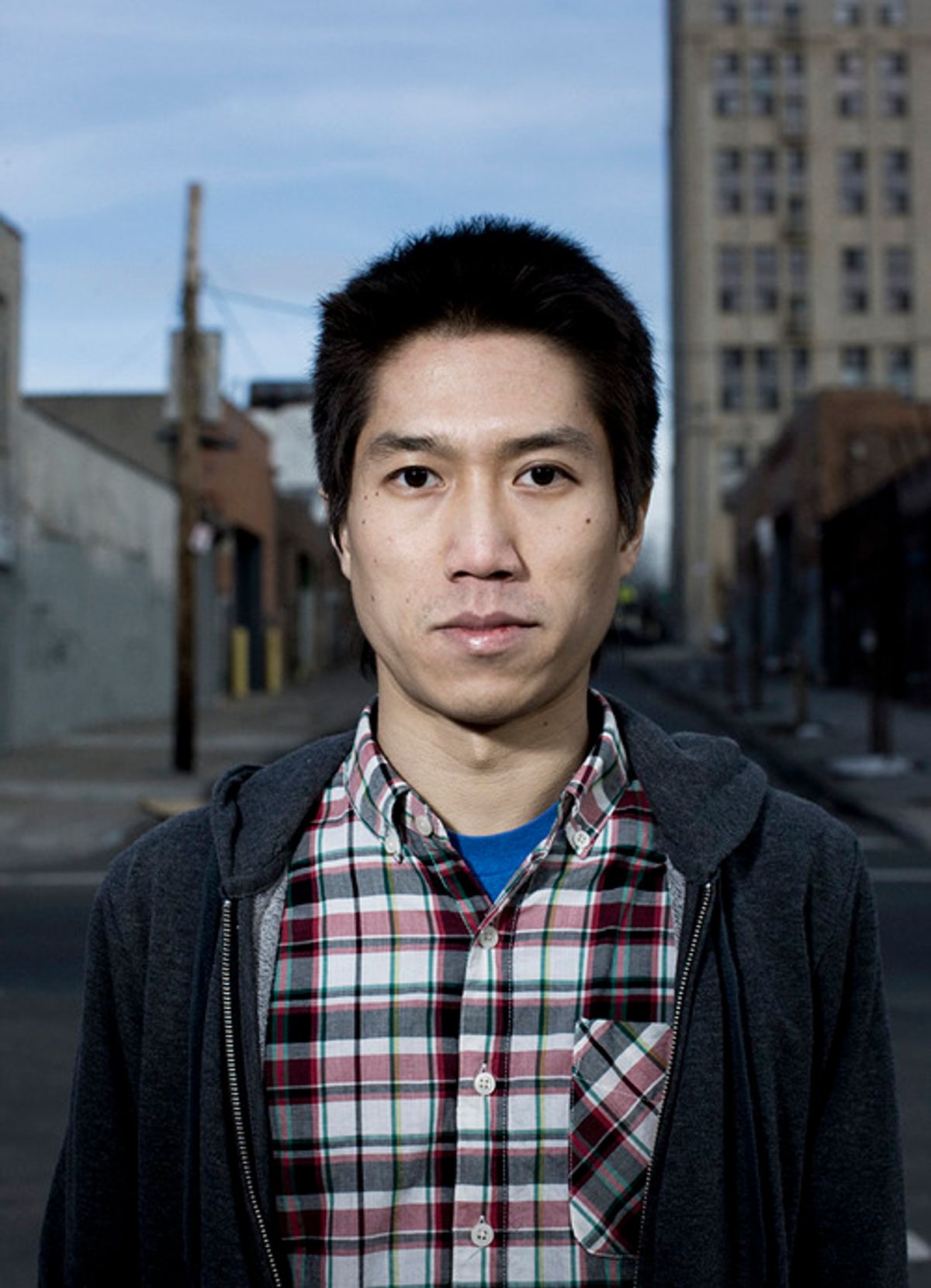

Tao Lin is the next big thing in urban hipster lit. At least, so say the people that read his books on the subway. "That guy is the next big thing," announced one last fall to a stranger eyeing his book. "People just don't know it yet."

The book he showed off was "Shoplifting From American Apparel," the novella by 26-year-old Brooklyn, N.Y., author Tao Lin. Of course this exchange happened on the L train, which moves through the heart of hipster Brooklyn, and of course the guy was wearing Converse Chucks, skinny jeans and a tight flannel shirt with the sleeves rolled up. He looked about 27.

"Shoplifting" was Lin's fifth major published work, but with it he pushed himself closer to mainstream recognition than ever before. For years, Lin wrote for small literary magazines and online outlets like the Nervous Breakdown, NOON and 3:AM. His earlier collections of poetry and stories, published by the independent press Melville House, went generally unnoticed, though championed by bloggers here and there. In 2008, he earned some infamy when Gawker posted about his annoying promotional tactics. And finally, in January 2009, New York magazine's book critic Sam Anderson christened Lin the "New Lit Boy," though he nonetheless acknowledged, "It's tempting, from a distance, to dismiss him." As the Sept. 7 release of his new book, "Richard Yates," approaches, Lin once again garnered Gawker headlines -- and annoyed scores of commenters -- thanks to his trespassing arrest at the NYU bookstore in lower Manhattan.

Through all of this, Lin's writing, despite its shortcomings, has perfectly captured the aimless malaise of the Internet generation. It's no wonder, then, that he has successfully used the Web to manage his career and push his name onto computer screens everywhere. His guerrilla-style online marketing has made him a Web phenomenon. But can it break him into the publishing mainstream?

