Matt Taibbi writes with the unfettered rage of a man in a bar fight. Modeling himself as a modern day Hunter S. Thompson, Taibbi has carved out a blunt, provocative style in his political writing for Rolling Stone and the New York Press. Taibbi is notorious for his vicious descriptions: He once referred to Tom DeLay as a "balding incubus" with a "Gorgon's gaze" and called Harry Reid "a dour, pro-life Mormon with a campaign chest full of casino money." Throughout his career, Taibbi has purposely cultivated his image as a journalistic bad boy.

His last book, "Spanking the Donkey," was a scathing diary of the 2004 presidential elections that included his recollection of a stoned meeting with Dennis Kucinich. Yet he is perhaps best known for his irreverent 2005 column in the New York Press, "The 52 Funniest Things About the Upcoming Death of the Pope," that seemed to delight in the pope's imminent demise and included such items as "Pope pisses himself just before the end; gets all over nurse" and "Doctor applies fingers to neck to check expiring Pope's pulse. Pope's ear falls off." Several politicians, including Charles Schumer, Hillary Clinton and Michael Bloomberg, subsequently denounced Taibbi's column. At the time, Taibbi argued that the piece "had almost nothing to do with the pope or Catholics whatsoever, and certainly wasn't hate speech," but the resulting controversy led to Taibbi's departure from the paper and the resignation of the paper's editor.

