Daniel C. Dennett is a big man with a big appetite for intellectual fights. A celebrated philosophy professor and the director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University, he is best known for his arguments that human consciousness and free will boil down to physical processes. When theologians, New Agers and other philosophers and scientists complain about scientific reductionism -- the effort to reduce everything, including human behavior and spirituality, to material properties -- they are complaining about Dennett. To which he retorts: "'Reductionism' has become a meaningless code word for 'I don't like that theory.'"

In 1995, with "Darwin's Dangerous Idea," Dennett provoked a firestorm of controversy for insisting that Darwin's ideas are a "universal acid" that "eats through just about every traditional concept and leaves in its wake a revolutionized world-view." Dennett exposed his own worldview in 2003, when he outed himself in the New York Times as a "bright," a fancy new term for atheist. "We brights don't believe in ghosts or elves or the Easter Bunny -- or God," he wrote.

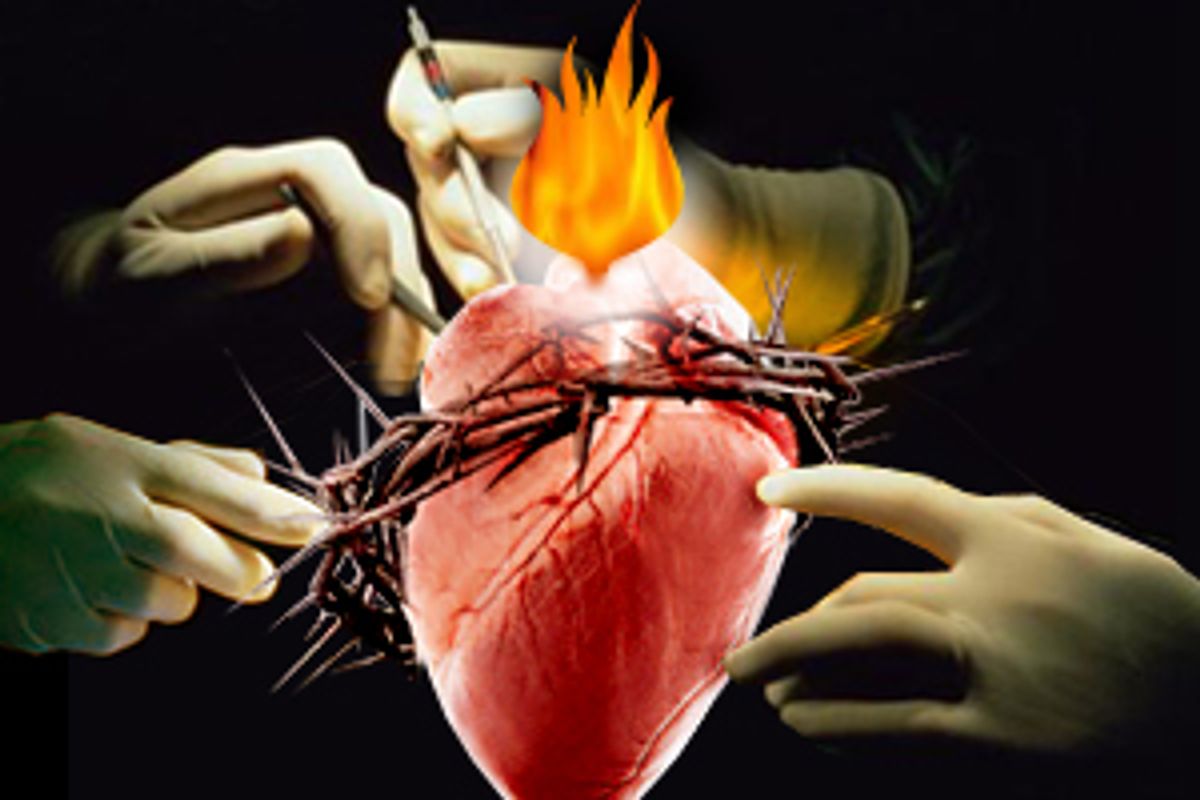

In his new book, "Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon," Dennett provokes readers to examine religion as a product of evolution rather than a transcendental force. Research into religion, he says, should be "based on empirical studies with all the controls in place, just like in medicine," and draw from biology, psychology, history and art. "I appreciate that many readers will be profoundly distrustful of the tack I am taking here," he writes. "They will see me as just another liberal professor trying to cajole them out of some of their convictions, and they are dead right about that -- that's what I am, and that's exactly what I am trying to do."

In person, Dennett is imposing. He is tall, bald and barrel-chested, with a great white beard not unlike Darwin's, although Dennett's beard is better trimmed. He spoke to Salon at the Stardust Resort and Casino in Las Vegas, where he was a featured speaker at a meeting of skeptics. For all his professorial seriousness, Dennett is given to geyserlike bursts of enthusiasm that transform him from Leo Tolstoy to Kris Kringle.

