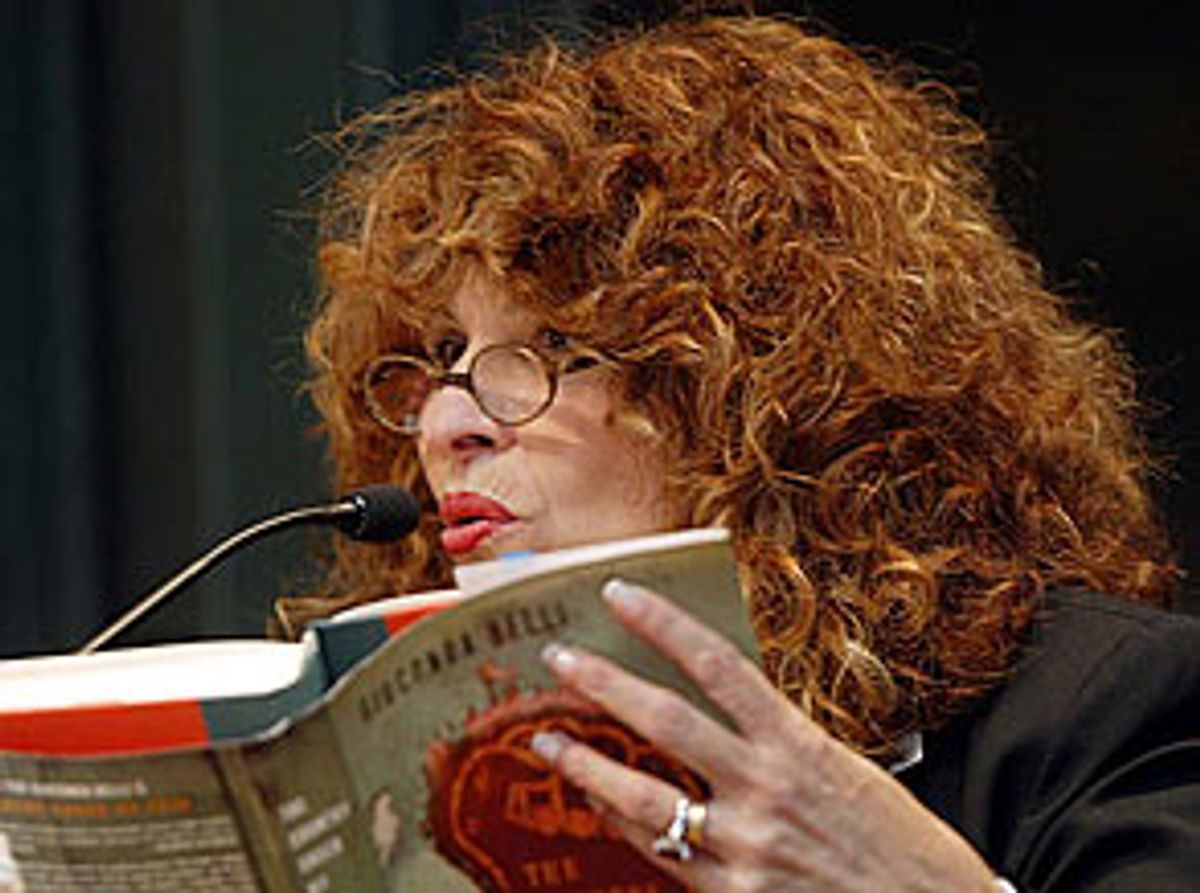

"I had exposed myself to bullets, death; I had smuggled weapons, given speeches, received awards, had children -- so many things, but a life without men, without love, was alien to me, I felt I had no existence unless a man's voice said my name and a man's love rendered my life worthwhile," writes Gioconda Belli in her memoir, "The Country Under My Skin." Clearly, Belli, a Nicaraguan Sandinista and award-winning, groundbreaking poet, is no wimp. At this point in the book, Belli has suffered terribly over an emotionally tormented love affair with a Sandinista guerilla named Modesto, whom she was working with at the Nicaraguan ministry of planning, and swears to change her ways. Still, how did a brave, brilliant rebel become submissive to and obsessed with her compao?=ero?