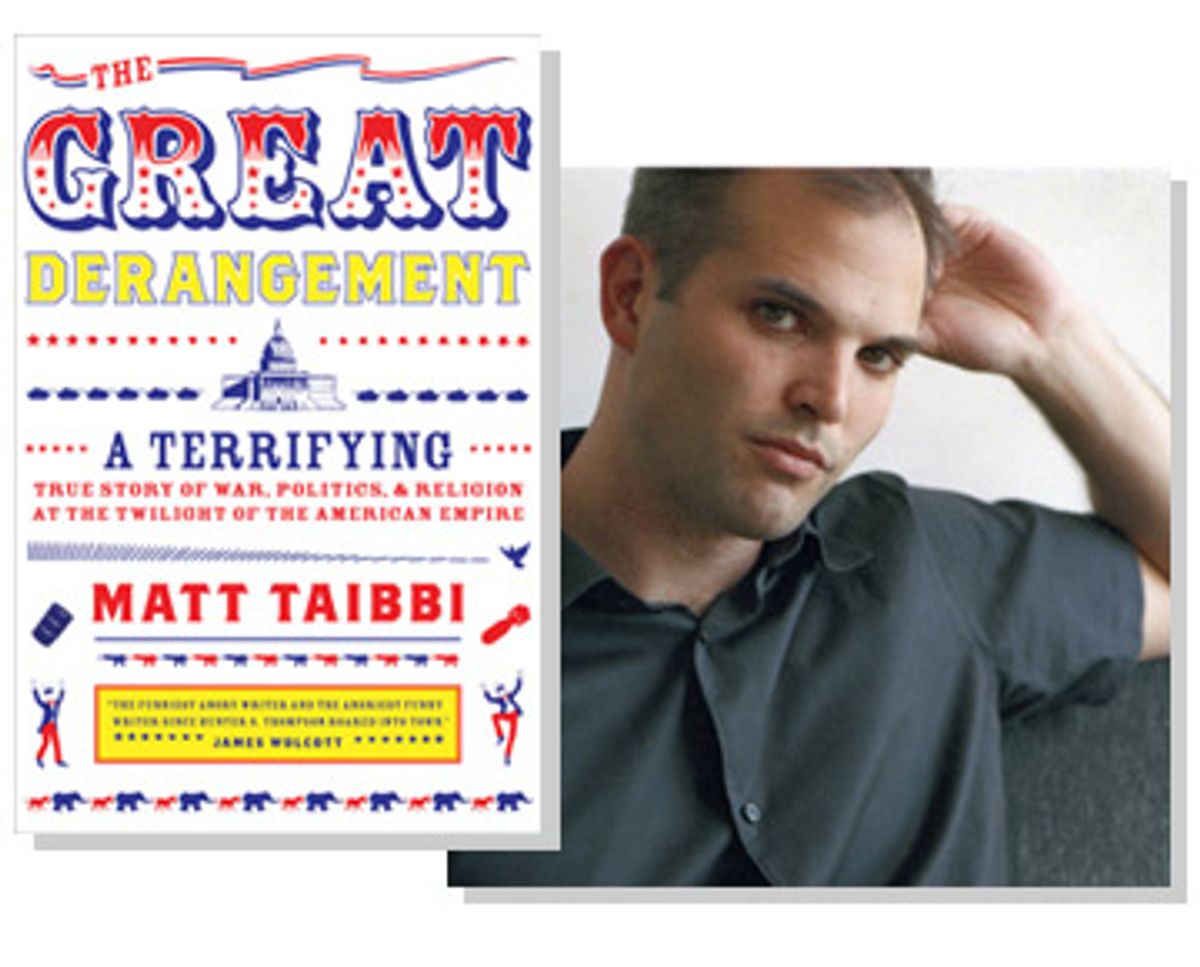

In his new book, "The Great Derangement: A Terrifying True Story of War, Politics, and Religion at the Twilight of the American Empire," Taibbi embarks on a journey through contemporary America, a place that he believes is on the verge of a psychological collapse. Reporting for Rolling Stone, Taibbi goes undercover as a born-again Christian to investigate John Hagee's apocalyptic mega-church. He also documents his contentious experiences with members of the 9/11 Truth Movement, whose conspiracy theories he portrays as leftist parallels to the delusional beliefs of the religious right. Taibbi sees Americans on both sides of the political spectrum reverting to a new tribalism that makes communication and mutual understanding near impossible. In a book that is as darkly funny as it is depressing, Taibbi assails every aspect of modern-day America.

Salon spoke with Taibbi about his book, calling people "retards," and his pessimistic view of America's future.

What does the title of your book mean?

A theme I started to pick up on as I was covering politics for Rolling Stone was this idea that increasingly, we're not really a nation of citizens that have a commonly accepted group of facts that we're debating. Instead we're retreating into these insoluble pockets that have their own versions of reality. In this book, you're looking at, on the one side, the religious right, who sees 9/11 as divine retribution against the United States for sins like being too permissive to homosexuals, and on the other side, on the left, you have 9/11 as this conspiracy that was committed by the United States government against its own people. As people are retreating into these alternative versions of reality, they're unable to agree on anything, and we get this increasingly stagnant form of politics.

In the book, you suggest that this great derangement actually works in the favor of our politicians, because when people trail off into these "escapist fantasies" they don't question the status quo. They focus on irrelevant matters and ignore that their politicians aren't doing what they were put in Washington to do.

Right. It's an ideal situation for a corrupt kleptocracy. What we have now is a situation where politicians get a whole bunch of money from mainly business interests. Then once they hold that office, they spend all their time in office paying back over and over again those campaign contributions through various favors and contracts and that sort of thing. That's really all politics is in this country, it's just a money game.

You really think our political situation is that simple?

Obviously, there's some ideology that comes into it. The politicians do have some leeway to vote their conscience on social issues and things like that. But I've talked to members of Congress and they tell me quite openly that they almost have to start running for reelection again as soon as they get into office.

Who do you think is responsible for this development?

I think the responsibility goes all the way around. A part of this is due to the politicians themselves and a lot of it has to do with the media, certainly, because we don't report any of this stuff.

Why is that?

Because it's viewed as boring. I was in Congress on the day that they passed the final House omnibus appropriations bill a couple of years ago and I was the only reporter in the press gallery when that bill got passed. And we're talking about a bill that basically wrapped up like eight of the 11 appropriations bills into one bill, so you're talking about more than a trillion dollars of public money that was spent and there wasn't a single reporter there to cover it. That tells you a lot about who's paying attention to how the government spends the public's money.

After attending a convention for the 9/11 Truth Movement, you wrote: "The People aren't always the victims in the historical narratives. Sometimes the People are greedy, chest-pumping, ignorant assholes too." So do you think the people who have these "crazy beliefs," as you describe them, bear responsibility for their own ideas?

I'm a product of an East Coast liberal arts educational system. We were all sort of raised in that type of Marxist paradigm where the people are these unwitting victims of the oppressive politicians, but the reality is, if you look at some of the crazy, crazy ideas that are being bandied around nowadays, people have to take responsibility for being that escapist and that unrealistic. It's not fair to pin that all on the media and the politicians. You can spend all your time worrying about whether or not God can reconquer Israel -- if you don't spend anytime worrying about what your congressman is doing with the 50 thousand in taxes you sent in this year, it's your own fault at some level.

For the book, you went undercover to John Hagee's church in Texas and acted like a loyal congregant in order to observe the religious right. While you were at the church, there was an instance where Hagee's son, who's also a pastor, was speaking to the congregation and compared Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to Satan. And you note the tepid response of the audience to that allegation. Instead, what gets people in the church excited is when they're talking about themselves and their own problems.

Absolutely, these people are joining Hagee's church because they're lonely, because they have trouble negotiating their own lives. They need to have some kind of support system. And they need to have somebody to claim to them what the cause of their personal problems are. In the church, they do a very good job of blaming an individual's misfortunes on a lack of faith or Satan or demons. The trade-off for people is, by joining the church, and getting this type of explanation, it alleviates their responsibility to think for themselves. But the danger of that is that they're willing to go along with whatever nutty politics are being pushed on them. What I saw is that these people joined the church for personal reasons, but they ended up supporting whatever the political line was just because it's a trade-off.

Don't you think there's an element of condescension in saying the congregants are using religion to escape from or cover up the problems in their own life? Don't some of the members profoundly believe in God and find that religion serves a positive purpose in their lives?

In the introduction, I say that it's a cliché for the snobbish, urbane writer to go hang around the rubes and pick on them for their primitive ideas. On some level, it's kind of a villainous endeavor. But I tried to be aware of that the entire time and not be condescending in the way I treated these particular people. I tried to make them all out to be whole human beings. In these kind of mega-churches, what's really striking is that there's so little that's like a genuine religious communion. They're more like factories, like fast-food franchises, than they are like churches or communities.

