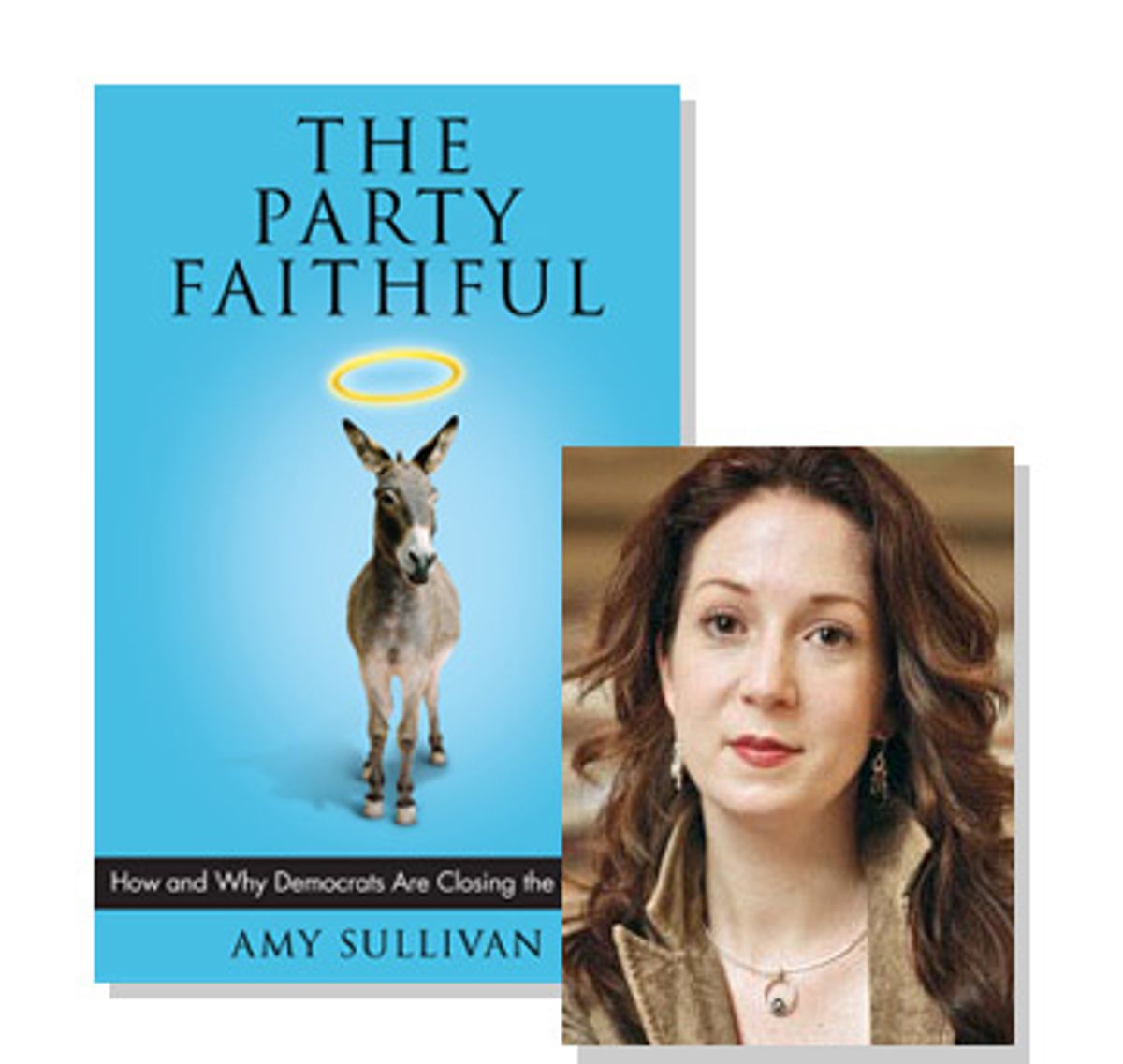

Amy Sullivan is a senior editor at Time, a liberal Democrat, and an evangelical Christian. One of those things is not supposed to be like the others, but she argues in her new book that her fellow Democrats need to reach out to her fellow evangelicals if they hope to build an electoral majority. In "The Party Faithful: How and Why Democrats Are Closing the God Gap," Sullivan describes how Democrats like Gov. Jennifer Granholm have won over white evangelical voters without changing sides on such hot-button issues as gay marriage and abortion. Sullivan spoke to Salon about the importance of language in reaching out to evangelicals, the supposed decline of the religious right, and why Democrats should court religious voters when they are doing so well among an even-faster growing demographic: people with no religious affiliation at all.

You were raised a Baptist, but you now prefer to call yourself an evangelical Christian?

Yeah. I guess I prefer "evangelical" because I, for years after high school, kind of bought into the spin that I [describe] in the book, that Democrats and Republicans alike have, which is conflating evangelicalism with conservatism. And I thought, "Well, I don't have politically conservative beliefs, so I must not be an evangelical." But I didn't turn my back on religion, and it was in the course of 10 years, in exploring more mainline Protestant traditions, that I really got in touch with what made me an evangelical. It has nothing to do with whether I cast a vote for a Republican or whether I think of myself as pro-life. It has everything to do with the fact that like most evangelicals, I rely more on the teachings of the Bible than the teachings of a church. It's very much a personal relationship with God, a personal interpretation of biblical teachings. And -- I write this in the conclusion of the book -- it wasn't until I went out to a Christian music concert to cover it, when I was standing in this crowd of 15,000 evangelicals, really holding lights in the darkness, that I looked around and realized, I am one of them. And I need to stop ceding that label to conservatives. Because the only way the stereotypes will go away is if more of us stand up and reclaim that and kind of come out of the closet as evangelicals.

You're pro-choice. Does that interfere with being an evangelical?

