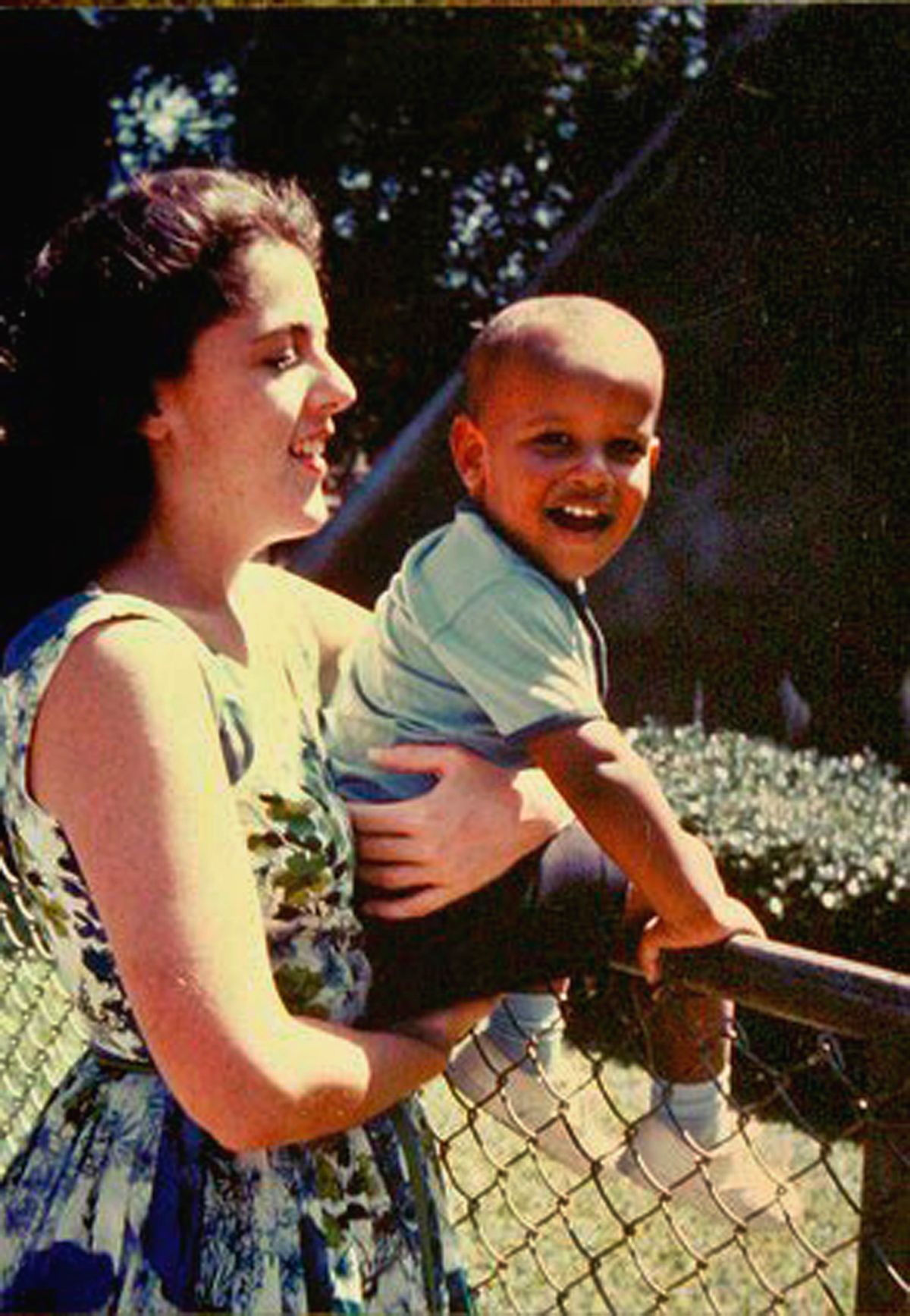

The story begins, as it does for every person in the world, with his mother. For Barack Obama, it's about a seemingly all-American girl from Kansas, Stanley Ann Dunham. But what it became was a very different -- and distinctly modern -- kind of all-American story, a multicultural adventure that would lead a little boy with a peripatetic, twice-married mom to become the first African-American president of the United States.

In the New York Times' excerpt of "A Singular Woman: The Untold Story of Barack Obama's Mother," author Janny Scott reveals how the man who wrote "Dreams From My Father" was shaped by the adventurous, ambitious, imperfect lady who bore him. It's a tantalizing slice of what will likely become one of the most talked about books of the spring, and a compelling portrait of a woman whose unorthodox life would make for a compelling read even if her only son hadn't become the 44th president.

Scott's narrative illuminates Obama's youth from the point of view of its leading lady, in a story of blended families, mixed races, and varied cultures that stretches across the globe. He had an absentee Kenyan father and a Hawaiian babyhood. He had an Indonesian stepfather and half-sister. He lived among other languages and religions, listening to "the sound of the Muslim call to prayer" in Jakarta and attending at one point a Catholic school. He was the boy who had rocks thrown at him for being different, who along the way would pick up something of all his influences and environments in the formation of his character. A friend of his mother describes him as having "the manners of Asians and the ways of Americans -- being halus, being patient, calm, a good listener. If you’re not a good listener in Indonesia, you’d better leave." And he got all that -- the good and the bad and the difficult and the amazing -- because of his mother.

Obama's is not the old-fashioned, Clintonesque story of the small town kid who made good, nor is he that other old-fashioned tale, of the young lion from a Kennedy or Bush political dynasty. He is a new -- and increasingly more common -- 21st-century boy. The knee-jerk disdain so many of his critics have for him can be traced largely to his worldliness: He's a man who, of necessity, was brought up not to be Joe the Plumber but a citizen of the planet.

Obama's mother, who died in 1995, has been, up to this point, largely a shadowy figure in his narrative. She's been portrayed as a quiet girl swept up in an exotic life, a woman who made the seemingly unthinkable choice to send her 10-year-old son far away to live with his grandparents so he could get a better education. Yet Scott's account reveals her as another kind of familiar American archetype: She's the girl who ran away. Every town has one -- the one whose personality and curiosity are too big to stay in one place, who eternally fascinates everyone she left behind.

Dunham was the smart girl who sacrificed for her family but who stayed true to her own ambitions, who married the men she loved even when cultural taboos stacked the deck against them. She went to school and made a career for herself, making her a powerful example of how strong, working mothers can raise strong men. She told her daughter "not to be such a wimp." And though she surely had pains and regrets, she told her son, "If nothing else, I gave you an interesting life." Clearly, it often wasn't easy, for either Dunham or her son. But Scott's narrative shows that an interesting life is a priceless thing. It's not just one of the greatest gifts a mother can offer her child -- it's one of the best she can hope for herself.

Shares