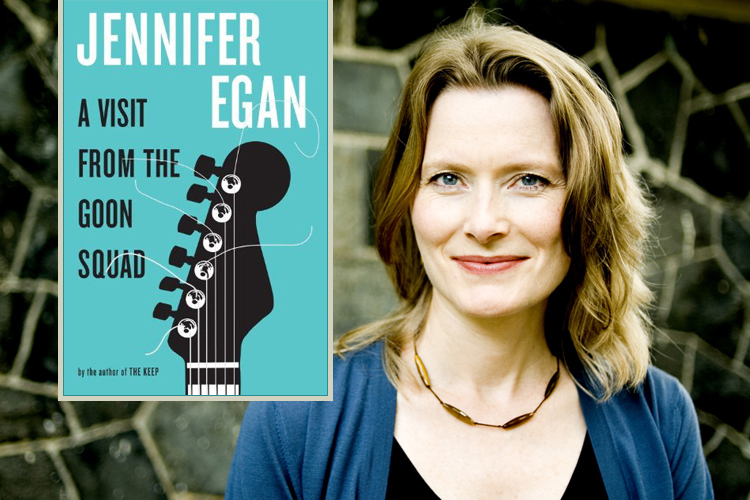

Like a good drug trip, a good novel needs an anchor: a captivating time or setting or protagonist. “A Visit From the Goon Squad,” the new novel by National Book Award finalist Jennifer Egan (“The Invisible Circus,” “Look at Me,” “The Keep”) doesn’t have one. And yet, just when you’re thinking you can’t possibly deal with yet another set of characters and circumstances — the San Francisco music scene of the 1970s, the louche back streets of 1990s Naples and New York, the post-suburban, post-apocalyptic California desert of the future — just when you’re thinking, “Egan’s good, but this time she’s gone too far,” you turn the page and — bam! — hooked all over again.

Trying to “follow” the “plot” of “Goon Squad” is like trying to count the pores on your arm while tripping: tempting, yes, but a distraction from all the pyrotechnical fun. With Egan you’re in the hands of a master, so relax and let it all wash over you: time folding into itself, people running into their former and future selves, and most of all, the writing, the writing, the writing. In the book’s opening scene, for example, 35-year-old Sasha steals a wallet from a hotel guest and then, rather than confess yet another transgression to her therapist, decides to return it.

“The woman opened the wallet. Her physical relief at having it back coursed through Sasha in a warm rush, as if their bodies had fused. ‘Everything’s there, I swear,’ she said. ‘I didn’t even open it. It’s this problem I have, but I’m getting help. I just — please don’t tell. I’m hanging on by a thread.'”

“Goon Squad” is packed with scenes like this one, keeping you hooked when the cacophony of times, places, points of view, and characters threatens to overwhelm. Like strands of raffia wrapped around a bursting-at-the-seams scrapbook, the novel is loosely bound by time, the dread “goon squad” of the title. Teenagers lacerate their parents’ hypocrisies (Sasha’s daughter is allotted 78 pages for her PowerPoint presentation detailing her mother’s annoying habits), then reappear as parents of their own snarling kids. Parents are exposed as graying, thickening, incurably immature iterations of their teenage selves. Young rock stars grow old and irrelevant, then hip again: “Two generations of war and surveillance had left people craving the avatar of their own unease in the form of a lone, unsteady man on a slide guitar.” Time gets us all, Egan reminds us, tossing us into the quicksand pit of the past, hurling us over the cliff of the future, playing hard to get — and making pleasure hard to get — in the now.

Salon spoke to Egan about the dangers of making an uncommercial book, the decline of publishing, and how Obama changed the way we write about race.

“A Visit From the Goon Squad” is an idiosyncratic novel, to say the least.

I didn’t think of it as a novel, since it doesn’t fit within the commonly understood parameters of that genre. It’s obviously not a story collection, either.

Didn’t you get the memo? “Outside the genre” doesn’t sell.

It was scary, pouring time and energy into a project that didn’t have a clear genre identity and might therefore fall through the cracks. The economy had crashed since I’d published my last novel. I thought my publisher might say, “This isn’t the moment to publish an odd book.” Or that even if I sold the novel, it might come and go without a whisper.