Well, I don't like the [pro-choice] label. I guess the reason I wrote about abortion the way I did in the book is because I have serious moral concerns about abortion, but I don't believe that it should be illegal. And that puts me in the vast majority of Americans. But unfortunately, there's no label for us.

Do you support gay marriage rights? And are you a biblical literalist?

No, I don't take every word of the Bible literally. I do believe in gay rights. And in fact very strongly. And I think that you'd find a surprising number of evangelicals feel the same way. But we don't get the press that other evangelicals do.

You mention in the introduction to "The Party Faithful" that part of what led you to write it was a recent incident in church. The pastor told the congregants that they had to vote Republican to be in line with God's wishes. When you were growing up, did you have pastors who were open political partisans?

Many of them might have been Republicans, but you would never have heard that from the pulpit. They didn't see it as relevant to what was going on in church. Church was all about what was going on with your soul. They focused on saving your soul. That changed probably sometime in the mid-'80s. And tragically, it went along with the rise of the religious right. Pastors began to get more political. Congregants got more political. When I was 10, I remember very clearly we were pulled out of Sunday school one week because one of the women in the church had put together a workshop for us on abortion. And she talked about marching at abortion clinics and protesting and blocking the entrances to clinics. And through all of this, I think my saving grace was that my parents were two very liberal Democrats. Even though they didn't explicitly say, "Don't pay attention to this," I think I had more of a questioning bias than other adults did in the church. So when people said there were people who go around and enjoy killing babies, I wasn't quite right with that idea. It can't be as simple as that.

The argument at the center of your book is that Democrats need to stop conceding the evangelical vote to Republicans. And you cite the Kerry campaign in 2004 as an example of the negative consequences when Democrats ignore the evangelical vote. Then you give the example of Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm, who has deliberately reached out to religious voters, as a model for how Democrats can run and win. So in your opinion, what are the main things Democrats should do to win the evangelical vote?