What spell are you trying to break?

I'm proposing we break the spell that creates an invisible moat around religion, the one that says, "Science stay away. Don't try to study religion." But if we don't understand religion, we're going to miss our chance to improve the world in the 21st century. Just about every major problem we have interacts with religion: the environment, injustice, discrimination, terrible economic imbalances and potential genocide. In our own country, the religious attitudes of people are clearly interfering with the political discussion. So if we fail to understand why religions have the effects they do on people, we will screw up our efforts to solve these problems.

Why do you say religion interacts with the world's major problems?

Because people decide what to do, and whom to listen to, and what to take seriously, partly on the basis of their religious convictions and practices. So things that might seem reasonable and attractive solutions may not be remotely feasible without a great deal of carefully guided presentation to those who must live with the policies.

Some people would argue that by dissecting religion you are destroying it.

Yes, some people are afraid that if you look too closely you'll break the spell of religion and make it impossible for people to gain whatever benefits come from it. But I've considered the worst-case scenarios and just don't find this to be a persuasive argument. The cat is out of the bag. The confrontation between religious faith and the modern scientific world is underway and it's not going to stop. The question is, Are we going to carefully and conscientiously study the phenomena or close our eyes and put our fingers in our ears and just go on a roller-coaster ride?

Studying religious faith sounds as futile as studying love. You either feel it or you don't.

The relationship that many people have with religion is basically a kind of love. This has to be appreciated and understood and not denied or belittled. One doesn't interfere with a love relationship lightly. But that doesn't mean that it can't be studied closely. Certainly the wave of research on sex, by Kinsey and Masters and Johnson, was deeply upsetting to many people, who thought it was a bizarre intrusion that should never have been made. In retrospect, though, we learned a lot that has helped us. Sex is as wonderful as ever, or maybe even better, because we've dispelled a lot of really painful and harmful myths.

Many people say they experience God deep within themselves. There's nothing you could say that would convince them otherwise.

The question is whether you'd want to. There's no policy that I've recommended that everybody should be utterly disillusioned about everything. Look at Santa Claus. Am I in favor of banishing him? Of course not. But some illusions really do hurt people, either the people holding them or others. If you have a friend who thinks she is talking to her dear departed husband, and she is paying some "trance channeler" her life savings for this illusion, I think we want to say, "No, you're being defrauded." Even if the illusion does give her comfort.

Are you comparing religious faith to a belief in channelers?

Well, right now we say, "Hands off all that is really religious." But what's that? Where do we draw the line between the scam religions and the real ones? I'm not playing philosopher's tricks and asking for impossible definitions. I'm quite prepared for this to be a political process, where we work out the best way to distinguish them. But if you want to reserve for special treatment some particular practices and traditions, you're going to have to say what they are and why they deserve such special treatment.

Don't you think people's faith in God is more important than their faith in Santa Claus?

Yes, that's why the issue of how, and even whether, to approach such questions must be very carefully addressed. I decided that it was important to explore people's faith scientifically, that the risks we run if we don't are much more pressing than the risks we run if we do.

Are you saying a person is better served by relinquishing his faith in search of a more rational truth about the universe?

That's a very good question and I don't claim to have the answer yet. That's why we have to do the research. Then we'll have a good chance of knowing whether people are better served by reason or faith.

If society doesn't get its moral foundation from religion, where will that foundation come from? What will keep us being good to each other, if not rules laid down by God?

Rules that we lay down ourselves. We've been doing this for centuries. There've been revisions about what counts as a sin in God's eyes. It has changed quite a bit since the days of the Old Testament. It has changed because people thought about it hard and could no longer stomach some of the old rules and practices and changed their minds. It became politically obvious that something had to give, and so it has, and will continue to do so. Now we can continue to expand the circle and get more people involved, and do it in a less disingenuous way by excising the myth about how this is God's law. It is our law.

The political consequences of undermining faith are monumental, spurring riots and killings around the world. Are you -- is science -- willing to take responsibility for these deadly outcomes?

We cannot let any group, however devout, blackmail us into silence by their expressions of hurt feelings whenever they feel that we are getting close to the truth. That is what con artists do when their marks begin to get suspicious, and that is what children do when they can't have their way, and it should be beneath the dignity of any religious group to play that card. The responsibility of science is to safeguard the well-being of those it studies and to tell the truth. If people insist on taking themselves out of the arena of reasonable political discourse and mutual examination, they forfeit their right to be heard. There is no excuse for deliberately insulting anybody, but people who insist on putting their sensibilities on a hair trigger demonstrate that they prefer pity to respect.

Does it worry you that American politics under the current administration have become infused with religion?

