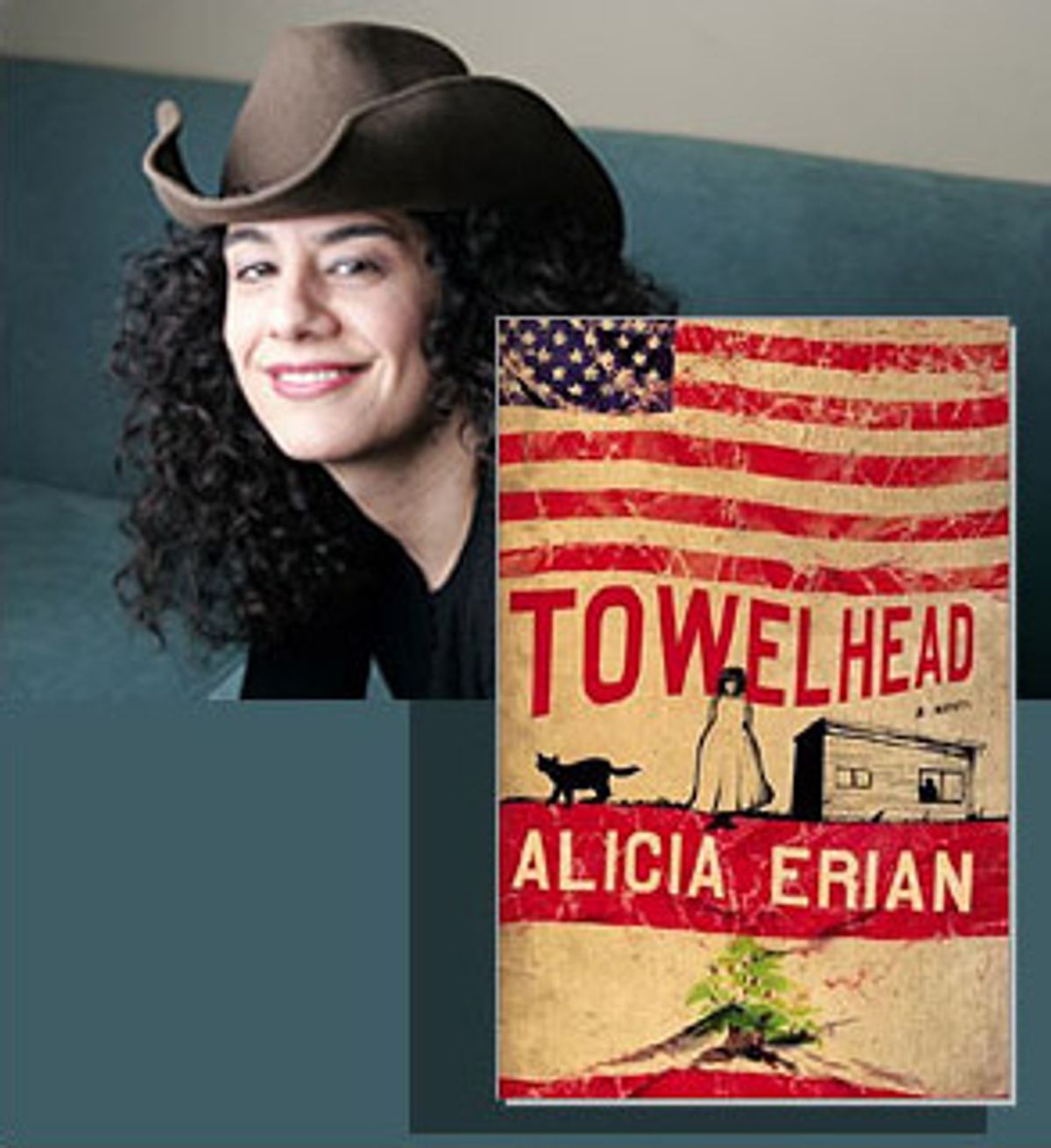

"My issue with fiction is there's too many damn dull moments," Alicia Erian says with characteristic candor. That's one charge you can't level at "Towelhead," Erian's provocative, taboo-defying first novel and the follow-up to her acclaimed 2001 short story collection, "The Brutal Language of Love." "Towelhead" is narrated by Jasira, a 13-year-old girl sent to Houston to live with her Lebanese father after her American mother's boyfriend takes an unsavory interest in her. A harrowing, frequently hilarious coming-of-age story, the book's depiction of abuse, racism and sexual desire resonates with frightening plausibility.

