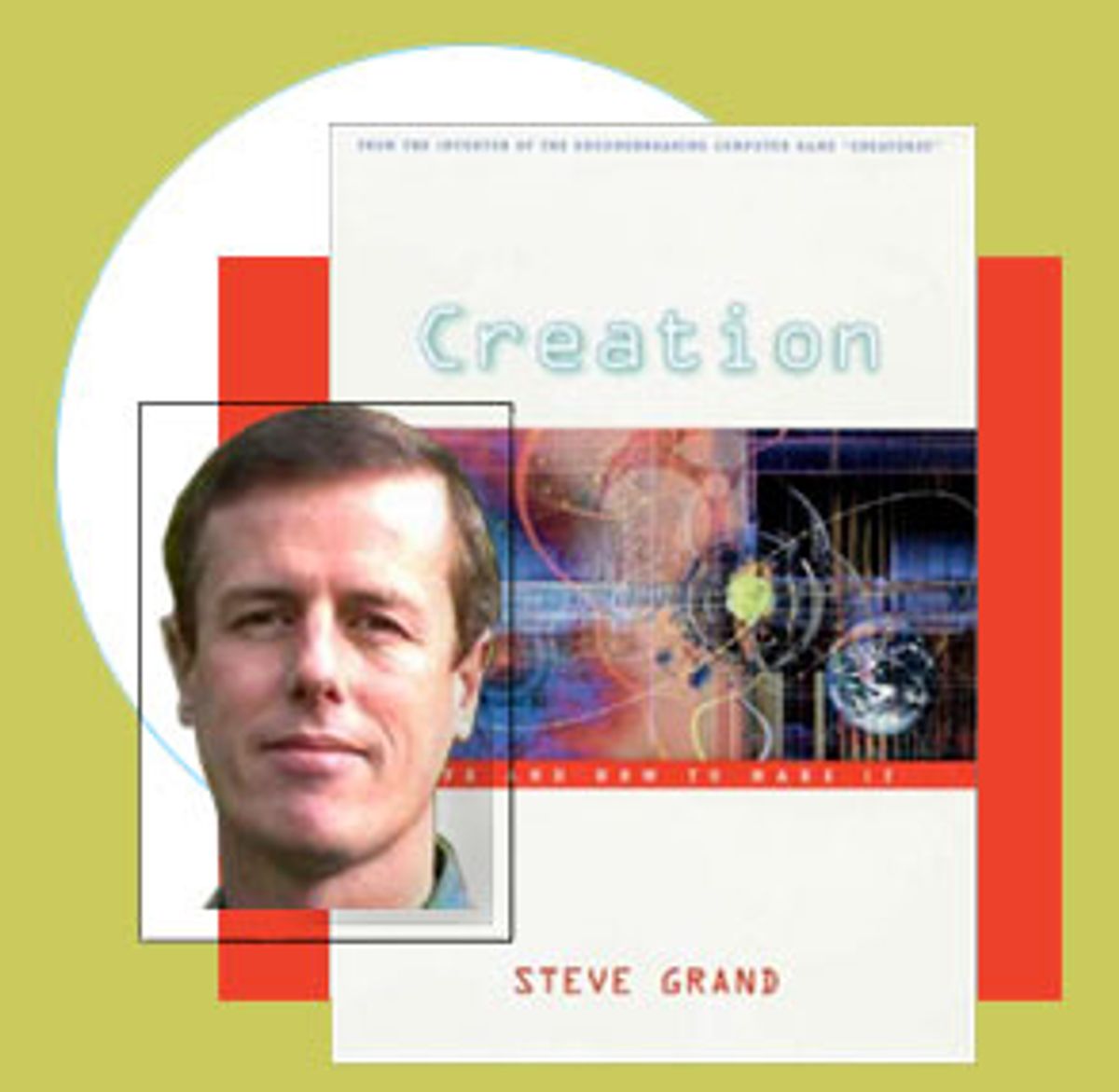

When Steve Grand developed his artificial-life computer game Creatures nine years ago, he never dreamed that 1 million people would play it and come to care deeply about the lives of their virtual pets. Creatures allowed players to design these pets, or norns, and observe how they interacted with their environment and with other norns. The norns have computer-simulated hormones and DNA. They eat and breed. They fall in love. According to Grand's book "Creation: Life and How to Make it," "Creatures was probably the closest thing there has been to a new form of life on this planet in four billion years."