It does. The separation of church and state is very important and is not as uncontroversial today in the United States as it should be. Around the world we see clear cases of how seriously bad theocracies are. So we certainly have to take steps to preserve the secular foundation of this country. I put my faith in secular, free societies and democracies like the United States.

You have "faith"?

By faith, I don't mean an irrational belief. I've got to leap and secular democracy is the lifeboat I leap to. Somebody else may think, "If I have to choose between my religion and country," I choose religion. We're beseeching people in Iraq not to do that. But what about at home? It's all right to have an allegiance to a religion, but is your allegiance to democracy and a secular state more important than your allegiance to your religion? If the answer is no, then I don't want you in office. I think that's a pretty reasonable test.

How does President Bush do on that test?

His religiosity seems quite sincere, but it may be more of a political display than a real commitment. I hope he's smarter than he seems! I'd rather he be faking than be deadly earnest about his conviction that God tells him what to do.

What evidence do we have of an evolutionary basis for religion?

Nothing persists in the living world without constant renewal. Religions depend on human brains and bodies just as much as language and music and art do. It has been designed by evolution and human religion tinkerers to thrive in the human environment.

Why does religion have such a powerful hold on us?

Our fundamental instinct -- and this really is in our genes -- is that whenever something surprising and novel happens, we say, "Who's there? What do you want?" That's a very good response to have because maybe what that somebody wants is you. Always being on the lookout is a sort of built-in alarm system that flavors everything we do.

In every culture, people are inclined to personify the forces of nature. What do the weather gods want? What does the sun god want? Out of this bias, built into our nervous systems, comes a machine of sorts for generating ghosts and phantoms and gods and goddesses and goblins and imps. That's not religion, that's superstition. But I think that's part of the biological underpinning of religion.

Are you saying God is a product of our biology?

I'm saying that if God does not exist, many of us would believe in him anyway because of the way we have evolved, both genetically and culturally.

How does evolution contradict the idea of God as creator?

Probably as far back as Homo habilus, there was this sense that it takes a big fancy thing to make a less fancy thing. You never get a horseshoe making a blacksmith, never a pot making a potter, always the other way around. The trickle-down-from-on-high theory of creation is extremely natural. It's a way of seeing the world that is probably built right into our genes.

Then along comes Darwin, who simply shows how all of that design work, all of that creation, can be done by a process that has no purpose, no intelligence and no foresight. It is a very strange inversion of reasoning and it's very upsetting to people to see that something that seems so obvious is being denied. Darwin does away with the reason for believing in a divine creator. This doesn't prove there is no divine creator, but if there is one, it -- he -- need not have gone to all that trouble because natural selection on its own would have created all the biological diversity we see.

Some neuroscientists have isolated spiritual impulses, a belief in God, in the brain's limbic system, the seat of emotions. Do you agree with them?

I think the pioneering work on this is, inevitably, too simple to be true. But there may be something to it. In one sense it is obvious. Everything we believe -- like the fact that the Earth goes around the sun and that Sacramento is the capital of California -- has its signature in the brain. So of course if you believe in God, your brain will be somewhat differently arranged -- at the microscopic level! -- than if you don't believe in God. That just follows from the fact that the mind is what the brain does.

Tell us the story from your new book about the ant and the blade of grass.

Suppose you go out in the meadow and you see this ant climbing up a blade of grass and if it falls it climbs again. It's devoting a tremendous amount of energy and persistence to climbing up this blade of grass. What's in it for the ant? Nothing. It's not looking for a mate or showing off or looking for food. Its brain has been invaded by a tiny parasitic worm, a lancet fluke, which has to get into the belly of a sheep or a cow in order to continue its life cycle. It has commandeered the brain of this ant and it's driving it up the blade of grass like an all-terrain vehicle. That's how this tiny lancet fluke does its evolutionary work.

Is religion, then, like a lancet fluke?

The question is, Does anything like that happen to us? The answer is, Well, yes. Not with actual brain worms but with ideas. An idea takes over our brain and gets that person to devote his life to the furtherance of that idea, even at the cost of their own genetics. People forgo having kids, risk their lives, devote their whole lives to the furtherance of an idea, rather than doing what every other species on the planet does -- make more children and grandchildren.

The capacity of human beings to devote their energy, time, safety and health to the stewardship of an idea is itself a biological phenomenon. That's what distinguishes us from all the other species. We're the only species that can set aside our genetic imperatives and say, "That's not that important, I've got more important things in mind." That uniquely human perspective, unknown by any other species, is a gift of cultural selection.

In an interview with Alan Alda, you said the key to being happy is to find something larger than yourself and work for it. What are you working for?

Truth and freedom. These are terrible times and our ability to destroy the planet has never been greater. But if we can educate each other, listen to each other and learn more about each other -- and as long as we can preserve the free-society traditions of informed political discussions -- I think we have some hope.

Shares