Set during the first Gulf War, "Towelhead" follows Jasira as she tries to process the ever-changing rules of her often abusive father -- whom she calls "Daddy" -- while struggling with her feelings for Mr. Vuoso, the mercurial, muscle-bound Army reservist who lives next door. Alternately cruel and crudely loving toward Jasira, Mr. Vuoso also owns an impressive stash of Playboy magazines that Jasira savors whenever she baby-sits the Vuosos' bratty son, who calls her the slur that gives the book its title. Much of the novel's suspense comes from Jasira's breathtaking tendency to make one bad decision after another, based almost solely on her need for the sexual pleasure that stands in for the love and attention lacking elsewhere in her life.

"Towelhead" is a compulsively enjoyable and thoroughly uncomfortable book to read. Its unapologetically graphic portrayal of teen sexuality and the ambiguities of physical and sexual abuse are almost certain to provoke shock and controversy. Erian, however, seems ready to handle whatever reactions her subject matter inspires, and speaks with the frankness that's at the heart of "Towelhead." The daughter of an Egyptian father and American mother, she also possesses a few striking similarities to her narrator. From Wellesley College, where she teaches writing, Erian spoke with Salon about those similarities, as well as the intricacies of racial slurs, the importance of Mary Gaitskill, and the pleasures and pitfalls of having a 13-year-old narrate your first novel.

Reading the book, the first thing that struck me was Jasira's voice -- it's so simple and naive, but consistently compelling. How did you find it?

It took a while. The first draft I wrote was 100 pages and we sold the book based on those. But then I ended up throwing them away. Part of the reason was that her voice sounded too old, and a little too detached and formal. I don't know why I was doing that. I know in part: I'd never written a novel before and I had this idea that it should sound like, hoity-toity. [Laughs]

Serious and authoritative.

Yeah! I thought, OK, enough with these silly short stories, now I have to sound fancy. Part of it was just some stupid idea I had about novels. So it was a hard voice to maintain because it wasn't an honest voice. It was exhausting. And my editor said, "You've got to work on that voice because it's a little off -- she sounds too old." So I sort of toned it down and tried to make her sound like a kid.

Was maintaining her voice a large part of the challenge of writing the novel?

It's really hard to stay in the moment of the novel. Short stories, I've learned, are kind of cheating: You're in and out, and have no obligation. With a novel, it's like every day with these people. Initially, I was going to jump ahead in time and my editor said, "Look, I'm already doing another book that jumps ahead in time, and I don't feel like doing two." That was her reasoning. But it made sense, because I thought, it's cheating. I shouldn't say that, because now everyone who has a book that jumps ahead in time will be like, Fuck her!

What made you decide to write a novel, anyway?

My agent told me to. [Laughs]

Are you serious?

Yeah, he was like, look, if you want to have any kind of career, forget about these stories. Stop messing around. I said OK. I didn't want to, but I knew he was probably right.

How long did it take you to write the book?

Three years. Which is probably not that big a deal. But it felt awful. Every minute of it. It was depressing; bad things were always happening to [Jasira]. I'm not an actor, but I have to imagine they have similar lives, having to take on people's personas. I used to work eight hours a day, but at the end, I just couldn't tolerate it for more than two. And I also worried -- it's a lot to keep track of. I can be slightly feeble. [Laughs] There aren't even that many people in the book, but everyone has to be given appropriate screen time.

Well, honestly, right until the end, I was wondering how it was going to get wrapped up.