In "The Country Under My Skin," Belli unravels these contradictions -- as she says, all too common among powerful women -- with characteristic candor and dignity. Her often joyous, surprisingly fluid memoir phases in and out of Belli's romantic and political life, the tumult of her love affairs sometimes coinciding with moments of upheaval in her homeland. Belli, a member of the upper class, joined the growing Sandinista movement in 1970 when she was just 20 years old, and four years later fled her stifling and unhappy six-year marriage. After the rebels ousted Nicaragua's reigning Somoza regime in 1979, Belli went on to hold intermediary positions in the Sandinista government. At the height of the U.S.-funded Contra war in the early 1980s, Belli, then working in the media department at the Sandinista party headquarters, fell in love with Charlie Castaldi, an American reporter. Eventually, Belli and Castaldi married and moved to the United States, where Belli still lives six months of the year. She spends the other half of her life in Nicaragua. The author of "The Inhabited Woman" and other works of poetry and fiction, Belli spoke to Salon from Los Angeles.

You write about your intimate life and your life as a Sandinista. Why did you want your book to be a memoir of love and war?

The important thing about the memoir was to show how social upheaval also has an impact in the personal life. From the perspective of a woman, intimacy is not separate from the political. I thought it would be interesting to do a parallel between my own process of liberation and the liberation of the country. The rebellion was expressed in a revelation.

A Nicaraguan poet wrote the introduction to my poetry and he said, "A woman who reveals herself is a rebel." There is a streak of rebellion in me in that regard. I've also liked to defy these notions that women are spiritual beings. We are subjects of our own sexuality. We link our intimacies with whatever public role we play and give it the same level of importance, which is hard. Sexuality surrounds us like a dangerous aura. The same reverence that is given to the spirit is not given to the flesh. We have had a sexual revolution, but the sexual revolution only has made sex more pervasive. It hasn't granted the level of reverence and respect that it should have. We are so determined by our sexuality and our biology; we end up being this dangerous creature.

The privileged society from which you came did not approve of your poetry. But what I thought was interesting was how your mother took you aside when you got married and said you can and should do whatever you want for a man sexually.

I had a very good sexual education. My mother was very advanced in that regard. She conveyed to me the sense of reverence and wonder about my body and the powers of my sexuality not only to give life, but also to be a whole person and to enjoy pleasure. It was put to me as an almost holy act.

You got married when you were 18; your parents discouraged you from going to medical school. Had you already been awakened to what was going on in your country?

Yes, I grew up in a very difficult country, a very oppressive situation because of the Somoza dictatorship. My family was in opposition to Somoza; Somoza was a liberal and my family were conservatives. These were the two traditional parties in Nicaragua. Members of my family had participated in plots against Somoza, and in rallies against him. When I was young, I would see pictures in the paper of mothers holding their sons that had been killed by the National Guard. A student was killed near my house and that splash of blood was etched in my mind. But it was a constant sense of being defenseless -- a hopelessness that there was no civic alternative.

Even for the upper class?

Even for the upper class. Somoza allowed them to prosper economically until the 1972 earthquake. The earthquake altered that kind of equilibrium between the upper classes and Somoza. When that equilibrium was altered, the upper classes began to defy Somoza and to criticize him more openly. Also, the most important newspaper in Nicaragua, La Prensa, had a very critical stance against Somoza. The director was killed by Somoza, by the paid assassins. That was one of the sparks that began the insurrection in 1978.

How did ordinary Nicaraguans feel about the Sandinistas? How were they regarded?

In the beginning, it was a clandestine organization that sponsored armed struggle. So we admired them secretly because they were very brave. They would face off with the National Guard in very lopsided encounters. But we were afraid of them. We felt that it was a radical position. Then everything began to change when things got so bad with Somoza -- when the earthquake happened and all the international aid was stolen by his dictatorship. People were outraged. It got to the point where it felt like [we were acting out of] self-defense: A burglar comes into your house to rape you and take everything and you have to resort to self-defense. That was the point where things began to change and everybody began to support the Sandinistas in 1977.

Before that it was very risky to join the Sandinistas. But more people -- especially young people like me -- started to get involved.

What kind of people typically joined?

