During its 70-year lifetime, the Soviet Union was the perfect Other for Westerners: a colossal enigma, alternately dystopian and utopian, onto which we could project all our fears, hopes and dreams; a funhouse mirror in which our own culture was reflected in amusingly warped fashion; an outré parallel continuum from which bizarre messages trickled out at irregular intervals, bearing cryptic hints of off-kilter wonders, quotidian strangeness and kludgy tech. The Iron Curtain was no mere metaphor, but rather an imposing information barrier like the force field around Coventry, Robert Heinlein's land of dissidents, rogue ideologues, criminals and nonconformists.

In this ancient era, science fiction readers and writers had some vague notion that the speculative literature of the Soviet Union represented a bracingly alternate family of narratives, a non-Anglo, non-Euro, non-North American, non-Latin American tradition of proleptic storytelling that sprang from an alien lineage of fabulism.

In this ancient era, science fiction readers and writers had some vague notion that the speculative literature of the Soviet Union represented a bracingly alternate family of narratives, a non-Anglo, non-Euro, non-North American, non-Latin American tradition of proleptic storytelling that sprang from an alien lineage of fabulism.

But solid examples of actual SF from the Communist Bloc were sparse on the ground. A few pioneering anthologies cropped up. Isaac Asimov, himself of Russian birth, introduced "Soviet Science Fiction" and "More Soviet Science Fiction," both appearing in 1962; "Path Into the Unknown," "Last Door to Aiya" and "The Ultimate Threshold" followed over the next eight years. Meanwhile, a few individual authors, such as Stanislaw Lem and the Strugatsky brothers, were plucked by Western translators like beet chunks from the Soviet borscht.