The biggest thing Democrats can do is to recognize that evangelicals can and do vote for them. Sixteen million evangelicals voted for John Kerry in 2004. So, to write off the entire constituency from the beginning is to ignore people that are already on your side. And obviously it makes it much harder to add to that total. So absolutely the biggest thing is to recognize that evangelicals are already part of the ranks of the Democratic Party. I point out Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, two evangelical Democrats. So that's not an oxymoron. And the other things are not a matter of pandering to evangelical voters.

You touch again and again on the issue of abortion and give examples of how Democrats can augment their appeal with religious voters just by subtle shifts in language. You write how some Democratic candidates are using the phrase "abortion reduction in addition to choice" when they discuss their positions. But isn't this just a form of clever marketing? Doesn't it obscure whether or not a candidate believes abortions should be legal?

None of these candidates suddenly start hiding the fact that they're pro-choice. No one who voted in Michigan was confused as to whether Jennifer Granholm supported a woman's right to have an abortion. What some Democratic candidates are doing would in fact just be clever marketing if it wasn't backed by policies that are being proposed right now in Congress to reduce abortion rates. There's really no argument about whether it would be a good thing to reduce the abortion rate. That's been something that's been standard policy with the choice groups in addition to everyone else for decades. The problem is, I've been talking to these folks for a long, long time, and they say, "Of course we want to reduce abortion! Don't people know that?" And I say, "No, they don't know that. And you don't get any credit for it if people only hear you talking about a right to choose."

If you take a group like Planned Parenthood, 90 percent of their efforts are on reducing unplanned pregnancies, and yet when they looked at the materials that were going out, 90 percent of their message was about abortion and a woman's right to choose, and they said to themselves, "There's a good reason people don't know what our work really is. And don't know that a very small percentage of what we do is related to abortion." So, I think you can call it marketing, but I think that's cynical, because I think it's more appropriately public relations to let people know what Democrats really stand for and what liberals really stand for when it comes to abortion. The thing I always come back to is, Republicans take for granted that their base knows that they're pro-life and they're not moving on that. And so the people Democrats need to speak to are those people in the middle who are kind of queasy about abortion but who don't want to see it outlawed. Democrats never mention reducing the abortion rate or the rate of unplanned pregnancies, and so they lose that opportunity to reach out to voters who are less sure about their position on abortion.

You suggest that Democrats should really emphasize this desire to keep abortions rare. But do you think these efforts will appease evangelical voters who firmly believe abortion is wrong?

You're never going to win over all evangelicals, and I don't think anyone has suggested that. But 40 percent of evangelical voters are politically moderate, and when you dig deeper into that, you find that abortion is not their key issue. They're very willing to vote for a candidate who differs with them on abortion. We did a poll at Time in November on this and we found that when we asked people that very question -- would it be possible for them to vote for a candidate who didn't support their view on abortion? -- very high percentages said not only that they could but that they did vote for these candidates.

In the book you frequently cite that statistic: 40 percent of evangelicals are moderates. Do they define themselves as moderates, or is that label based on polling data?

It's based on some fairly consistent polls that are done a couple times a year by the Pew Research Center. [They use] a battery of questions that ask people about their political beliefs and then a battery of questions that ask people about their religious beliefs. They [also] come up with categories of evangelical liberals, which are about 10 percent of the population. In some polls it's asking people to self-identify, and then in some polls it's developing categories based on their responses. These are folks who want to protect the environment, who want universal healthcare even if means having to higher taxes for it.

Moderate evangelicals have been voting with the Republican Party by default, because it was the one party that was speaking in terms of values. I always try to remind people that Republicans have been presenting solutions to moral problems. It doesn't mean that they were good solutions. Or the right solutions. But they were presenting solutions and they were acknowledging that the problem existed.

But what about the other 50 percent of evangelicals who aren't moderates or liberals? Do you think Democrats should campaign to them as well?

Instead of coming up with a strategy to micro-target different groups in the electorate, I really think it's just adjusting the path overall where they have refused to talk to any of these voters in the past, as when I talk in the John Kerry chapter about the field director who says, "We don't do white churches." Well, white churches are 75 percent of where your voters are. So if you don't go into white churches, you're not talking to conservatives or moderates or anyone else.

