Few people some 20 years ago, near the start of the administration of George Bush Sr. — when cyberpunk was still a fresh notion, when there existed only three "Star Wars" films, all good, and when the word "steampunk" had only just been coined — would have predicted that in the early 21st century some of the most entertaining and deftly rendered science fiction being currently published would derive from the pen of a Frenchman dead for a century, whose legacy had long been set in cement as amounting to nothing more than ham-handed adventure novels for juveniles. And yet at that distant time, the rediscovery of this Gallic genius was actually well under way, and today his stature is almost completely restored to its former glory.

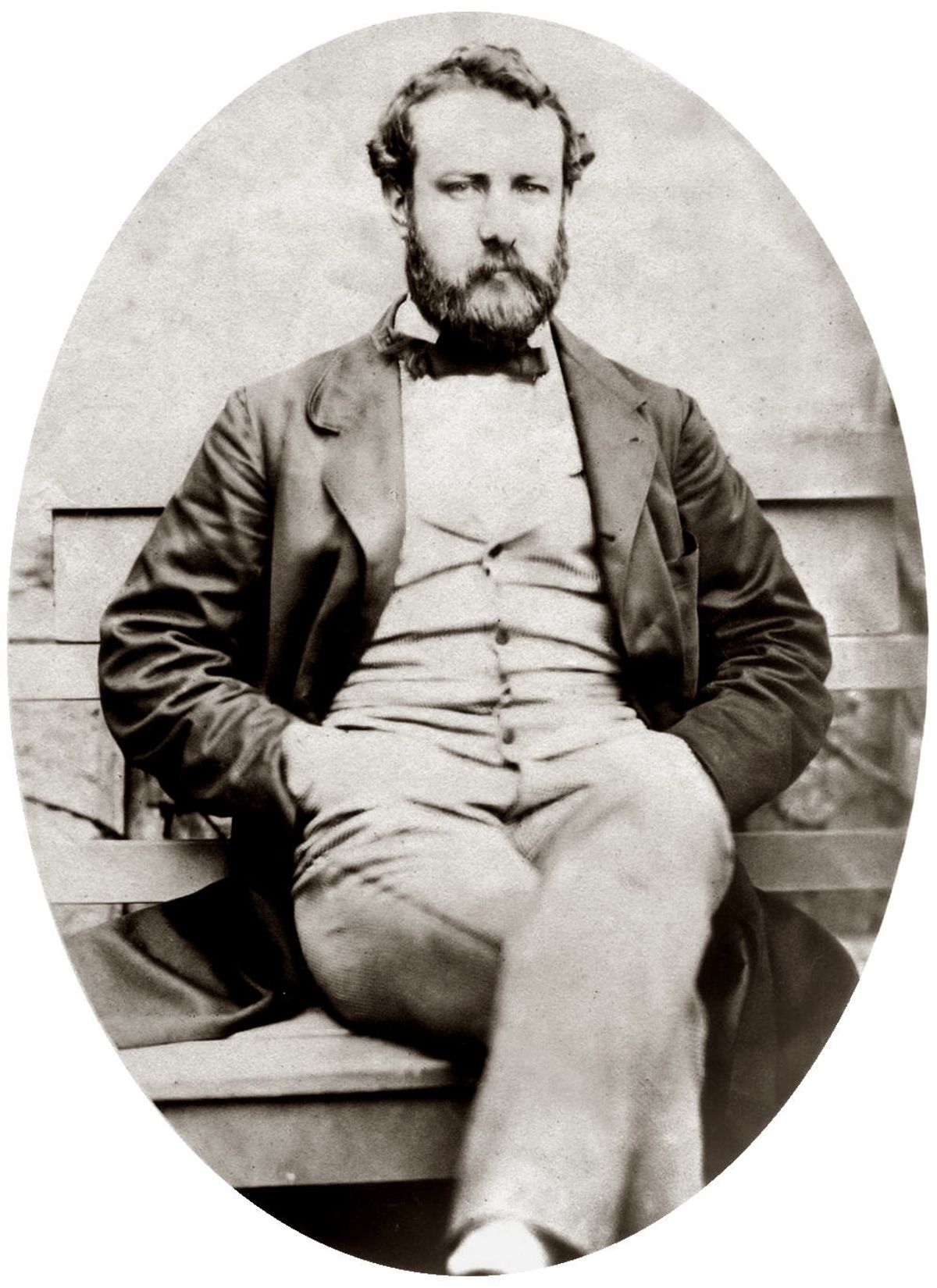

The author under discussion, as you might well guess, is none other than Jules Verne, one of the two generally acknowledged fathers of the science fiction genre, along with his co-daddy, H. G. Wells. Recent years have seen a flood of "new" Verne titles, including re-translations of familiar classics ("The Mysterious Island"), first-time English versions of lesser-known novels ("The Kip Brothers"), and even heretofore-lost manuscripts brought to light ("Paris in the Twentieth Century"). Taken as a whole, this mass of Verniana has encouraged a reassessment of the writer's career among scholars and critics, as well as providing real pleasures for the average reader and fan.

The author under discussion, as you might well guess, is none other than Jules Verne, one of the two generally acknowledged fathers of the science fiction genre, along with his co-daddy, H. G. Wells. Recent years have seen a flood of "new" Verne titles, including re-translations of familiar classics ("The Mysterious Island"), first-time English versions of lesser-known novels ("The Kip Brothers"), and even heretofore-lost manuscripts brought to light ("Paris in the Twentieth Century"). Taken as a whole, this mass of Verniana has encouraged a reassessment of the writer's career among scholars and critics, as well as providing real pleasures for the average reader and fan.

My own reawakened interest in a figure I had long ago stuffed into his unfairly assigned pigeonhole stems from my attendance in 2004 at the Utopiales Festival held yearly in Nantes, Verne's hometown. There a handful of guests were given a generous and highly educational tour of the official Verne archives that hold almost 100 of his extant manuscripts. This focus on Verne's craft and accomplishments primed me to appreciate the new editions when I encountered them: a raft of reissues as entertaining as they are scholarly and lovingly translated.

