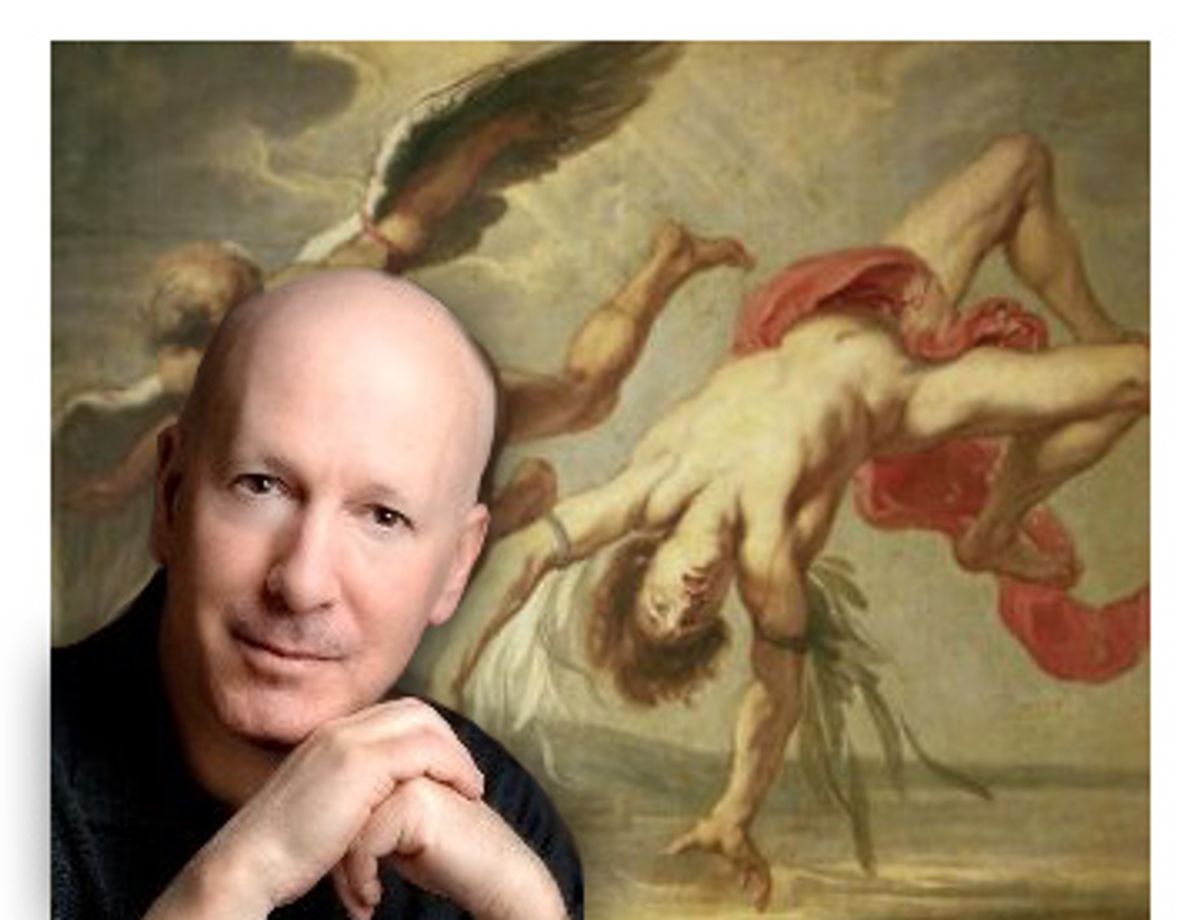

Richard Bookstaber's résumé includes stints as a risk management officer (the guy who strives to keep an investment bank's traders from running wild with their bets) and as a hedge fund operator (the guy who makes the bets). He has worked for some of Wall Street's most famous firms, including Morgan Stanley and Salomon Brothers (now part of Citigroup.) He jokes in his book, "A Demon of Our Own Design: Markets, Hedge Funds, and the Perils of Financial Innovation," that while he didn't directly cause "the 1987 stock market crash and the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund collapse," he was "in the vicinity."

