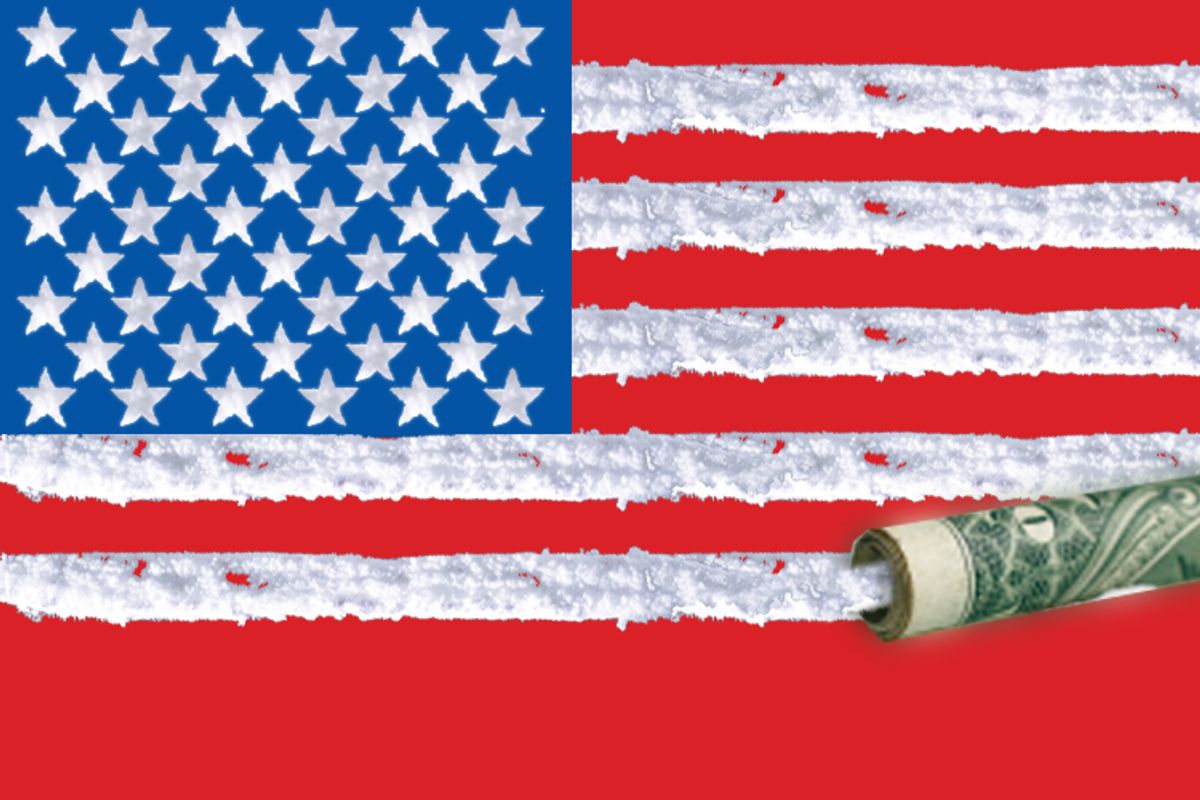

According to Tom Feiling, a London-based journalist and human rights organizer and the author of the new book "Cocaine Nation: How the White Trade Took Over the World," the best solution to America's cocaine problem is simple: make the drug legal. For many people, that's going to be a hard sell. While public perception about marijuana seems to be changing, cocaine still conjures up images of high-class leisure and rock star debauchery -- associations with wealth and luxury that makes any argument for legalization considerably more thorny.

But his book makes a persuasive case: Feiling speaks with coca farmers, police officers, government officials, producers and even doctors -- and emerges with a dire portrait of America's "War on Drugs" (a term the Obama administration has already jettisoned). The U.S. is set to spend $40 billion and arrest 1.5 million citizens this year in a policy that three-fourths of the county sees as misguided. Feiling uses an evenhanded and well-research approach to the subject. His case for legalization, he argues, stems from practical concerns: "It’s about more accountability, not less."

Salon talked with Feiling over the phone from London about the difference between cocaine and pot, the possible dangers of legalization, and the important lessons of "The Wire."

Marijuana-legalization efforts seem to be gaining steam in the United States. What about cocaine?

There are big differences. The campaign for decriminalizing marijuana is premised on medical marijuana, so they've found a medical use for what was until then a recreational drug. Cocaine does have medical uses, but not in the same way. And while there are a lot of recreational users, you also have a lot of problem cocaine users.