They were from all walks of life, really. The Nicaraguan struggle was not a class struggle. It was more like a struggle where people from all social classes participated because it was a struggle against tyranny that affected everybody. The participation from the upper classes began to be in bigger numbers later on. When I joined there were not many people from the upper class.

You were working at an ad agency and you say that ad agencies were refuges for bohemians, poets, revolutionaries. How old were you when you first met the man you call "the Poet," the one who eventually introduced you to Sandinistas?

I was 20.

Were you absolutely sure that you wanted to join? How strong were your political beliefs? Were you mostly swept up in these heroic people that you met?

People might think that I was a "vaginal recruit." A horrible term. I refuse to accept that. The fact that I talk about it in my book doesn't mean that my political stance was determined by the Poet, or by the people that I knew. I had it in me because I had lived through what I had lived. I was young but, at the time, I was already feeling that it wasn't right, that I wasn't just going to be a married woman and forget about the rest of the world around me and live in this bubble where the upper class lived. I already had my own thoughts and ideas. I had read a lot in my life.

I had met another man who was involved with the Sandinistas. The Poet didn't really recruit me; the man who recruited me was Camilo Ortega. But the feeling that I could transform my life and empower myself as a citizen and as a person was what allowed me to break from my marriage. A marriage where I was quite unhappy. It was a combination of things that led me to defy convention and have this affair with the Poet.

It was also the time of the sexual liberation. People were talking about open marriages. It was all those things combined. But never was my political stance determined by the men I was with. I had my own ideas. I liked the Poet because he opened doors for me not only in terms of getting to know the Nicaraguan history better but also everything that was going on in literature in Latin America.

It seems as if it was a very happy time in your life as well, a very joyous time. We all have these idealized images of bohemian life and it seems as if it really was wonderful. Was it?

Yes. It was joyful. I had spent years with a very sad man and [lived in] this very constrained and rigid society where I was not to have any kind of freedom except for what was set for me. And then I was a participant in a historic endeavor and of course it gave me a sense of purpose and meaning. It introduced me to a group of people who wanted to change the world, who were intellectually stimulating, who were very inspired by idealism. I was elated.

You had a daughter at the time and eventually four children. How did you reconcile that? You must have been torn.

I wasn't more torn than a lot of people who work. It's a woman's curse because children are still considered the responsibility of women, when they are not. They are the responsibility of society. They are the future men and women of the world. Women carry the burden of responsibility and we carry it very much alone. It's very unfair. So we are made to feel guilty about choosing any other avenues of self-fulfillment. It's a social trap, and a woman needs to think about the world her children are going to grow up in.

I was torn because I had all these traditional beliefs inside of me but alongside the traditional beliefs, I also had the other part of me that told me, "No, this is not right. I have to care about the world my children are going to live in."

And that was the attitude of most Sandinistas?

I had a conversation with Camilo and I said, "I have a daughter, I am afraid." He said, "Well you have to do it for your daughter because if you don't do it, your daughter is going to have to do it. If your parents had done it, you wouldn't have to be doing it." It's true. That settled the question for me.

I am convinced that the reason why my kids have become very fulfilled and achieving human beings is because I wasn't raising them alone. In the process of raising them, all those years of exile and everything, I had a lot of people around me that were good role models for them. They saw all these people who were nice to them. We had all these people who would stay in our house who also took care of them.

What exactly were you doing for the Sandinistas?

One of the things was driving clandestine operatives to Managua; they wouldn't drive, you had to bring them. I was a courier because at that time there was no fax, no e-mail, nothing. All the telephones were tapped. They would communicate through letters and the letters had to be delivered. I had access, because of the work I did, to information about the corruption of the dictatorship -- I handled a few accounts that had to do with businesses where Somoza was involved. I would extract documents.

I was involved in an operation in 1974 and I was able to go into different embassies and draw blueprints. For the people who were running things in the mountains, we had to get medicines and supplies, we had to prepare safe houses. I participated in a cultural group and we would go to the different barrios and have organized happenings where we would do public poetry readings and we would rally people and give them a consciousness-raising session. We would do it very quickly because the National Guard would come and we would have to run.