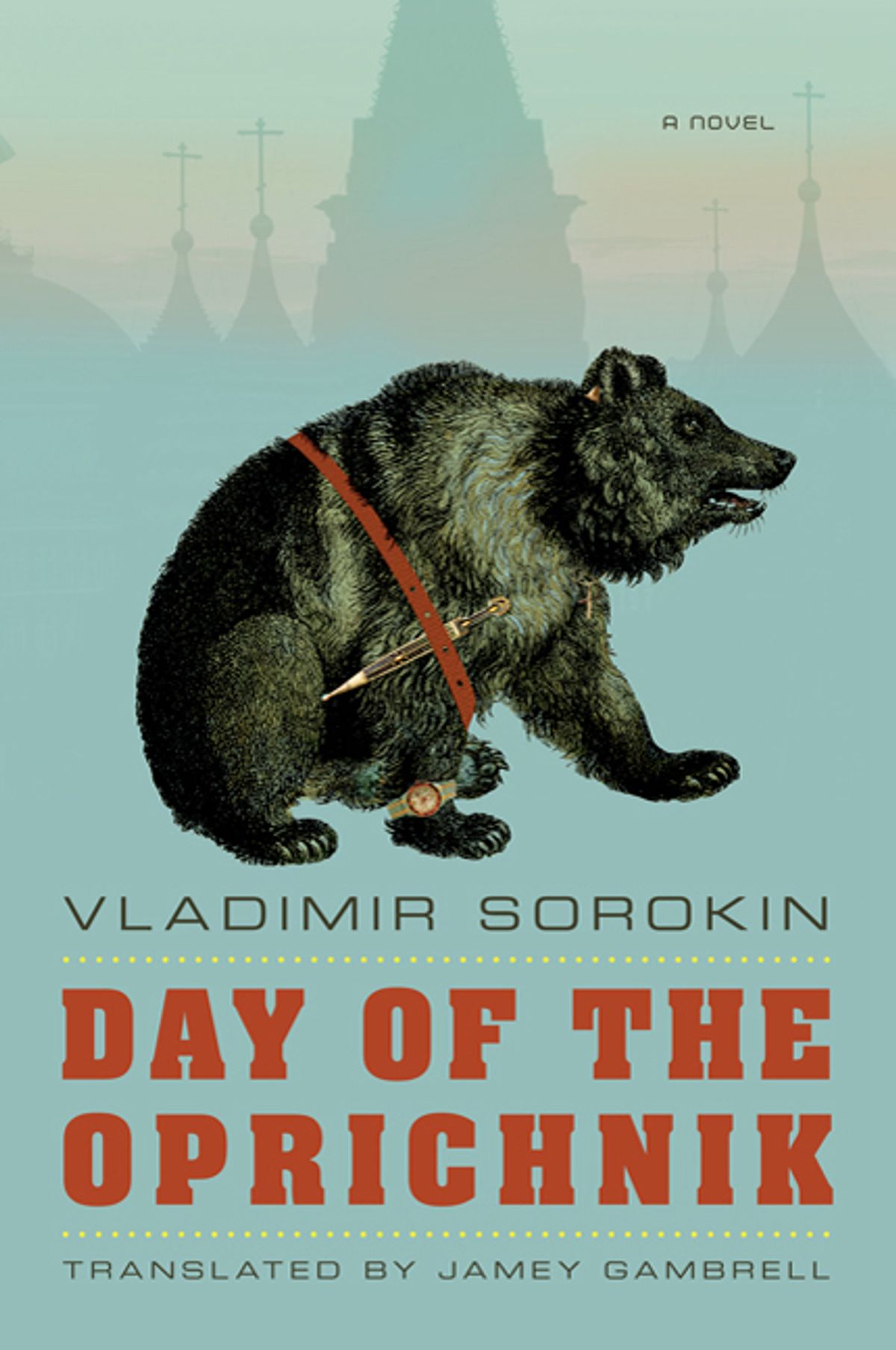

Just when it seemed as if Soviet SF might be gaining a faltering foothold in the consciousness of Western readers, the political empire collapsed, taking the Soviet cultural superstructure with it. Since 1992, interest in -- and access to -- translated SF from Russia and other ex-Bloc countries seems to have fallen nearly to pre-1962 levels. Only the novels of Victor Pelevin ("The Life of Insects") and Sergey Lukyanenko ("Night Watch") appear to have made even a dent in American perceptions. Now, with the publication of two new translations of the remarkable work of Russian satirist Vladimir Sorokin -- jaunty, despairing, cynical, hopeful, traditional and postmodern by turns -- an even more explosive impact seems likely.

In his native country, Sorokin -- born 1955 -- is a figure of controversy and admiration, even occasionally spawning public protests against his bold and irreverent fiction, which was of course mostly suppressed under Communist rule. Reading his newest work, "Day of the Oprichnik," part of a concerted publishing effort to introduce him to English-speaking readers, one encounters a Swiftian writer steeped in globally shared images out of science fiction, but whose sensibility is deeply rooted in Russian culture.

In "Oprichnik," it's the year 2028, and Russia has reinstated the Tsar and the royal family, withdrawn from contact with the West behind new barriers, ceded Siberia to the Chinese in exchange for favorable trade conditions, and, most crucially for our story, instituted a new internal security elite called the "oprichniks," of whom our narrator, Komiaga, is one. Given a free hand to repress dissent, the oprichniks have become a decadent pseudo-SS given to graft and self-indulgence, hypocritically masquerading under the guise of a monastic piety. As we follow Komiaga through the frenetic course of 24 jam-packed hours of brutality, venality, political chicanery and blind absurdism, we watch a country willfully plunge back into the worst excesses and injustices of the 19th century, while maintaining a postmodern, technocratic veneer. The oprichniks drive autonomous "Mercedovs," get their news from holographic "bubbles" and employ ray guns and lasers in their depradations -- as well as the old-fashioned torture rack and knives. The blend of antique and futuristic creates a fascinating literary estrangement, as well as symbolically representing our current global dilemma: tied between retrograde and forward-facing horses of stasis and change.

The brilliant self-delivered portrait of Komiaga and his crowd is an achievement on a par with Ray Bradbury's "Fahrenheit 451," a book that is certainly the model for "Oprichnik." In fact, a literal book-burning scene occurs in subtle fashion at one point, as if in homage to the classic Bradbury text. As with "Fahrenheit," the transvaluation of values is so massively and convincingly portrayed that the topsy-turvy world of future Russia begins to assume a nightmare substantiality equal to our current milieu, casting its unborn shadow threateningly backward in time.

Sorokin delights in an Orwellian buggering of language, even italicizing the worst perversions of speech. For instance, lighting a blacklisted nobleman's house on fire is called bringing in "His Majesty's red rooster," while raping the wife of the disgraced man is "the way it's usually done." The oprichniks achieve a leering self-justification through such linguistic hypnosis.