So I guess I think that those types of approaches aren't geared toward picking off a few voters here and a few voters there. They're geared toward changing the perception about the Democratic Party. And in some cases that perception was unfair and unearned by Democrats. And that was a result of Republican spin and conservative spin. But in some cases, there's something to it.

When you write off Catholics and evangelicals as not your voters, you're stereotyping. When you make fun of John Ashcroft or George W. Bush for praying, you are giving off a sense that there's something wrong with that. That there's something ridiculous about people who spend their mornings with prayer. And we've seen this in the polling data as well: When we ask people if they think Democrats are friendly to people of faith, only 29 percent think that now. And those numbers were in the high 40s and 50s a few years ago. So whether it's a result of Republican spin or failures the Democrats have had themselves, the end result is they're being seen as hostile to faith and they're not getting all of the religious voters who really should be with the Democratic Party.

If you could be getting voters and you're not simply because you're appearing to be antagonistic to them, why wouldn't you make the changes, even if you think they're cosmetic, to win those voters back?

Do you think that by making those changes they risk alienating the party's liberal base? That if there's such an emphasis placed on making abortions rare that liberal voters might not be certain whether a candidate is really pro-choice?

I just go back to the comparison with the Republicans. The Republicans have a base who give them credit. They don't have to explicitly say what their positions are just to reassure the base. That then gives them an opportunity to talk to people in the middle. It may be that some voters in the Democratic base continue to want to have these things articulated very explicitly to them by Democratic candidates. If so, then I think they're going to continue to get the same results.

On the issue of gay rights specifically, where many evangelicals believe that according to the Bible homosexuality is a sin, how can Democrats who believe in gay rights and support a gay marriage amendment appeal to evangelicals and to the liberal base?

Well, one thing with this issue is that it's very closely related to age. So we see with younger voters, evangelical and non-evangelical, that the issue of gay rights and gay marriage is much less of a controversial hot button to them than it is to their older counterparts. Democrats have been smart to recognize this. That said, again, I would point you to the elections in 2006 and those in Michigan and Ohio, where you had not just two pro-choice candidates running for the position of governor but two pro-gay rights Democrats, and they were both able to win nearly half of the evangelical vote ... There will always be evangelicals who will never vote for a pro-choice candidate, but you're also going to have a pretty large pool of voters who just don't want to have someone call their personal beliefs right-wing and intolerant. They're willing to set aside those beliefs and vote for someone with whom they disagree on those issues. They just don't want to be ridiculed for them.

Do you think the practice of pastors voicing political beliefs in church has tapered off recently with the evident failures of the Bush administration? Are pastors more wary of openly supporting a candidate in church?

I think it's certainly true that a lot of conservative Christian evangelicals are feeling burned by the Republican Party. They're starting to feel that it doesn't make a lot of sense for them to put all their eggs in one basket. At the same time, a lot of religious liberals who are starting to become much more active look at the religious right as a cautionary tale and they don't want to become the same in the Democratic Party. So I think they're much more cautious about becoming explicitly political in church. Not to say that people aren't political, but it's not greeted with the same openness as it was a few years ago.

After the 2006 election, many in the media declared that the age of the religious right was over. But evangelicals are showing up at the polls again this year, even when other Republicans aren't, as shown in the primaries and caucuses in Iowa, Kansas, Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas and Tennessee. The winner of those contests, Mike Huckabee, a Baptist minister, outlasted every other major Republican contender except the likely nominee, John McCain. Do journalists and pundits actually have a good grasp on how evangelical voters think? It seems to me like they're engaging in projection and wishful thinking.

