Meryle Secrest describes biography as a "completely selfish enterprise." She's written about the lives of nine artists, including Frank Lloyd Wright, Salvador Dali, Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim, and she happily admits that the process benefits her more than anyone else. Unimpressed by journalistic dispassion, she is complimentary and effusive, calling her subjects "personal mentors." The playwright Arthur Laurents once said that she "oozes sympathy."

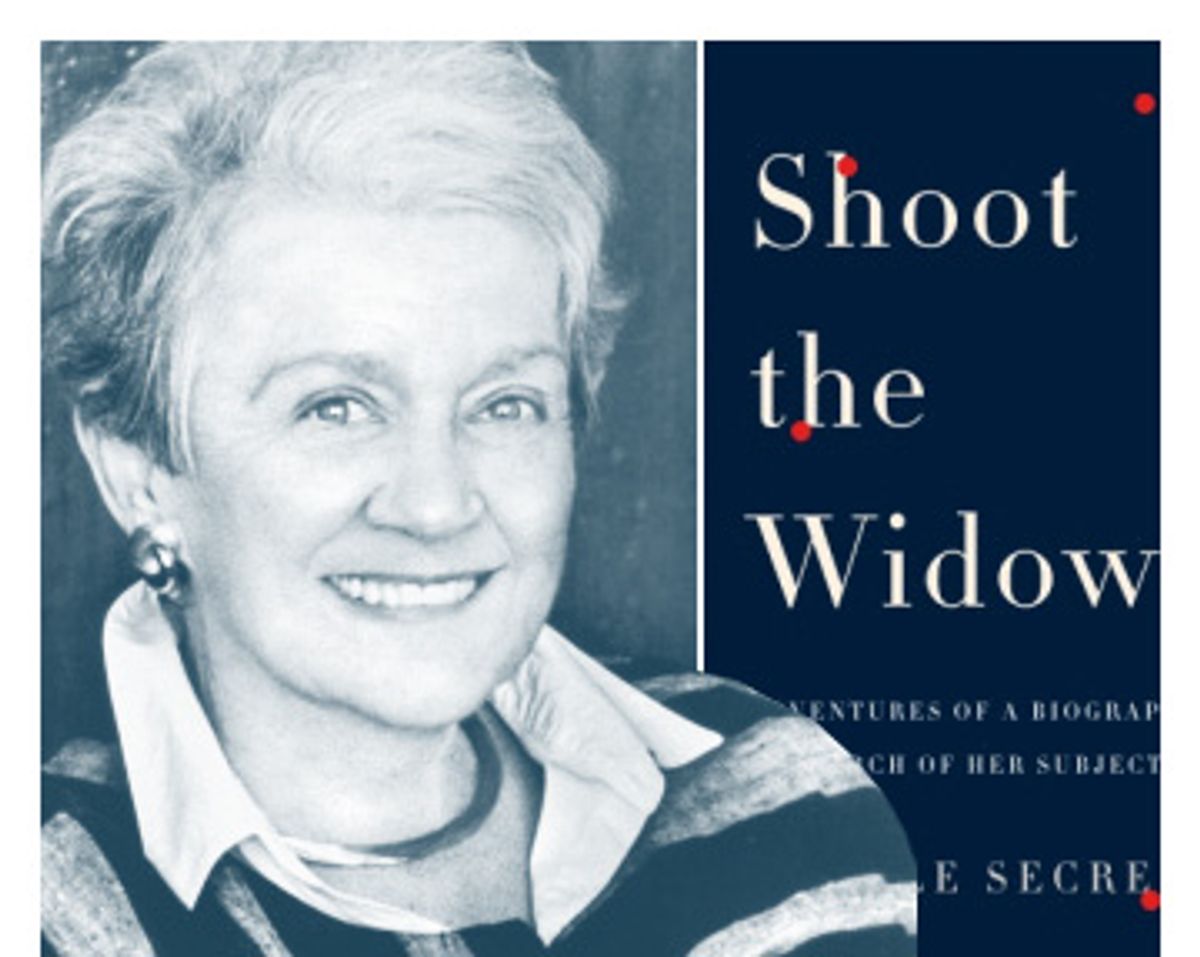

Her most recent book, "Shoot the Widow," is a gesture toward memoir but reads more like biography: To describe her own experiences, she cites her journals and quotes other people as if they were the real authorities on her life. A Pulitzer Prize nominee and winner of the 2006 National Humanities Medal, she spends most of the book detailing interactions with her subjects, particularly failed ones. She finds herself drawn to icy aristocrats who inevitably prove to be fragile and traumatized; she focuses on the vulnerabilities that fuel their artistic success.