But Sorokin also dazzles with sheer science-fictional wordplay, along the lines of Lem in his "The Futurological Congress." The section describing the sanctioned audio-video channels for tame dissidents is one such passage, reveling in babble such as "the behavioral model of Sugary Buratino, and medhermeutical adultery ..." Likewise, Sorokin nods to famous SF works: A scene where the torturers ingest drugs via living fish injected into their veins recalls both Rudy Rucker's drug Merge and Jeff Noon's psychedelic feathers in Vurt. And who are some infamous enemies of the state? None other than "the cyberpunks."

It would be wrong to give the impression that this book is gray and grim. Despite all its too-plausible horrors, it remains a rollicking roller coaster of a tale, compulsively, LOL-ishly readable (the climactic gay oprichnik orgy is a tour de farce), full of unrepentant rude life force, much like Norman Spinrad's classic faux-Nazi fantasy "The Iron Dream," a debauched fever fugue featuring a womb-crazed return to some fairy tale past -- and resembling, to our Western chagrin, a Tea Party convention where attendees dress like the Founding Fathers and spout reactionary bile.

Sorokin's "Ice Trilogy," here translated piquantly by Jamey Gambrell, who also handled "Oprichnik," was originally published in three parts from 2002 to 2005. It's a Cossack of a different regiment entirely, with each installment displaying a contrasting storm of weirdness that add up to a cumulative gonzo hurricane.

Part 1, "Bro," starts out like an old-fashioned Tolstoyan bildungsroman. We are introduced to Alexander Snegirev, born in the year 1908 to a well-off family. From birth he's an oddball, not fitting in, although he tries to play a part in the tumultuous history of the next 20 years. The naturalistic gravitas of this early section convinces you you're reading a straight historical novel, and grounds the subsequent fantasy with deep roots. For when Snegirev tracks down the Tunguska meteorite that fell coincident with his birth (on an expedition that plays out like Kurosawa's "Dersu Uzala"), his life veers off the rails. Touching the alien "ice," he receives a revelation: He is one of an elite cohort, some 23,000 souls, nescient fallen angels trapped in mortal clay. His real name is "Bro," and his mission is to reassemble his tribe prior to Armageddon.

The rest of "Bro" reads as if Kurt Vonnegut, Doris Lessing and Thomas Pynchon had rescripted Hammer Films' cult classic "Five Million Years to Earth," after mainlining Robert Heinlein's "Stranger in a Strange Land." It's a Gnostic odyssey down familiar 20th-century history rendered utterly Martian by Bro's perspective and insider knowledge. His death by natural causes at the end of WWII culminates the first book.

Part 2, "Ice," immediately throws us for a loop. As with most middle volumes of any trilogy, it's somewhat protracted and bridgelike. The book opens in contemporary times, and Bro's recruiters are still active, continuing to search out the missing 23,000. But the conspirators seem to have devolved somehow from the plateau of Bro's nobility, becoming more violent and meaner, heedless of the "meat machines" (all the humans other than the chosen Brotherhood of Light). In stripped-down, punkish prose, Sorokin offers some Russian mob doings (gangsters have become entangled in the Tunguska ice trade) and details post-WWII Brotherhood history through the eyes of a woman named Khram, the new leader of the fallen angels. We end this installment with the appearance of a young boy who seems destined for large things.

Part 3, "23,000," confounds our expectations again by following immediately upon the last sentence of its predecessor. The mysterious boy is kidnapped by the Brotherhood, subjected to the awakening initiation, and christened Gorn. He is instrumental in the completion of the sect's century-old quest, a denouement for which Sorokin pulls out all the outrageous stops, masterfully employing two new human viewpoint characters, Olga and Bjorn, whose lives have brushed up against the Brotherhood in the past. Brashly and shamelessly, the author even manages to redeem what amounts to the biggest SF cliché of all times, the "Adam and Eve" New Genesis ending.

Amid all this apocalyptic adventuring, the "Ice Trilogy" provides a surprisingly trenchant examination of all cults and belief systems and nascent religions, from Mormonism to Jonestown, Scientology to Mayan 2012 Eschatology. There's a comic-book quality to much of the action (consider how close Sorokin's story is to that of the X-Men and their Cerebro scanning device that seeks out mutants), but Sorokin uses it to frame genuine philosophical debates about serious ontological conundrums. Ultimately, his trilogy delves with great subtlety into the idea of a life powered by mystical rapture -- a notion whose fascinations and dangers require no translation.

Shares