That's a pretty startling claim, but as Grand explains in his strangely accessible and consistently surprising book, whether or not you believe it depends on your definition of what's alive. Grand -- now two years into building a 4-month-old robot orangutan named Lucy -- argues that our traditional notion of life is just now beginning to change.

Grand spoke to Salon from his home outside of Bristol, England (where he works out of his garage), about what artificial life says about the soul, why emotions are so important to intelligence and why someday we might drive cars that enjoy doing their work.

What led you to build Creatures?

I was a college dropout but I trained to be a primary school teacher. I was really lazy at it and hated standing up in front of people and speaking. But the reason I got into teaching was not really because I was interested in teaching but because I was interested in children's minds and how people grow and develop.

So you started writing computer programs?

Yes, this was the '70s when I was at college. The microcomputer had just started. I generously spent my girlfriend's life savings on a computer and taught myself to program it. I figured if I couldn't teach children to learn things then maybe I could teach computers to learn things. I thought I'd be reasonably good at that.

What are some of your criticisms of the attempts to create artificial intelligence -- you know, in the last 50 years.

Phew!

Yes, I know, there's a lot there.

It's a big subject. This all started just after the war. Everyone was used to command and control, and logistics, and very centralized views of society. People assumed that the human brain was organized on similar principles, that there was some kind of central controller inside our heads pulling the levers and making us think. The people thinking about these things were often mathematicians who believed that perfectly logical thought was the highest kind of thought. So they tried to make perfectly logical kinds of machines. But "Star Trek" has more or less demonstrated that Mr. Spock isn't always as bright as he looks. It's Captain Kirk who always comes out on top because he's got emotions and common sense and all these other things that Spock doesn't have.

People made a mistake about the machine they should be using for all this. Most people in AI came to the conclusion that the digital computer was the epitome of what the brain was like. Once they decided that, they saw their problem as: How do you make a computer intelligent? There was a kind of breakaway faction in all of this who decided that brains are not a bit like computers, we've got a hundred billion nerve cells in our brains, not one very smart machine. This half thought, "Oh well, the clever machine therefore is the neuron, the brain cell, and all we have to do is grow a few brain cells together in a bucket and that will suddenly become intelligent."

The whole AI world split in two halves. Both of them thought they knew what the magic machine was. I think both were wrong. We don't know what the magic machine is yet. I don't think we even have the faintest idea how the brain works.

It's interesting that we're basing the magic machine on something we don't understand. What is the importance of emotions in intelligence?

Emotions seem to do two things. One is that they modulate our behavior; the way we act varies according to how we feel about it. You can do the same job in many different ways: You can walk forward angrily or you can walk forward cheerfully. Mostly, [emotions are] the things that make the world mean something to us. They provide the value by which we measure things. If you don't have a means of measuring how your actions upon the world work out, and whether they're good or bad, you can never learn from them.

Emotions are what ground and connect us to the world. And yet most attempts at making artificial intelligence have assumed that the machine would just be intelligent anyway -- for example, that you might be able to make a computer that can speak English, but it won't actually have anything that it wants to say. But I think it has to want to say something. Otherwise it's just going to sit there. Emotions are what make us want and need things.

How would you build emotions in machines?

That's the tricky question.

With Creatures, you demonstrated that in some way, it is possible.

In some way. Emotions come at various levels. Something like fear is relatively easy to understand, whereas something like greed or embarrassment is a very subtle and sophisticated process. But the way things like fear, and sex drive, and maybe even loneliness get represented in the brain is perhaps fairly straightforward. The clever thing is how we recognize whether to be fearful.

In Creatures, I did it the simplest possible way. I just represented the mental state as a chemical state, which they are in us, too. Even when we fall in love there are particular chemicals associated with how much we feel like we're in love. It doesn't mean that love is nothing but a chemical, because all the complicated bits are the bits that allow us to realize that we are falling in love. But sooner or later it gets represented as a chemical. Changes in the levels of chemicals are partly what controls the way we learn and the way we measure whether what we've done is good or bad.