What did the National Guard and the Somoza government do in response as the Sandinista movement gained momentum?

They began the big wave of repression. For example, after 1974, when the Sandinistas did an operation in December, they began taking hundreds of people to jail and torturing them. They established a military tribunal to try and condemn all these people who were accused of being Sandinistas. I was tried by one of these tribunals. You didn't have any defense. [Belli went into exile.] They would keep people in solitary confinement. The people who were caught were tortured horribly. In the book, I tell the story of the man who was buried up to his head and left there for a week. Women were raped systematically, electric shock was applied, they kept them handcuffed to walls. It was a horrific dictatorship. They would take people in the countryside who were accused of collaborating with the Sandinistas on helicopter rides [and throw them] from helicopters.

How did you feel about the possibility of killing someone? You write about being chased in your car and gripping your gun.

It was self-defense. That's how I dealt with it. The National Guard had a model -- they didn't want to catch Sandinistas, they wanted to kill them. We knew that. The thing was to defend ourselves. If we were going to go, we were going to go causing a lot of casualties. That was the way the struggle was. But it was hard to deal with those things.

Also, we hated those guys, those soldiers. They were really brutal. In Nicaragua, the soldiers would control the streets dressed in combat helmets, even the police had combat helmets. They were killers.

How were women in the Sandinista movement treated?

During the struggle against Somoza, I felt that I was treated as an equal. My disillusionment came afterward not so much because of the way I was treated but because we had big aspirations for women. We wanted the situation for women to change more radically. But the situation for women in Nicaragua advanced because we were in important intermediate positions. We were able to fight the resistance with men. In Nicaragua now, we have had more women in high positions of power than any other country in Central American. Of course, we were fighting for total equality. At moments I would feel it was unfair that women would not be able to participate at the highest level of government.

It seems that at times you had two personas. You were a different person when you were with one of your lovers, Modesto. Did your personal life ever affect your political life?

My episode with Modesto was a demonstration of the contradictions that we women live with. On one hand, I was a woman who wanted to be very liberated and very self-affirming and sure of myself and struggle for women's rights. On the other hand, I fell in love with this guy. And I became this goo. It was a terrible moment in my life. I realized, my God, I was being stupid. And I was able to break that submissive relationship I developed with this guy. But it happens a lot. It happens to the most brilliant women. One of the reasons that I wanted to write about it was because I thought it was important to talk about it. It's this contradiction that we have. Our emotions, because we give them a lot of importance, sometimes override our reason.

You also write about your experiences meeting such powerful leaders as Fidel Castro.

I would find myself in situations where I would be feeling that these were compañeros, comrades who were supposed to treat me like a political person, somebody who was doing her job in a political movement. Then this other part of the equation would interfere and there would be sexual tension.

I thought these episodes were pretty fascinating -- how men react to power and what power makes them believe they can do. I cannot say that Fidel Castro put the moves on me. But it was a very strange situation; he was obviously flirting with me.

Didn't he say something like, "Where have they been hiding you?"

Yes, obviously something fishy was going on.

Some of the other Sandinistas did not react well when you started to date an American.

Yes, when I began to go out with Charlie the concern that was expressed to me was that he was an American journalist [for NPR] and we were at war with the United States and that was not the right thing to do because I knew a lot of secrets. At the time I was the executive secretary for the electoral commission. I had a lot of information. But I realized that other men did these kinds of things -- men who worked in the secret service of Nicaragua, who were dealing with information much more delicate than what I handled -- would go out with American journalists. Men were not supposed to lose their heads when they dropped their pants. But [women] were.

And so what did you do? Threaten to leave?

Yes, I said, "If you don't trust that I can keep my head then you better fire me." But they didn't fire me. Charlie got in trouble too, you know. [State Department official] Otto Reich sat him down at an editorial board meeting at NPR and accused him, saying that the Sandinistas were providing women for him and were paying him to spread Sandinista propaganda. They spread a whole campaign of rumors against Charlie and other journalists.

This has been in the news recently because of Otto Reich being assigned undersecretary of state for Latin America. They did worse things to Charlie than my people did to me in Nicaragua.

Do you blame the United States or the Ortega brothers for the eventual failure of the Sandinista movement?