And yet you wrote it genre-lessly.

There was a flipside to the fear. I’d never read anything quite like it, and that was exhilarating.

At first glance, I thought the 78-page PowerPoint presentation was gimmicky. But once I was immersed in the book, it worked.

I’m not an early adopter — I write by hand, for God’s sakes. But I became obsessed with PowerPoint when I realized that it had become a true narrative genre. It allowed me to represent gaps — pauses — in a tangible way that I couldn’t accomplish with a more traditional narrative. And “Goon Squad” is a story that happens in fits and starts, with a lot of the action transpiring offstage. You might say that discontinuity is the book’s organizing principle.

What were you reading while you were writing?

For mood and preoccupation, my model was Proust. “Goon Squad” is about time, and Proust is the grandmaster of that realm.

And what inspired the structure, such as it is?

“The Sopranos”! I wanted something that felt lateral and polyphonic like that show, with its multiple plotlines and drastic shifts in focus. I liked that peripheral characters suddenly become central — that shock of having their private lives suddenly open up. I wanted to encompass the whole spectrum, from tragedy to farce, in one book.

One of your characters, Bennie Salazar, is ethnically ambiguous. Despite his surname, you never make his racial background clear. Do you think the lightning rod of racial representation is less charged in the Obama era?

I hope so. I think Obama’s most helpful message on this subject is that we need to have the conversation instead of avoiding it. I’ve certainly been guilty of that avoidance, even though I’ve written about nonwhite characters before. Hell, in “The Keep,” I actually imagined a number of my characters as being black, but never said so — which of course left the impression that they were all white.

Recently I read an essay by Stanley Crouch, challenging literary writers to be less timid about crossing racial lines. I felt like he was speaking directly to me. I decided not to step around the issue again if it arose in my fiction. So I let Bennie be racially ambiguous, which seemed in keeping with his wishes. Bennie wanted to create himself anew, as so many Americans do.

You write a lot about men in “Goon Squad” and even more in “The Keep.” Do you find men more accessible than women, in literature and/or in life?

I write to escape from my life. Writing about men separates “me” from my work in a way that I find comforting.

Last I heard, you were married to a man.

[Laughs.] I guess my comfort zone as a writer is diametrically opposed to my comfort zone as a human being.

Actually, your books seem diametrically opposed to — or at least, quite disparate from — each other. And you practice journalism as well as fiction writing. Is lacking a recognizable identity as a writer on your list of authorial worries?

In a word, yes. Training readers to expect a voice or subject matter from me would interfere with the reinvention I crave. At the same time, I feel almost too able to disappear at times. It seems to be a function of my curiosity that I fade into whomever I’m listening to as a journalist, or writing about fictionally.

What does your therapist say about that?

[Laughs.] I grew up as a step-kid, always a little outside, always trying hard to follow and fit in. But over time I’ve come to feel that my tendency toward self-erasure is a deep and real part of me. I think I’d be this way no matter how I grew up.

The kind of writing I like to do involves throwing away what I’ve learned after each book and beginning something that takes place in a completely different world. I like the discomfort and excitement of having very little or no overlap between my new work and anything I’ve done before.

How much can a reader learn about the real you from reading your fiction?

I try not to think about my life as I work, but it trickles up through my fiction in ways I usually can’t see until later. I don’t want to see it. Which means that often the “me” character turns out to be the least sympathetic, because I’m fighting myself as I write.

What’s next?

I’ve been mulling over a historical novel for years. It’s about the post-World War II period, when Americans were absorbing their new status as citizens of a superpower. I’m especially fascinated by the divers who repaired ships. I love imagining what it felt like to be underwater in one of those big heavy suits.

Back to worrying — a big part of any writer’s life, especially nowadays, when rumors of the death of books might not be greatly exaggerated. Do you fret about the state of publishing while you work?

For me, writing is about maintaining the delusion that if I can nail the thing I’m working on, the world will be transformed. Obviously that’s nuts. But it’s a thrilling hallucination — and a big reason I love to write. So yes, I worry. But when I’m actually writing, I believe that all worries will be resolved.