What ended up happening in Creatures? Did they express emotions?

It's hard to separate what they actually did from the things people imbued them with. Because it's a computer game, I deliberately made it easy for people to anthropomorphize and care about their creatures. That was the point. Sometimes people read more into it than they perhaps should. But then again that's probably true about their pet dog as well. Or maybe even their children.

But it was the emotions of people that really struck me. The first time I really noticed this was when one of my creatures fell in love with the other, or at least they became sexually attracted. There was a kind of love chase going on in the virtual world. My mother was watching this and then the program crashed. And my mom cried. I figured that I must be getting somewhere if I could make my mom cry.

So were you controlling them?

No, not at all.

You created them and then this just happened?

The important thing is that nothing inside the computer program knows what it is to be a creature. What I programmed into the computer were the rules of how to be a nerve cell and how to be a chemical reaction and how to be a gene. Then I built this huge network full of nerve cells and chemical reactions and genes, out of which the behavior of the creatures emerges. So the behavior of the creatures isn't programmed into the computer at all. That network of things can learn.

People grew to really care about these creatures, but one guy decided to torture them.

Oh, yes, Anti-norn.

What did he do exactly and what did it prove?

He set up a Web site -- it's still running, I think -- entirely devoted to torturing my poor creatures. I've never been able to make up my mind whether there's something wrong with him or whether he has a point to make. I get the feeling he does it tongue-in-cheek. The Creatures community ostracized him. He even got death threats. Somehow or other they thought my creatures were more valuable than his life.

Is this an example of how humans will relate to artificially intelligent beings and machines? As if they are real?

Yes, well, I think they are real. Just because something is manmade doesn't make it any less real. The creatures that I've made so far are not very alive and they're not very intelligent. I have reason to suppose that they're not conscious. But you can say that about a lot of natural living things. The way people react to them is quite informative. The most important thing is that it makes them ask questions. It makes them wonder about what it means to be alive, when life starts and when it stops and whether it's OK to be cruel to these things or not. If that's all I ever manage to do, then that's great as far as I'm concerned.

Why do you say they are alive?

It depends on your definition of life. I have a technical definition that is really low-level. I would say any system which manages to persist by adapting is alive. That's my working definition. These are systems -- networks -- that manage to persist by evolving and learning. But that's really a technical definition of life and it doesn't cover all the richness and excitement there is to being alive.

At one point in the book you talk about this paradigm shift about what it means to be alive. How had "life" been thrust out of its proper place?

Over the last 300 years we've come to understand machines, and it raised the question of whether we're machines. And I don't think there's any other answer but, yes, of course we're machines. What else could we be? The reason that troubles people is because they think that all machines are like the machines we've made so far. Of course, all the machines we've made so far are supposed to be unsurprising and predictable. They're really quite trivial. We get upset when we think that science says we're just like that -- unsurprising and predictable and trivial.

Somehow or another, after the last 300 years, there's come this obsession with matter. People seem to take it for granted that if anything exists it must be some kind of stuff. So if we exist, we must be some kind of stuff. That leads to a dualistic view more often than not. Ordinary stuff seems to be so trivial, and doesn't seem to be able to explain how wonderful we are, so it must be magical stuff. And that's what we humans are -- magical stuff.

When you examine that, you realize that that just can't be so. But the mistake isn't to think, "Oh well, if we're not magical stuff, we're just plain ordinary stuff." The mistake is to think that stuff is what is important. It's the arrangement of the stuff that matters. Otherwise, a painting would be no more exciting or wonderful than a lump of paper. And we just haven't gotten our heads around that yet -- the idea that it's the arrangement of things that matters.

And changing how we think about this -- what will that do?

I don't know because I've always felt this way. It's taken me the last 20 years to realize that this is the problem. It's something to do with richness. The number of kinds of stuff in the universe is really small. There's only 92, or whatever, different kinds of atoms in the universe. When you start thinking about everything being kinds of stuff then the world becomes rather pale and limited. But when you realize how many different ways you can put that stuff together ... take sculpture for example. Clay is made of two kinds of stuff -- silicon minerals and water -- and yet there's an infinite number of ways you can put them together to make an infinite number of sculptures. Once you start to think about these relationships being the important thing, you suddenly realize that the universe can be much richer and much more deeply interconnected than it was before.