You introduced yourself to members of Hagee's church as someone who'd been abused by your alcoholic circus clown father. How do you think they'd feel if they read your book and realized you'd lied?

I think once they found out I was a reporter who worked for Rolling Stone magazine, it didn't really matter what else I said at that point. I'm already a satanic force. The totality with which they despise anyone who is not religious is really kind of shocking. It's one thing that made it a little bit easier to engage in this kind of assignment that I guess on some level is cruel, because they were always talking about divine retribution and people like me being made to suffer various tortures at Armageddon -- some big God coming down from heaven and having all the people in the ACLU boiled alive.

Right. But you also admit that you found yourself in church singing along to songs and not hating it.

That was a terrifying moment for me. I think I had been in the church for three months at that point. And I remember I came in one morning to church and I found myself looking forward to the music. I had some friends in Houston who I told what I was doing, and I said that if they ever get a call from me that I was flipping, they were to come and have an intervention. And that was the first time I actually thought about pulling that alarm lever.

What's seductive about all of it is that you have a sense of community with these people and like anything else, any other group you become a part of, you start to adopt their values and you start enjoying their company. And so you can see how easy it would be to slide into it. As I said before, a lot of the prejudice and political opinions are really secondary to the action of just hanging around like-minded people.

Don't you see any danger in equating Christians with members of the 9/11 Truth Movement? One is a religious faith, while the other doesn't have a coherent set of beliefs and also doesn't seem to have the same amount of aggression that you describe the leaders of Hagee's church having on matters of foreign policy.

Well, there were so many things about them that were alike. One of the things that's really, really interesting, is how both groups sort of violently disbelieve in the humanity of anybody who is outside the group.

You call it the "Crossfire" paradigm.

Right, yeah, exactly. Basically, if you're not a believer in the Truth Movement, you're someone that's part of a conspiracy, an enemy, whose life really isn't worth a whole lot. The religious right and the 9/11 Truthers are the same in that respect. You should see the vitriol, the letters that I get, for even mentioning anything outside the belief system of the 9/11 Truthers. And this is something I'm noticing again in the Obama-Hillary split now. Members of each group have rooting interests and belief systems and they are completely unwilling to concede anything to the other group and they refuse to debate anything in a rational, calm way. It's all about trying to destroy the other side. The Truthers have a religious belief in their conspiracy theories, in the same way that the other side has religious beliefs in their religion. I understand what you're saying, and it's slightly unfair to compare them, but there's a lot that's the same.

You have a very confrontational writing style and refer to people in terms that some might find offensive, calling some people "retards" and labeling their ideas as insane or crazy. Do you think in writing in this way you contribute to and exacerbate this "Crossfire" balkanization?

My only answer there would be I don't do it just to one side or the other ... And I try to have a narrative voice where people see exactly who I am and what kind of person I am. That makes it easier for them to digest the information that they're getting. If they decide that they trust me, they're going to trust the information that they read, and even if they disagree with me, they at least know where I'm coming from, and that's always a positive. The negative of that is that sometimes you do have language that turns people off. But more often than not, when you use some colloquial language and you talk in the way that someone who was just sitting at a bar or at a dinner table would talk, it's much easier to get your message across to people who don't like reading so much.

At the end of the book, which you wrote well before the current juncture in the presidential campaign cycle, you sound a rather optimistic note, describing the candidacies of Ron Paul, John Edwards and even Barack Obama as harbingers of a "path back to reality." Are you still as optimistic?

No. Not at all. When the Obama campaign really started to pick up steam, I thought "this is really going to hurt the book" because it contradicts the book's premise. Obama's campaign was addressing a lot of the things I'm talking about. It was trying to tone down the kind of tribal instinct that we have in our politics and trying to find a certain common speech where we all try to rationally talk about things and where we all consider everybody, even the people on the other side, just as much of a person or as a citizen as we are. And I think there was a real feel-good vibe about that campaign back in November and December. But now the Hillary-Obama fight has turned into exactly the kind of red-blue, tribal warfare that we've been talking about with Republicans and Democrats and the religious right and the Truth movement. It's the same thing all over again. If you listen to both sides of the campaign argue, they argue with the same sort of religious, hardheaded passion that I'm talking about in this book. And to me that's very depressing. Especially because I have to cover this thing and I'm in the middle of it all the time. And also because I've been friendly to Obama in my pieces and now I'm getting the protests of the Hillary people writing to me all the time. It's the exact same thing I went through with the Truthers.

So do you see any way to get back to a "path to reality"?

When this sort of balkanization of our politics becomes so debilitating that it creates even more serious problems than we have now, then I think the problem is going to get fixed -- probably not before then. In the same way that someone asked me, what's the solution to all this corruption in Congress, with the misallocation of funds and this revolving door of campaign contributors getting contracts? And my answer was, none of it is going to stop until the country becomes so broke that we can't afford to be wasting money like that.

Shares