Less interested in "thickets of theory" than in Freudian story lines, Secrest speaks in anecdotes and quotes, taking pleasure in 20-year-old strands of gossip. From her home in Washington, D.C., she talked with Salon about her experiences with libel law, psychotherapy, and death threats while often suggesting what "a good next question would be."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

When you wrote about Stephen Sondheim, you became so close to him that you'd accidentally call him by your husband's name. Do you feel it's necessary to develop an almost romantic relationship with your subjects -- whether dead or alive -- in order to write a good biography?

Steve certainly thought that a biography was a kind of love affair. I've fought that idea very hard. In the case of Kenneth Clark, we had established a friendship before I began writing, and he had been very unguarded with me; we didn't have a love affair or anything like that, but we did have a very warm and loving relationship. But all of that went out the window as soon as I tried to find out what he was really feeling.

I'm so against the interview that destroys. It's become fashionable and I'm absolutely opposed to it. I don't feel that I have an automatic right to know what happens in my subject's mind. I dislike the idea of the interview being adversarial. You're either for your subject or you're not.

After the cozy interview process, are you worried your subjects will feel betrayed by what you write?

I haven't done that many books on people who are alive for a very good reason. That should really be your next question: Why not? It's because you have to be ever so careful about libel. I've only done subjects who are alive three times -- Kenneth Clark, Stephen Sondheim and Salvador Dali, who was a very tricky case because he was helping to promote his own forged prints. Generally speaking, you want to write about people who are no longer with us. As it is, I've had death threats.

By whom?

Richard Rogers.

Richard Rogers?

This looks like a harmless business, but someone who knew him said that if I wrote something about him, I'd be found somewhere, in a river. I'm serious. And with Dali I had people threatening to break my knees.

You've said writing biographies is selfish. How has it benefited you?

I would have gone to university if my family had stayed put in England, but when we all moved to Canada [after World War II], my parents couldn't afford it. I always wanted to be an artist; well, now I'm writing about art, at one remove. This is my education -- an advanced education.

In the book you write that if you had gone to college, you would have become a psychologist. Do you see these two professions overlapping?

I've had about 10 years in therapy myself, and that has helped me a lot in dealing with my subjects. But unlike a therapist, I don't stay behind the wall of detachment and impartiality. If someone's putting up their defenses, I might start talking about myself and my own issues. For instance, when I interviewed Katherine Anne Porter, I knew that she'd had a really chaotic private life, so I started talking about the fact that I had just left my husband and was trying to bring up three children -- you know, that kind of thing. The next thing I knew, she was telling me about her abortion.

I think of the interview like a train ride. At the end of the eight hours, you know everything about the person next to you. You try to get them past their natural reticence; but in exchange, you give up yours.

Do you feel you ever really understand what goes on in your subjects' minds?

Well, you start out with the idea that you can't possibly know your subject. Right? You can't possibly know their inner thoughts. So what's the next best thing? The next best thing is a diary, let me tell you. I love diaries. I can never get them because nobody keeps diaries anymore! That's the problem. Letters are the next thing, and if you don't have diaries and you don't have letters, then you've done something really stupid, which is you've set yourself an impossible task. I say this in a wry fashion, you realize, because I'm now writing about an artist who left no letters or diaries: Amedeo Modigliani, an Italian portraitist who died in 1920 at the age of 35.

Were there any subjects you didn't care for? What about Frank Lloyd Wright? You write that he was a "black hole sort of person: You don't want to get too near him or you disappear into a black hole."

There was a point with Frank Lloyd Wright where I could just get no further. I knew why he became an architect, but I could not understand why he became such a brilliant architect. He was the one genius I ever wrote about, and there was just something unknowable about where that came from: This was a man who did everything wrong. His personality was -- how do you put this? -- multiply challenged. And then you look at this sublime work. I never knew what the source for his inspiration was. And perhaps he didn't, either.

How often do you feel that what you write can actually influence the trajectory of the life you are documenting? Stephen Sondheim once lightly accused you of causing his house to catch fire; the children of the British art historian Kenneth Clark blamed you for family strife.

I do know I influenced the Clark family, and it wasn't for the better. The children felt guilty for having talked about mama's drinking, and they were reproached by their father; and their father, who was already in poor health, had a relapse. I wasn't happy about it. If I could do it over, I wouldn't have done the book. It was a mistake.

When you're writing a biography, do you feel uncomfortable imposing yourself on someone's family?

I mean, if anybody ever tried to write about me, I wouldn't cooperate. That's a real confession, isn't it? There is too much about my life that I would be hideously embarrassed about. Having someone write about you is an ego trip, but it's also very scary.

Shares