I think there was responsibility on both sides. I do attribute more blame to the United States because it's a bigger country and it should have known better. Also it's a pattern that the United States has had in Latin America, a very misguided foreign policy that has caused a lot of pain and suffering to the people in Latin America. Every single project of social reform in Latin America has been attacked by the United States. Nicaragua is not the first case; it happened in Guatemala in 1954, in the Dominican Republic, with Allende in Chile, in Peru. Nicaragua was caught in this East-West confrontation. Nicaragua was a very tiny country trying to do social reform and trying to change things for the majority of the people. The United States went with all its might against this country and used very dirty and unlawful tactics -- covert war, setting fire to all of our oil reserves, putting out a CIA manual on how to kill Sandinistas, declaring Nicaragua a threat to the national security of the United States.

The United States claimed to believe that Nicaragua was this dangerous communist country. How would you characterize the political aspirations of the Sandinistas?

We wanted to do a very radical reform in Nicaragua, but we were not communists. I will say this until the last day of my life. We did not approve of the restrictions on individual freedom that were placed in other socialist bloc countries. We wanted to have freedom of the press, freedom of travel and religion. And we did. We had elections and turned power over to an opposing force in 1990. It was the first time ever in history in Nicaragua that a party had given power peacefully to another.

Obviously you did not support the new party, or that new president, Violeta Chamorro.

No. I'll just give you one figure. In 1990, in a list of 135 countries put out by the United Nations -- quality of life indicators -- Nicaragua was No. 85. Now, it's No. 127.

We have made a lot of democratic gains. In a way Sandinismo was the facilitator of democracy in Nicaragua. The Sandinistas have been the second largest political party. Sandinismo left an army that's not oppressive, that's professional and organized, and a sense of empowerment for the people. That for me is the legacy of Sandinismo.

But these governments that have come after have not cared about the situation of the people. The mortality rate for women is the second highest in Latin America. Nicaragua after 1980 was the poorest country in Latin America. Seventy percent of the people lived with less than a dollar a day.

But we were not communists. We did affect certain rich people because when you are going to redistribute wealth in a country, you have to ... and those were the people who began to accuse us of being communists.

And the Ortegas?

We began to have the Contra war, and in the situation of war -- you have begun to see that a little bit in the United States after Sept. 11 -- democracy and wars don't go together. When you get attacked, people who have authoritarian tendencies have a field day because you can justify every authoritarian behavior by saying that you are protecting the security of the people. The United States in a way facilitated authoritarian tendencies to emerge. We didn't have any democratic training. We had been in a dictatorship for 45 years. The United States was asking us to be more democratic than they are here.

Then what is it like for you now living in Los Angeles? Were people angry at you for moving to the United States?

I felt bad, but at the same time I felt I wanted to understand the United States better. Since 1986 I decided that I was a better writer than politician and that I should concentrate on my writing. It was a hard decision but it was part of the compromise of my relationship [with Charlie]. And I thought that the United States wasn't only the country that attacked Nicaragua but also the country that had produced Mark Twain and William Faulkner and Eudora Welty. I didn't have this feeling that the United States was a one-sided empire. And, of course, we all have to reckon with the United States.

And I live half of my life in Nicaragua. The way I have been able to reconcile my life here has been by keeping very close proximity with Nicaragua. That's why I call the book "The Country Under My Skin." I take it with me, I have it with me, I'm always current about what's going on. I write Op-Ed pieces all the time. I am an active participant in the political life of Nicaragua.

And your children?

My son lives in Nicaragua. My daughters live in the United States.

Do feel that you have created a better Nicaragua for them?

Yes. Just the fact that there's no repressive army, there's freedom, there's democratic possibilities. It's a different country. It's been a very interesting experience in terms of the growth of the country -- to grow into a democracy is very hard. We still have a lot of politicians who are trying to interfere in the process and manipulate it. But they're creating institutions to combat that.

What I have realized is that in history we are like a blip in time. To think that I would have seen all of my dreams come true would have been delusional. We have to do our share and hope that people will do their share when their time comes and to advance the wheel of history a little bit. It's our responsibility. I feel I played my part the best that I could. And I still have a part to play through the books that I write.

Shares