What about the doomsayers? What are so many people afraid of when it comes to intelligent machines?

It's a very odd attitude, don't you think?

It is once you've explained that machines aren't very smart, they don't have emotions, they're not intelligent, so where would they get the motivation to take over the world?

Computers don't have that motivation; computers aren't intelligent. We'll only get intelligent machines when they do have emotions. When we do, when that happens, they're not going to be much different from all the other machines we know that have emotions like lions and tigers and people.

If somebody went out to Borneo and discovered a new species of monkey tomorrow, the papers wouldn't be full of "Oh my god, are the monkeys going to take over the world?" It never occurs to us that natural species might take over the world -- we're more than happy to share the planet with 10 million kinds of natural species. I can't see a distinction between that and artificial species. When you think about it, where did the idea come from in the first place? Science fiction writers. Their job is not to say how the world is going to be. Their job is to make a good story. A story entitled "Invasion of the Terribly Nice Intellectual Robot" wouldn't sell very well, would it?

Some people thought Y2K was an early example of this.

Yes, and that's an example of how stupid machines can be. Give me an intelligent one any day. I like intelligent machines.

So what would an intelligent car be like, for example?

Well, there may never be such a thing. But we used to have intelligent cars; they were called horses. And they used to know stuff that our cars don't know. They used to know where they lived and how to get home and how not to knock over people. Even how to refuel themselves. The amazing thing was that they could even make new cars. The intelligent car would be like a horse. Something that really enjoyed a good drive and prided itself on not knocking people down.

You think it's possible for machines to enjoy their work?

Yes, one of the reasons people worry about machines wanting to take over the world is because human beings want to take over the world. We're a miserable lot. A large part of the reason we're miserable is that most of us are being oppressed in one way or another and being forced to do things we hate. We all want to be someone else -- like the king or a film star or anybody we envy. Most human strife comes from envy. There's no reason at all, if we made machines do those things we hate, why those machines should hate doing them. It would be stupid for us to design machines that hate doing the jobs they do. If they enjoy doing them, why would they envy anyone else?

If they had the ability to enjoy doing their work, would they then have the ability to decide that they didn't like it anymore?

I think they have to have that. If you want to make something really intelligent, then it has to be free, but no freer than we are. We're pretty trapped in the world we're in and they would be trapped in the world they're in.

What incentive would they have, though, to do this work?

Because they'd enjoy it. We evolved to live in the jungle. All our emotions are tuned to certain kinds of relationships. Certain things excite us and certain things we find unpleasant. But now we don't live in the jungle, we live in the concrete. That's why there's so much angst in the world. If you're going to build intelligent machines to do specific jobs, then you're going to tune their emotions to the environment you want them to live in. They'll be happy there.

Do you think that human beings will feel differently toward machines if they are aware that these machines have feelings?

Ethically and morally we'd have to give them the same rights that we give other living things. But at the moment we don't know what those rights ought to be. We don't know what those rights ought to be for cows and children. The human race breeds cows and then shoots them and eats them. It's a pretty strange kind of thing to do when you think about it. Sooner or later we have to figure these things out and what rights living things have. We're going to have to figure it out anyway, intelligent machines or not, because we have to worry about cloning, genetic manipulation ...

And abortion.

Yes, I think we've been too glib about it up until now. It's been easy. A hundred years ago people were either dead or alive, and you were either born or you weren't and that was all there was to it. That's not true anymore. You can be kept alive, whatever that means. You can be cloned.

How will artificial life help us figure this stuff out?

It will give us more examples of life. We're judging all these issues on a sample of one: the kind that evolved here on this planet. If we invent machines of our own that are alive or if we suddenly got invaded by aliens, then that sample would jump up to two and we'd have a wider understanding of what it meant to be alive.

Are you still working on Lucy?

Yes, I hope I always will be.

What are you building exactly?

I don't mind standing up and suggesting that the creatures I made before are alive, but they're certainly not conscious. I started asking myself why. The first thing that struck me that was missing was that they have no imagination. They're just automated. They react to their environment, they can't think ahead, they have no sense of the future, they can't build models in their head and they can't worry about what you think because they can't imagine what it would like to be you. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that everything that we care about in what it means to be human has something to do with imagination. I set out to try to figure out where that comes from.