He knows the business. Which means it was probably worth paying attention in April, when his book was published, and he confessed to what many of his Wall Street colleagues would no doubt consider heresy.

The steps that we have taken to make the markets more attuned to our investment desires -- the ability to trade quickly, the integration of the financial markets into a global whole, ubiquitous and timely market information, the array of options and other derivative instruments -- have exaggerated the pace of activity and the complexity of financial instruments that make crises inevitable. Complexity cloaks catastrophe.

Bookstaber is not the first to warn about the risks of financial innovation. But he may be the person most deeply embedded in the belly of the beast. In the crowd he runs with, it is much more common to hear the exact opposite sentiment -- that the vast modern panoply of complex financial instruments -- credit derivatives and collateralized debt obligations and all the rest -- have made the world safer, instead of more dangerous.

At the time Bookstaber's book was published, even though severe cracks in the housing market were readily apparent to anyone who was looking, the conventional wisdom still reigned supreme. The clever minds of the world's financial markets had devised a system in which risk was chopped up into millions of tiny pieces and redistributed -- dispersed -- all over the world. As a result, the overall financial system was supposed to be more stable, less prone to collapsing because of any one shock.

But with each passing day, the vast gaping holes in that theory become more apparent. The latest news -- on Wednesday Morgan Stanley alarmed the market with the announcement that the investment bank was writing off an additional $5.7 billion in losses. The bad news just keeps on coming. The biggest players on Wall Street have been stumbling and lurching all fall. For months, the stock market has lunged between schizophrenic polarities of hope and fear. No one knows how high the final toll will go -- estimates range into the hundreds of billions. Top executives have lost their jobs, millions of Americans are losing their homes, and the end is not in sight. The so-called credit crunch is now spoken of in somber terms once reserved for the savings-and-loan crisis and possibly even the crash of 1987. State-of-the-art financial wizardry has turned out to look an awful lot like a game of three-card monte. Instead of making us safer by spreading risk around, we appear to have been made more vulnerable by the placement of risk into the hands of people who couldn't evaluate it and can't afford it.

Bookstaber's basic thesis borrows a concept drawn from a particular strain of engineering analysis. We have designed a system that is too "tightly coupled" he says; we have a built an incredibly complex but fundamentally fragile machine where if one thing goes wrong, the whole system sputters to a halt. When what we need, instead, is a loosely coupled system that can withstand shocks without crumbling. Such a system might not be the most efficient, but it will get the job done.

We should be more like the lowly cockroach, he declares, a humble beast that is optimized for no environment but has managed to survive in all.

Bookstaber spoke with Salon about the issues raised in his book.

If timing is everything for a trader, then you nailed it with "A Demon of Our Own Design." Did you imagine back in April, when your book came out, that by October you would be testifying before Congress, giving your opinions on how government regulators might have been able to prevent the current mess?

I knew as I was writing it that the same sort of problems that had happened before would happen again. It was fortuitous for me that it happened right as the book was being published. The subprime crisis is sort of the poster child for the issues that I talk about it in the book.

Your basic argument was that Wall Street's addiction to financial innovation may precipitate economic disaster? Did that happen? Are we living through a catastrophe?

I don't think I use the term "disaster." I try to talk about crises. The crash in 1987 was a crisis. Long-Term Capital Management was a crisis. What we are seeing now is a subprime/mortgage/credit crisis. Now, a crisis could turn into a disaster. The question is whether this crisis breaks what you might think of as the blood-brain barrier between the financial markets and the real economy. That did not happen with prior crises and it remains to be seen if it happens in this case.

On your blog, you observed that every time Wall Street goes through one of these crises, and the trouble doesn't spread to the real economy, we only end up being set up for bigger problems, because traders and banks are encouraged to engage in more of the same behavior that created the crisis in the first place. But many of your colleagues would argue that the reason these intermittent crises haven't metastasized into a full-blown catastrophe is precisely because all these new financial products have dispersed risk so widely that no single setback can take down the whole system.