You and me both! I had no plan. The plan was to be honest. I believe that if you tell the truth and stay in the moment with the characters, then you get the prize. The prize is that it will come together, there will be some way to make it make sense. I was banking on that, because if I know what's going to happen, I won't write it. I'll be instantly bored.

Where did you get the idea for the book, and where did Jasira come from?

Did you ever watch old "Saturday Night Live" tapes of when Gilda Radner was on?

Sure.

Ok, remember the character she used to do, this little girl in a nightgown named Christine? Her parents were always yelling, "Christine, don't touch that! Christine, get over here!" And she was always running around like a robot. It was to me the most horrifying and yet funny character; I always felt like that as a kid. Part of Jasira is modeled on [her]. And the book in general -- when I was a little bit younger than Jasira, my mother sent my brother and me to live with my father, who is Egyptian, in Houston. It was sort of a nightmare. After about seven months she came and took us back. I never wanted to write a novel, and the only idea I ever had if I was going to write one was, "Gee, I wonder what would have happened if she hadn't come and taken us back?"

So the idea for the novel is basically this what-if premise. And I had also separately baby-sat this boy whose father, an Army reservist, had a giant collection of Playboys. The last piece was the Gulf War. The hundred pages had a lot of the stuff with Daddy, Mr. Vuoso and Zack [Mr. Vuoso's son], but it wasn't working. Then September 11 happened and I went out to lunch with my agent and I was saying, I'm writing this book about Arabs, is it going to be a problem? And he was like, no, it's not going to be a problem because it's not a political book. And then it hit me, like, wow, it really should be a political book! [Laughs] If that's going to be a problem, we should make it a problem. I thought that the last thing that the book needed was this setting: Everybody could get really tense, and it would be this scenario that characters could bounce off of. It was like another character. They all needed that war to talk about and get upset about.

And you can use the first Gulf War to comment on today's politics.

That's right.

Especially the anti-Middle Eastern sentiment. Had you chosen the war, then, for that reason?

Sure. It was a really nice way to be able to do that, and often I felt that I was doing exactly that. But the other nice thing about having [Jasira] narrate the book was that it limited the flow of information -- you have a kid talking. I did that on purpose. I wanted to be responsible for as little information as possible! [Laughs]

Remove the culpability.

Right. That's all she knows; she's only 13. And then she would get Daddy's politics, and Mr. Vuoso's politics, and all the adults' politics filtered through her kid's brain. In some ways I felt like I copped out, that I could have made it more political. But you're careful about these things, because you want people to read your book.

Daddy's such a nightmarish character -- I can see some people reading the book and thinking he conforms to the stereotype of the oppressive Arab man, beating his daughter. When you were writing him, did you worry about that?

I did think about it. But I would say that -- let me choose my words carefully -- well, the first thing that interests me about that character is that most people who read the book -- strangely, mostly men -- the first thing they say is that they really like Daddy.

That wasn't my experience.

Yeah, I know. They think it's bad, how he beats her, but the person they hate is the mother. But I think it's mostly men that feel this way. They say that Daddy's bad but in his own way he wants what's best for his daughter. I did worry that he was playing into a stereotype. At the same time there is certainly some truth to the story. It's somewhat autobiographical and I have every right to write my life.

How much of "Towelhead" is autobiographical?

[Pause] I mean, I can't answer that question.

I figured it was very personal, but from what I knew of your own background, I felt like there had to be some element.