What fame Lin has already achieved is a testament to his ability to master viral and unconventional publicity techniques. In July 2008, Lin sold six shares of "Richard Yates" online. The winning bidders gave him $2,000 each in exchange for 10 percent of the domestic profits that come from "Yates." As he says with a laugh, "If it doesn't make very much, that's their loss." Inevitably, Stephen Elliott's Lin-adoring online outlet the Rumpus named "Richard Yates" the August selection for its newly launched book club, four months before the book's publication. James Frey has endorsed "Yates," and the New York Observer recently published a profile of Lin written in his own distinctive style.

In early November 2009, Lin held an "experimental contest" on his blog that invited users to bid a certain amount of money via Paypal -- any amount they chose -- on a prize package of Tao Lin goodies. The catch: Lin's prizes would go to the highest bidder, but entrants would not get their money back if their bid lost. Lin posted a video that showed off the prizes: A "unique drawing of a Sasquatch holding a hamburger," which he notes has the "crying hamster stamp of authenticity" (a small doodle Lin puts on all his artwork and also signs books with); a Tao Lin T-shirt; an unpublished draft of a short story; an error-filled galley copy of "Shoplifting From American Apparel"; and a small Moleskine journal filled with Lin's notes. "You can find out exactly what I do by getting this and looking at my to-do list," he declares in the video. One finds all of this thoroughly ridiculous until learning that the last Moleskine notebook he sold on eBay went for $80. He is making real money off of this shwag. Lin says, "I probably make $700 a month from selling stupid things on my blog."

Beyond raising funds and buzz for his antics -- and unlike the majority of successful novelists -- Lin is also willing to use the Web as a tool for engaging with his readers directly. In a recent HTMLGIANT comment thread, someone under the user name "Attractive skinny girl" asked Lin for his phone number. He posted it, no hesitation. The average fiction lover can't just shoot John Irving an e-mail, or friend request Martin Amis on Facebook. They can, however, contact Tao Lin quite easily, and in most cases he'll respond.

And then there's Lin's writing, which aims to capture the aimlessness and tedium of today's Web-obsessed 20-somethings:

Sam woke around 3:30 p.m. and saw no emails from Sheila. He made a smoothie. He lay on his bed and stared at his computer screen … About an hour later it was dark outside. Sam ate cereal with soymilk. He put things on eBay then tried to guess the password to Sheila's email account, not thinking he would be successful, and not being successful.

This is the opening passage of "Shoplifting From American Apparel." To many, the style is stark, lifeless and lazy. But not to Lin's fans. "I like the dreamlike quality," says Jim Whitten, a teacher from Connecticut. "There are no real transitions. I like how minimal it is." Sayid Edwards, a recent Wesleyan graduate, chimes in: "It's like, have you ever been in a conversation with someone who doesn't say very much? And you're intrigued by it, but you're also kind of annoyed." High praise, indeed.

In mid-November, Lin read at Book Thug Nation, a tiny used bookstore in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Hassan Abudu, who came to New York from Ghana and works as an online media consultant, commented afterward: "One thing I've come to wonder since being in NYC is, why are we all so depressed?" This may be the most apt thing someone could say in relation to Tao Lin's writing. If Lin isn't actually sad, he's a damn good actor. He once told me, "I'll probably kill myself before I'm 40." Was he kidding? "Just sort of."

Abudu's term, "depression," is a bit too clinical in this context. Where Lin is coming from, and what his readers share, is a sense of loneliness. The malaise is not specific to New York, of course, but it is typical of a certain ilk of detached 20-somethings across the country.

The loneliness could be attributed to the Internet. Lin and his literary peers spend hours and hours online, and although doing so fosters a sense of connectedness, it is equally isolating. No matter how many fans or fellow writers Lin "meets" online, at the end of the day it's still him, sitting at his laptop alone. Any moments of delight or engagement that the Internet prompts are separated by longer stretches of boredom, as implied by the title of a short story by Brandon Scott Gorrell, a member of Lin's online literary gang. The story is called "Minimizing and Maximizing Mozilla Firefox Repeatedly."

Even an angry Amazon.com reviewer "Visa Dimo Kogan," in a review of "Shoplifting," admits: "He's accurate in his portrayal of the apathetic, technological, and depressing generation that I'm sadly a part of," though the review continues, "If this is the literature of our generation, then I'd rather die in a car crash." This is met with a single, symbolic response from another reviewer, Jesse Vaughan: "Better buckle up, bro."

Vaughan's tersely funny defense is representative of the Tao Lin faithful. Lin's readers come to his aid on message boards and blogs all over the Web because they feel that for better or worse, his books represent the moment. They share his loneliness. Time spent on the Web remains a solitary act. And while New York City cannot be credited with the invention of young angst, it does serve as a city metaphor for the Internet. It's urban loneliness, and Lin has captured it for his readers.

On the night before last Halloween, Lin read at the Center for Performance Research on New York's Lower East Side. Out in the lobby after the event, he leaned against a wall with a bottle of Brooklyn Lager, drinking in the scene around him. It was brief, awkward respite from the realm in which he's most comfortable: sitting at his computer. One could imagine what happened next. Shortly after the reading, he left the event without fanfare, then hurried home to connect with those readers who hunger for his presence and voice.

Daniel B. Roberts is a newspaper reporter and pop culture blogger. He works in the Bronx and lives in Manhattan. You can find him on Twitter.

Shares