moreover, the number and type of treatments have also exploded. The favored treatment usually involves powerful medications with serious side effects. Big Pharma has made a fortune from these medications and is constantly searching for new variations to patent and sell.

I’m talking about childhood cancer, but I bet you thought I was talking about childhood mental illness. After all, everyone in contemporary society knows that childhood mental illness is over-diagnosed, that drugging children is the preferred method for dealing with the normal problems of childhood, and that normal children are being treated with powerful psychotropic medications simply because they are quirky and authentic.

That’s what Judith Warner (author of “Perfect Madness”) thought, too, when she sold a proposal back in 2004 for a book that would explore the over-diagnosis of mental illness and over-treatment of children with psychiatric medication. She knew it for all the reasons listed above: Childhood mental illness was rarely diagnosed in children 100 years ago; since then the number and type of diagnoses have exploded; the number and type of treatments have also exploded; the medications used to treat childhood mental illness are powerful and can have serious side effects; Big Pharma has made a fortune from these medications and is constantly searching for new variations to patent and sell.

But the same things apply to childhood cancer, and no one is suggesting that childhood cancer is over-diagnosed, that chemotherapy is the preferred method for dealing with the normal problems of childhood, and that normal children are being treated with chemotherapy simply because they are quirky and authentic. The conclusions we have drawn from the dramatic increase in the diagnosis of childhood mental illness are wrong. Though childhood cancer was rarely diagnosed 100 years ago, that’s not because it didn’t exist. It’s because we didn’t have the tools to recognize it or any effective medications to treat it. Similarly, we need to consider the fact that childhood mental illness is not new, just as childhood cancer is not new; we just lacked the tools to recognize it and any effective medications to treat it.

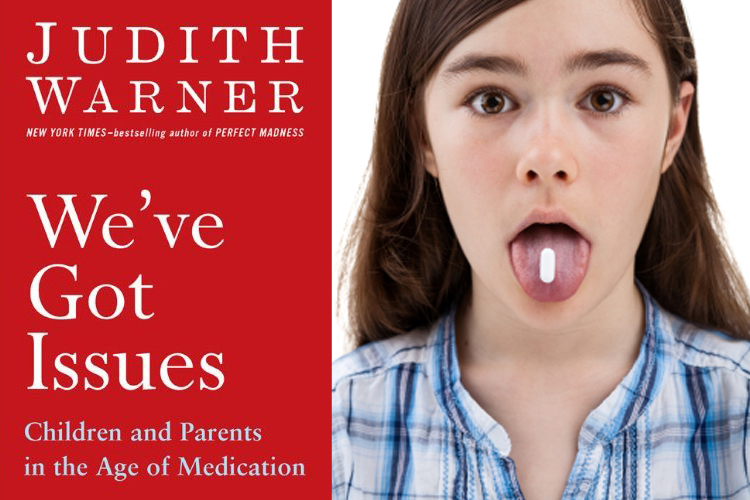

In “We’ve Got Issues: Children and Parents in the Age of Medication,” Judith Warner has written a brilliant and compelling book, a must-read for any parent who has a child who is miserable and struggling. It is also a must-read for anyone who thinks he knows that childhood mental illness is over-diagnosed and over-treated. Parents who have dealt with mental illness in a child will find solace here, because someone has finally acknowledged that their child’s “issues” are not the normal problems of childhood, that they struggled for years against putting their child on medication, and that their most fervent wishes are not that their child will get A’s in order to get into a competitive college, but merely that he or she will be able to live outside an institution without hurting anyone.

Warner details how she came to write a book that is 180 degrees opposite of what she initially intended. It happened because she talked to parents and psychiatrists and looked at what the medical literature actually shows. And Warner details how she and many others came to believe that childhood mental illness is a fraud perpetrated on society by Big Pharma:

The web of belief — let’s call it the “naysayer” position … is the new face of mental health stigma in our time. It is voiced as concern, as a desire to save children, as a wish to give childhood back to kids, but what it really is, most of the time, is prejudice. And it’s a poison.

People who share the views I used to espouse don’t see themselves as prejudiced. They believe they are raising their voices in protest of a world that’s gone mad, and, in particular, providing necessary pushback against a pharmaceutical industry that’s grown way too powerful, with the collusion of our government and far too many research scientists and clinical practitioners.

Warner is not naive:

I want to say here as strongly as I can that I agree that many aspects of today’s world of childhood are toxic and that I deplore both the irresponsible marketing practices of Big Pharma and the failure of our government and research institutions to stand up against it.

But we must not confuse one issue with another:

That said, I also fiercely believe that the social climate of family life, the machinations of the pharmaceutical industry, and the lives of children and parents dealing with mental health issues have to be viewed as separate phenomena. Not because they aren’t interconnected, but because if you let your feelings about industry and society cloud your vision of parents and children, you run the risk of not seeing them at all. (Emphasis mine)

We have used the wrong measurements to determine whether childhood mental illness is real (the rise in diagnoses, the rise in medications, the profitability of the treatment), and therefore we have reached the wrong conclusions. Children with mental illness always existed; we just never saw them because of prejudice, labeling (“mentally defective”) and institutionalization. It would be a terrible sin if we continue not to “see” them today because of our feelings about contemporary society or our feelings about the pharmaceutical industry. Warner points out that real children and real parents are suffering terribly. We should not compound their suffering by pretending that childhood mental illness does not exist.