Right. There's definitely some element and then a lot of it's made up. I'm still trying to come up with a really good answer to that question, because it's a question that I would like to answer. But at the same time, I don't think it's a question that I can answer in an interesting way. I mean, if I had written something that was nonfiction, then we could talk about it in an interesting way. I also have concerns that it ruins what the book is. Part of fiction is reading something and thinking, Is that really true? Somebody said they read the book and thought, Is there really a girl out there who's like this, and did this or felt this way? Part of what's thrilling about fiction is being left with those questions and not necessarily having the answers. Writers will, I think, fairly often feel like they can ask each other, "Is that true?" If it's not true, then I can think, your level of craft is astonishing. And I can also feel very disappointed that it wasn't true, even if it was something horrible. So I just hate to mess with the fictional integrity of the book. But I am happy to say that it was a what-if story, that we did go and live with my father, that he certainly had the capacity to be abusive, and that there are certainly plenty of true things in the book, but there are plenty of things that aren't true. Although I will say that for me, the book emotionally is entirely true. Every emotion in that book is something that I definitely know.

I feel like anyone who was a 13-year-old girl at some point can relate on some level to what Jasira goes through. The decisions she makes based almost solely on what she's feeling certainly felt universal. In some ways, "Towelhead" reads like a radically updated version of "Are You There, God? It's Me, Margaret."

[Laughs] Times 50.

Were you influenced by young adult books?

I was a huge reader of young adult novels as a kid. When I became too old to read them, I was devastated. I had a terrible time transitioning from Y.A. books to adult books. My mother's a librarian and she'd try to bridge the gap. But I missed reading about those kids. I read a lot of Judy Blume, Lois Lowry, S.E. Hinton and Robert Cormier. It's a great genre. I haven't followed it since [then], but certainly when I was a kid, I loved that stuff.

When you were creating Jasira, did you grapple with how to handle her relationship with sex in a way that wouldn't be construed as sensational or make people think of, say, Larry Clark?

[Laughs] Larry! I think about him all the time. But that was the other reason to do the kid voice: She would get to talk about her sexuality. If someone else like Mr. Vuoso had talked about it, it would just be a book about a pervert or something. Jasira's relationship to her sexual life is very complicated. She falls into this life accidentally because she has these parents who are not very good parents; they're somewhat inattentive and selfish. She feels neglected. And then the mother's boyfriend likes [Jasira], and she discovers that there's a way to be liked. When she moves in with her father, it's a nightmare. He's frightening and she can't figure out what his rules are because they change all the time, and he's violent. Then she gets into this thing again where this guy pays attention to her. I think when you're that young and lonely, and you're feeling that beaten by the people you're not supposed to feel beaten by, you really don't have a lot of control about where you're going to get your attention. Her relationship to sex becomes sacred to her: It's the one part of her life that feels good. I don't think Jasira has any agenda, except to feel good. Her goal is not to titillate the reader. It's my goal, because I have a view about abuse, that it is titillating, and that we're never allowed to say that it is, but in fact when we read about it, it's titillating.

Why?

Because sex in general is titillating and everyone has their own pathology, which means they're going to pick one side of somebody dominating or being dominated, and there's a lot in there that's going to set them off or make them horny. That's a fact. But if you say that, that's bad. Mary Gaitskill, who I didn't mention before, is the most influential fiction writer in my life. Particularly her story "Secretary," and not the awful film that was made of it.

You didn't like it?

No. It's horrifying to me. The story is about a very depressed girl with a horrible home life; it's relentlessly sad and bizarrely funny. Its genius is that she's in an awful situation with a bad guy and it's not pretty and funny like the movie, it's awful. And instead of thinking, "Get out of there, girl!" the reader's going, "No, just please stay, just let him do this." And I read the story and thought, what the fuck is wrong with me? Because this writer has made me want a horrible thing to happen to this girl, and I'm really horny. And then I thought, that's what a real writer does -- a real writer makes me feel like I read this wrong. She made me feel like a messy human being. And I never stopped thinking that the goal of writing is to make people feel like messy human beings. When we feel messy, we're more at ease with ourselves. The point is that the book should titillate because there's nothing illegal about being titillated by an inappropriate scenario. It doesn't mean that I want some kid to get abused or I'm going to abuse some kid. But the point is, that's not Jasira's goal. She's just telling the story. My goal as the writer is to do what Mary Gaitskill did to me. Because I felt like that was a very complicated and rich reaction I had. That story changed my life.