Cocaine is still seen as a recreational drug for the luxury class. It seems like there's a different kind of visceral reaction to the idea of legalizing cocaine.

One way to appeal to people whose gut instincts say this is a terrible idea, is to assert that this is about getting more control not less. Prohibitionists find it hard to accept that the law is not functioning as a deterrent; that it's not functioning at all. The idea that you can stamp it out is the real pipe dream. We're going to have to live with this stuff. So, are we going to regulate and control it, as we do with other dangerous substances, and dangerous activities? Or are we going to leave it in the hands of cartels or whoever is wealthy enough to buy a kilo of cocaine? What I'm proposing isn't an ideal; it's a pragmatic solution.

The book makes a strong case that the system in place is already extremely impractical.

I don't see how it could get worse. People who are unable to control their intake are getting their drugs on the street in adulterated forms from people who are armed, with no provision or any kind of service to help them address their problems or take their drugs safely, This is the worst possible way to treat substance abuse. In any other social policy field, these things are subject to assessment: We see if these policies are working. But in the "War on Drugs" there's an overarching moral imperative, so any cost-benefit analysis that you would apply to any system regulating a potentially dangerous subject is out the window.

You argue that the combination of poverty and drug use is really the powder keg that leads to urban blight and destroyed communities. But if you legalize drugs without eliminating poverty aren't we going to create a dangerous situation (like the "Hamsterdam" experiment in "The Wire," in which a police commander created a safe area for drug use, and it backfired)?

That's the distinction between legalization and decriminalization. "Hamsterdam" wasn't saying we're going to legalize the production and distribution of drugs; it was an example of not going after those who produce and distribute drugs outside the law, so you still have the same suspects. Legalization would be a situation where the same people who sell you 70-proof alcohol, or malt whiskey, those are the people who'd be selling you cocaine, perhaps with more stringent requirements for those who wanted access. I'm not suggesting we just leave off, and just let drug dealers sell their drugs.

If the drug trade were legalized in major drug-exporting countries like Mexico, Guinea Bissau, Jamaica and Colombia, wouldn't the drug profits and organization fall into the hands of pharmaceutical corporations?

Well, if we could start again, I think governments would realize that tobacco, for example, should never have been handed over to private corporations. And there are more and more restrictions on tobacco production and distribution now: You don't advertise it, you don't sponsor sporting events, we adulterate the product to make it less dangerous, we have well-funded programs to educate people on the danger of this stuff and we're making it harder and harder for tobacco companies to do their business. So perhaps in a future model for legal cocaine, production and supply would have this sort of middle ground.

Speaking of pharmaceuticals, there's little mention in the book of the abuse of legal, pharmaceutical drugs, some of which are becoming booming substitutes for cocaine.

As a British person with experience of Colombia, in those two countries, the mass abuse of legal drugs isn't as prevalent as I know it is in the States. But the phenomenon of the abuse of pharmaceutical drugs still leaves the questions I've tried to discuss in the book: What do you do with mass drug abuse? What do you do with all the problems driving it? Mental health problems, community breakdown, family, breakdown, unemployment, poverty, all these things.

The book does seem to downplay the effects of cocaine: "Take too much cocaine and you're likely to become dis-inhibited, grandiose impulsive, hyper vigilant." That almost sounds like drinking a cup of coffee.

I hope I've made plain the dangers of it. People have learned the hard way just how awful a drug like crack and powdered cocaine can be. But let's ask the question: Why do some people get into a problem with it and some people don't? Take whiskey -- that stuff can kill you. It regularly does. British hospitals are full of people who are on the verge of death from drinking too much. So perhaps I'm being a bit polemical in saying that you at least have to make the distinction, which is lost on prohibitionists, between problematic and unproblematic use.

Have you encountered any seemingly unlikely critics or supporters thus far?

The whole critique of prohibition is not really a left-right issue, is it? We get allies from all sides. It is interesting that a lot of right-wingers are against the "War on Drugs," and more likely to question prohibition. The Libertarians in the States are keen on criticizing the "War on Drugs," but they don't acknowledge the problem of mass drug addiction and abuse. That's the big question: What to do about mass, chronic drug abuse? One of the criticisms was: "This book almost celebrates drug traffickers." I think anyone making the argument that I am runs a risk of hearing that you're downplaying the problems. I've tried to tread carefully.

I think it is about treading carefully. For example, "The Wire," which you mention a lot, avoids glamorizing the drug trade.

Yeah, when I was really hunkering down writing the book, I'd always knock off and watch a couple of episodes of "The Wire."

That's doesn't really sound like a break.

(Laughs) That was my idea of a break.

Shares