You can sort of have it both ways. Earlier this year [Federal Reserve chairman] Ben Bernanke said hedge funds were valuable because they provided liquidity, and by providing liquidity they actually reduced the volatility of the market, which makes sense, in that if somebody needs to buy something or needs to sell something and there are a whole lot of people sitting there ready to grab it, the market doesn't have to move too far. Similarly, derivatives often have value because they allow people to break apart risks and pass the risks on to people who are more willing to take them.

You can say both of those things, and then still say the sort of thing that I'm saying, which is that, from day to day, you may see lower volatility and more liquidity by having hedge funds and derivatives out there but you also have an increased probability of market crises. So, ironically, you can have reduced risks day to day, but you create a higher risk of major dislocations. And similarly, you can look at each individual derivative and say, yes, this adds value, yes we should have this derivative, but in aggregate you end up with a more complex market, and that complexity makes the market more crisis-prone.

But at the same time, many economists would argue that as far as the real economy is concerned, during this same period of increasing complexity we've been living through what they call "The Great Moderation" -- a period of generally low inflation, relatively mild recessions, etc. So why should we care what goes on in the financial markets? It almost sounds as if, to borrow your own phrasing, the real economy is only loosely coupled to financial markets. If that's true, why should we be worried when a bunch of traders lose their shirts?

You could argue that if this is the game these guys want to play, let them play it. OK: We get some sort of a crisis in the financial markets and the players in that market get hit but it doesn't seem to affect the overall economy so whatever they do is fine. But some of the people that are hit are innocent bystanders in the market. There is collateral damage; there is somebody that sees their portfolio shrink in value. So it isn't as if it is just being played by a bunch of grown-ups who are playing only against one another. The second reason is that while up to this point we haven't seen the spillover become systemic, it could become systemic, and the current crisis may be one where that happens.

Is that the kind of cautious attitude that a risk management officer needs to do his job?

If you are a risk manager, all you care about is the risk to your institution. If all the world is self-destructing, but we're making money, I've done my job. Now if there were sort of a United States government risk manager, that would be a different matter.

Wouldn't that be Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke?

He would be the most natural person to take on that role. The problem right now is that a lot of the problems that occur in the market are outside of the control of the tools that the Federal Reserve has. As I mentioned in my testimony to Congress, even a lot of the data that is required to evaluate the risk is not available to the Fed or, as far as I know, any other regulators. There are at least two things that it seems clear we need to know: What's the level of leverage for different types of hedge funds and has it been growing or reducing? Leverage is one of the key characteristics that leads to tight coupling and market crises.

What do you mean by leverage? How does that work?

Leveraging basically means that you borrow money. If you have a billion dollars of capital, instead of buying a billion dollars' worth of assets you can buy $2 billion or $5 billion worth. One way you can do that is by going to a financial institution and saying something like this: Let's say I'm a pure equity fund, I've got a billion dollars of stocks, these stocks are all liquid, that is, they will all be easy to sell if you have to sell. So why don't I give them to you to hold as collateral, so that if things go wrong you have a claim to these stocks and you can do what you want with them. And you lend me $3 billion, I use that $3 billion to buy more stock.

And the problem with that is, when the bets go wrong, the damage done is magnified by the amount of leverage that exists in the market? And because complex financial instruments like derivatives have tied all the market players so closely together -- everything is so "tightly coupled" -- the damage spreads throughout the entire system. So a prudent regulator should be able to set limits on how much you can be leveraged?

Well that's how we got Regulation T after the crash in 1929. A normal person can't leverage more than 2 to 1. But what we need to know is how much the big players -- the hedge funds and so on -- how much they are leveraging and what they are leveraging.

Wouldn't knowing that reduce the competitive advantages of the traders against each other? Isn't that the kind of information that they don't want anyone else to know?

No. First of all, as a regulator, you want to know in general what's going on. Think what happened with the quantitative funds that had major problems in August -- some of them dropped 20 or even 30 percent. Nobody knew how leveraged they were; nobody knew how leveraged they were versus one or two or three years prior. After the fact, I think a lot of people were somewhat amazed by the extent of leverage, and that high leverage is what precipitated the crisis for those funds.