Credit for kicking off the English-speaking world's recalibration of Verne should go to Walter James Miller, a professor at NYU whose efforts along these lines began in the far-off year of 1965, with his essay "Jules Verne in America: A Translator's Preface." This piece famously exposed the No. 1 rotting albatross fastened to poor Verne's neck: inexpert translations. For instance, Verne's original straightforward geographical reference in one book to the "Badlands of Nebraska" emerged through the boneheaded efforts of such early interpreters as W.H.G. Kingston as "the disagreeable territories of Nebraska." And in his notes to "The Begum's Millions," scholar Peter Schulman gives the example of how Verne's fanciful metaphor of Paris as a competitive social arena somehow got turned around via bad anonymous translation into a depiction of the protagonist as a professional wrestler!

Aside from inexcusably moronic infelicities, Verne's works in English were also plagued with unauthorized cuts and interpolations that had the cumulative effect of simplifying the textual complexities and controversies. No wonder publishers began to market the books solely as adventures for boys. And lastly, Verne suffered from the cack-handed ministrations of his heirs: His final bequest of posthumous titles were shamelessly recast to their detriment by his son Michel, further sullying the father's legacy.

The latest installment in the restoration of Jules Verne is, admittedly, one of his lesser late-period works: "Le Chateau des Carpathes" from 1893, usually presented in English as "The Carpathian Castle", but in this incarnation offered as "The Castle in Transylvania" — possibly with a somewhat commercial eye toward luring all lovers of things vampiric.

And with some justification, since this book is an illuminating rarity among Verne's output, a Gothic-steeped romance whose scientific aspects are kept hidden till the climax. And so, yes, we have here Verne's very own pioneering entry in what the invaluable TV Tropes website identifies as the "Scooby Doo Hoax" mode of storytelling: "The characters investigate a site with reported paranormal activity. By the end of the episode, they discover that the supposed supernatural activity is nothing but an elaborate hoax taking advantage of local lore to frighten off the curious from discovering and interfering with their main criminal activity." Verne's villain even manages to satisfy the "You Meddling Kids" trope well known to fans of Scooby and Shaggy's adventures: "And I would have gotten away with it, too, if it weren't for you meddling kids!"