Speaking of complicated reactions, did you choose the book's title?

I did choose it. Under duress. [Laughs]

How did that happen?

Originally, it was called "Welcome to the Moral Universe." Daddy has a speech where he tells Jasira something about the moral universe, and I liked the speech. Probably, I also really loved the movie "Welcome to the Dollhouse." [Laughs] My editor, who's a very sharp woman, didn't say anything until I completed the manuscript, and then she was like, "OK, time for a new title!" So I was flipping through the book -- when I find titles, I try to find them in the text first -- and there's only one word that's coming up repeatedly. And I passed it over a million times and I thought, you know, you cannot call a book that. That is horrifying. And so I go all over the book, and it's the only thing you can call it. A lot turns on the use of this word. And then I started thinking, you know, this is what a title is supposed to be: a little rough, ideally one word, and something that will get people's attention. And it didn't feel like a cheat because it really is of the book. So I wrote to my agent and said, What do you think of this? And he said yep, and I wrote to my editor, and she said, yep, and then we had this bizarre discussion about whether it should be "Raghead" or "Towelhead." [Laughs] I talked to my [now ex-]husband and he said, "Tell them it has to be 'Towelhead,' because 'Towelhead' is funny. 'Raghead's' not funny. There's whimsy in 'Towelhead.'" [Laughs] It's the stupidest slur! There are better slurs. If you really want a powerful slur, that's not the one you want.

The title is likely to set off alarm bells for a casual reader who doesn't know anything about the book. Did you worry about that?

Sure. It's offensive. I hope the fact I'm half Arab allows me to use that title. Which I assume it does. It's not like I'm some white person who's calling the book "Towelhead." I think that would cause a lot more trouble.

Did you encounter slurs like that growing up?

My brother did. For some reason I didn't. But he was on the crew team in high school and they called him everything. We used to laugh about "sand nigger." We thought that was hilarious, and kind of creative. [Laughs] I don't think he was really disliked, but he did get called these things.

Do you feel any pressure to represent Arabs in a certain way, whether it comes from Arabs or others?

You mean to behave myself more? [Laughs] I should behave, I really should behave. But I clearly can't. When I first started writing the stories for "Brutal," that was when I first started heavily getting into the sexual material. I would write it, and it would be so gratifying. And then I would say, OK, that's enough. You need to shape up and stop writing this smut and write a real, respectable story. So I would try, and it would just degenerate. It got worse and worse, and I thought, well, this is what engages me. What engages me generally is my own shame; I always write from shame. It's the hardest thing that I manage in my life. Part of the way I have attempted to cure it is to write about it. The characters I like to write about are perpetually rejected by men or accepted by men in unacceptable ways, and they have to make do. I guess that I'll always write from that place, and it'll never be pretty. Therefore I will never be able to properly represent any kind of Arab culture because it's the culture that I both appreciate and in some ways [has] brought me all my shame. Just because it is a very specific culture, it's not a sexually open culture.

Having written about politics and anti-Middle Eastern sentiment through the filter of Jasira, do you plan to write about them in a more direct way?

[I'm working on] a second novel, "Hutch," and it's about this guy named Reed Hutchinson. He's an ex-Marine, back from the second Gulf. He has a lot of ideas about Arabs, and has a half-Arab niece who he's extremely protective of. But he's also a violent guy and I don't know what exactly is going to happen with him. But I like writing about Americans' feelings about Arabs. We're so tangled up with the Arabs -- we have always been, but increasingly in the last 15 years, it's astonishing how tied up we are. The thing that fascinates me is that it's becoming more and more difficult for Americans to hate the Arabs because we have proposed to save them. And if you're going to save someone, you're not really allowed to hate who you're saving. It doesn't make sense. I think that Americans culturally would like to feel that we're going to help these people, but also think, "These fuckers are killing our servicemen." "Towelhead" is very much a private thought that Americans could have and feel conflicted about having, whereas on the surface, they say, no, of course they should have democracy, just like us.

Shares