Maybe if it was public knowledge that these hedge funds used to be leveraged 2-1, then the traders said "last year we weren't making very good returns so we decided to leverage 3-1, and now we're leveraged 6-1" -- maybe a lot of people would have said, whoa, that sounds pretty risky, I'm not sure I actually want to be invested at that level of leverage. And there might have been regulators who started to say that with that degree of leverage, it wouldn't take much of a bump on the road to force liquidations that could cause trouble for the market.

You could argue that humans, by nature, generate complexity. How do you reverse that? How do you return to a state of simplicity?

There is a tendency we have to take the environment as we know it now, and think this is it, and construct things that are ideally suited to the current environment. The problem with financial markets is that we also know they can change in unexpected and unanticipated ways. My argument is that you want to construct the markets and construct the way you behave in the markets so that if the world tomorrow is exactly like the way it is has been for the last year, maybe what you are doing is not optimal. But if things change in surprising ways, what you're doing is more robust and there is a higher probability that you will do well in the long run.

Taking the cockroach as an example, as we look back hundreds of millions of years, we have jungles that became deserts, and the deserts turned into cities, and if somebody looked at the cockroach, it never would have won the Best Designed Insect of the Year award, because it's very simplistic in what it does. So in any one environment people would point to the cockroach or point to the market that was behaving the way that I would argue we should behave, and say: You're ignoring what's going on right now, you're not fine-tuned to the degree that you could be to do the best possible job in the present market.

But that's kind of like somebody saying: Hey, in this particular jungle there is a seed that is really abundant and unless you have an insect with a mandible that is designed in this particular way you can't really optimize on the abundant seed. But that insect doesn't survive if the environment changes and the plants with those seeds disappear.

But isn't that like being a value investor when a bubble is happening? All the speculators make a ton of money and you sit there with your long-term robust strategy losing money.

I can't argue that total simplicity is best, but my guess would be that right now we are erring on the side of being overly fine-tuned. But that's kind of a metaphysical or philosophical argument. A less abstract way to look at it is that complexity and tight coupling born of leverage make the market more crisis-prone. So if you want to reduce the crisis-prone nature of the market, as a regulator you've got to reduce complexity and you've got to reduce leverage. And in the financial markets, complexity means derivatives and structured products and innovative securities.

Some are arguing that the market is already doing the job of fixing its own mistakes. That after having been burned on subprime-linked collateralized debt obligations and structured investment vehicles, the big Wall Street players won't make the same mistake again. They'll just move on to something else. Couldn't that be construed as a normally healthy system working as it should?

Well, you know, the next crisis is always different. I think what I've tried to identify in my book is not so much how do we predict the next battle, or the next crisis, but what are the underpinning characteristics that lead us to stumble from one crisis to the next?

How do you judge the current crisis? The markets seem to flip almost every day between thinking the worst is behind us and disaster is around the corner.

There's incredible volatility now. People don't quite know which way to go. But before I answer that question I have to preface it by saying two things. One is, I'm a pessimist by nature; that's probably why I've been good at risk management. Secondly, I don't think that I'm that great a prognosticator. I don't think that I'm the kind of guy that I would talk to about where markets are going. Having said that, I do think that there is potential that this could be a very unusual crisis. Usually when we think of a market crisis we think of things that go boom, that sort of blow up, and then dust settles, and five months later it's back to normal.

But the current crisis could be different. It could be so long term that we could be in the middle of it and not really realize it. A great analogy for this is what happened in Japan, with the equity markets. A whole generation of people in Japan have grown up thinking that stock markets don't move because for 17 years or so the Nikkei has been bouncing around in the same trading range and hasn't gone anywhere. I'd call that a crisis. An equity market that is the same place 20 years later that it was before is the same thing as having an equity market that over the course of one year drops 50 or 60 percent and then just slowly crawls out from that pit.

So it may not even be that we see housing prices plunge 30 percent or 40 percent. It could just be that the housing market, which we have always thought of as not just being a store of wealth but something that appreciates, instead sits and stagnates or doesn't do anything for a number of years. And that would be a crisis that took place over a period not of months but of years. It could be a real slow burn.

Shares