Chalk up another visionary accomplishment for the Sage of Amiens! What a television scripter he would have made!

Before delving into the story of "The Castle in Transylvania," let us pay homage to the fine new translation by the experienced and talented Charlotte Mandell.

My battered Ace paperback of "The Carpathian Castle" from 1963 opens with this line: "This story is not fantastic; it is simply romantic and nobody would think of classifying it as legendary." Mandell offers: "This story is not fantastic; it is only romantic." So far, so close. But then the 1963 version begrudges us merely two more prosaic sentences prior to launching the plot. Mandell, however, gives us an almost postmodern observation: "We are living in a time when anything can happen — one can almost say, when everything has happened." Then follows the restoration of one of Verne's charming info-dumps, nearly a page's worth, on the myths of Transylvania, before reaching the same jumping-off point of the story's real-time action.

This creative upgrade in the quality of the prose and fidelity to the original text persists throughout the novel and sets high standards for the reader's enjoyment.

Now, what of Verne's tale itself?

We are in the small mountain village of Werst, where a castle, abandoned for 20 years, broods from on high. No one visits the decrepit yet sturdy place, for fear of spooks and in reverence toward the last owner, Baron Rudolf of Gortz, who left the region under mysterious circumstances. But then a shepherd spots smoke coming from the castle, and the village goes into a panic. Plainly, the devil has taken up habitation there! A local skeptic, handsome young Nic Deck, volunteers to investigate. He co-opts Dr. Patak as his partner. Patak, previously a bold unbeliever (at least in conversation), is now revealed in the face of the unknown to be cowardly. But pride forces him not to back down.

At the castle, supernatural manifestations occur, Nic is shocked insensible, and the investigators are forced to retreat. At this point, Verne makes an unexpected lateral move. A visitor to the village arrives by chance, one Count Franz of Telek, accompanied by his loyal manservant. We get Franz's back story, which involves a doomed love affair with an opera singer — a woman who was literally frightened to death by none other than the creepy Baron Rudolf of Gortz and his sinister henchman, the Faustian Orfanik! Learning this, Franz of course vows to solve the mystery of the castle, or die trying. He discovers Gortz and Orfanik in hiding — really up to nothing more evil than having a good morbid pity party and trying out a few cutting-edge electrical inventions on the medieval townsfolk — before the whole place gets blown up in a suicide move by Gortz.

This simplistic plot, predictable by even the most naive reader of 2010, was probably no big surprise even to the "Castle of Otranto"-savvy Gothic fan of 1893. Nonetheless, Verne's tale remains compulsively readable for a number of reasons.

First is the craftsmanship. After so many books, the 65-year-old author was an expert at pacing, characterization and scene-setting. His villagers are all as solid and utilitarian as firewood, yet a gentle mocking humor pervades. He ladles in just enough of his customary background detail — cultural, scientific, geological, historical — to render everything plausible and tactile. Moreover, there is a real manifestation of Verne's love of the natural world here, in his lush descriptions of the forests surrounding Wertz.

The reader can also take pleasure in the cleverly contrasting natures of the three sets of protagonists. Nic Deck and Dr. Patak represent the unsophisticated, clownish but earnest peasants, living remnants of a fading age. Franz and his servant stand for urban sophistication, wiser but still limited. And Gortz and Orfanik are doomed scientific seekers after hidden knowledge, advancing civilization even through base and selfish motives. The interplay among these three paradigms provides plenty of complexity.

Verne's handling of a love affair is, for him, anomalous and intriguing. A biography of the author by his niece speculates about a secret love affair occurring around this time. But whatever the real-world impetus, the story prefigures the then-unwritten "The Phantom of the Opera" in fascinating ways.

But the essential science-fictional aspect of the book lies in its clash of cultures. The theme of a superior outside power deranging the isolation of an obsolescent backward enclave is prime SF matter — see Samuel R. Delany's archetypal "We, in Some Strange Power's Employ, Move on a Rigorous Line." In the end, "The Castle in Transylvania" stands as an example of Verne at his most pleasurable and educational, exploring the remarkable reality of our simultaneous technological plummet and ascent.

Shares