She is an orangutan?

Ostensibly. She's a heap of aluminum with something vaguely like an orangutan's head.

What is her brain?

She doesn't really have one yet because I'm still working on the theory, but it will be made out of simulated nerve cells and chemicals, just the same as the Creatures' brains but very much more complex.

What are you hoping for with her?

I'm not exactly aiming high. One thing that is really important for intelligence is learning. If a system doesn't learn, it can't be considered intelligent because its behavior has been programmed into it. When you think about it, most people think that artificial intelligence just kind of arrives fully formed. But even Einstein took five years to tie his shoelaces. If we're going to make truly intelligent machines, they have to start as babies, knowing nothing and learning where their body starts and ends and who Mommy is and what being a naughty girl is about. All those things that children learn in their first year that we pay almost no attention to. I'm aiming to get something like a 4-month-old baby, which doesn't sound very impressive but it's amazing what a 4-month-old baby knows.

How long have you been working on her?

Two years.

Is anyone else working on similar projects?

Vaguely similar, yes. There are plenty of people building robots, but I'm not aware of anyone trying to do it the way I'm doing it. The theories I'm trying to test out are new. This approach to robotics is certainly unusual. But there are tens of thousands of people interested in how the brain works and how to make machines more like it.

Can you conceive of any way that this could go wrong? The whole "if an amiable, intelligent machine fell into the hands of an evil person" idea? In the book, you mention how we might use this for military purposes.

Bad people can do bad things with anything. That's not a reason to stop doing it. There are military applications for spoons. We'll have to worry ourselves about the ethics of making spoons. It's a separate issue whether they should be used by the military. A few months ago I was on the radio, on the BBC, talking about this subject with somebody who was arguing that we shouldn't do AI because it has military applications. He said, "One day there will be intelligent military machines." And I said, "We already have intelligent military machines. They're called pilots." I regretted saying that because that day happened to be Sept. 11. But it is true: we already have intelligent machines and they're people. If we make intelligent machines in the future, they'll only be variations on that. Another life form. We already share the planet with 10 million other life forms and don't think twice about it. People might argue that these life forms will have super-titanium bodies and turn into these huge and unstoppable machines. But that's going to be true for human beings as well. The more time goes on, the more like machines we get and the more integrated with technology we become.

Are you saying that intelligent machines would be indistinguishable from human beings?

Indistinguishable from other living things, yes. No different from us than a leopard or an elephant is different from us. If you look at the variety of living things on the planet right now -- a cherry tree or a mushroom or bacterium -- there's this huge repertoire of living things. Large numbers of those things we've managed to kill off. Maybe one day we'll create a few replacements.

You're an atheist, but you claim that you're on a spiritual journey. What does this all say about the soul?

I don't know the answer to that yet. Again, it's the problem of thinking of the soul as some kind of stuff. The way we view the world is wrong. We haven't seen the right way of looking at the universe yet and when we do, then some of these spiritual things will start to make more sense.

You say that someone passes away and you call up their memory in your brain -- you simulate them -- is that in some way their soul?

I don't know. There could be some truth in it. If that is their soul, then there's not one soul per person. You might have many people who think you up. You're in many places at once. That's one thing we've learned about organization and information -- you can copy it. We like to think that we're one person when we're alive, but even that's not true. Our brains are made out of 100 billion working parts, none of which are in charge, none of which understand the existence of the other 100 billion parts. You can do bizarre things like cut someone's brain in half -- people who have severe epilepsy have the corpus callosum cut in between the two halves. In a way, they turn into two people then, each having control of half a body, often with different tastes in clothes.

Is the idea of the soul what's interested you from the beginning?

The way I look at it -- and I borrow this idea from Richard Dawkins -- the universe has been around for 15 billion years, during which time I haven't existed. According to astrophysicists we have another 15 billion years to go, during almost all of which time, I won't exist. Then there's this tiny flicker in the middle when I find myself here. I want to know what that means. Where did I come from? Where am I going? What am I doing here? And quickly, I haven't got long.

Shares