Certainly, there's a tendency to prematurely declare the death of the religious right. Pretty much every other year there are magazine headlines that either say the religious right is resurgent or that the religious right is over. That's a journalistic shortcoming. And you're right to say that much of that has to do with a lack of familiarity with the community, I think. But there's an important difference here between the leadership of the religious right (and you'll notice that [few] of them have come out for Mike Huckabee...) and the evangelicals in the pews, who may not, or most of them may not, think of themselves as part of the religious right. There are certainly those conservative voters who are frustrated with the Republican Party over the last few years but they're responding to Mike Huckabee because they see him as one of them, and importantly, not one of the Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, James Dobson crowd.

According to the Pew Research Center, in the 2006 midterm elections, Democrats soundly defeated Republicans among secular voters, winning the vote of those who seldom or never attend church by 2 to 1. And according to a study conducted by the Barna Group, since 1991, the number of adults who do not attend church has nearly doubled, rising from 39 million to 75 million in 2004, while the entire adult population has only increased by 15 percent. Why is so much attention paid to the Democrats' so-called God gap when so little is paid to the Republicans' inability to appeal to secular voters? Can't the Democrats win now and in the future by appealing to secular voters?

There was a study done in the fall of 2006 down at Baylor University that was very useful because it actually probed this question. We have seen a rise in the number of people who state they have no religious affiliation. That's not the same as people who identify as atheists or secular. It's just people who don't name a religious affiliation when asked in a poll. And what the people at Baylor did is probe that and try to find out how many of those people really should be accurately categorized as having no religious traditions. And what they found was that a significant percentage of people who said they had no religious tradition still engaged in what we would define as religious practices. They pray every day; many of them say they believe in God; a good number of them, when asked, could identify a house of worship. So I think what it's telling us is that religion is getting a bad rap. And it's getting such a bad rap that it's becoming something people don't want to affiliate themselves with.

But there's no question that the percentage of Americans who are more secular has grown in the last two decades. There are two important sociological reasons for this, and I'll bore you with this because I'm a reformed sociologist. First, you're starting to see the first cohort of kids who are secular and who were raised by secular parents. So it's not as if they were raised in a religious tradition and rebelled against it. They're second generation. And we've never really seen that before.

The second thing is just simply that the cohort of people who are not yet married or not yet with kids continues to grow, and there's a life cycle effect. We know that people stop going to religious services when they start going to college and when they're young adults. But they almost always go back once they get married and have kids. People seem to still think it's important to raise their kids in a religious tradition. But whereas, a generation or so ago, people would start having kids in their late 20s, now they're not having kids until their 30s. So it's just a simple matter of that cohort of childless Americans [being] much larger. But from everything we've seen, they continue to go back to church.

So just to bring it back to your question, I think it's inaccurate to look at the numbers and conclude that a growing number of Americans view religion as irrelevant to their lives. We know that's not true. There's a very consistent number, around 85 to 87 percent of Americans, who say that religion is an important part of their lives. And the demographic trends are actually moving in that direction because immigrants tend to be the most religious of those people in America. So for all those secularists who may be moving up into the ranks of the electorates, they're being outweighed by immigrants, particularly first-generation Asians and Hispanics, who tend to be much more religious than your average white voter.

Throughout the book you mention how deeply religious many Democrats are. You write that two-thirds of Democrats attend worship services regularly. And you show all these Democrats such as Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, John Edwards and John Kerry who are very committed to their religious beliefs. Do you think that many Democrats underestimate just how religious many of the members of their party are?

Absolutely. It continues to shock people when I talk to Democratic audiences and I remind them that 87 percent of Americans say that religion is an important part of their lives. And that includes a heck of a lot of Democrats. Republicans are not getting 87 percent of the vote. I continue to meet people who insist, and these are hardcore Democrats, who insist to me that Bill Clinton is not religious, that it's just an act, that he had to go to church to put off his Republican critics and that he's really not a religious guy. Who find it inconceivable that Nancy Pelosi is a committed Catholic, [or think] that whenever she talks about faith now it's just the result of advisors and consultants telling her it's smart, when in fact this is a woman who's been quoting the Bible in closed-door meetings for decades. So I do think Democrats are kind of surprised to learn who the religious are in their midst and I think those are mostly the secular Democrats. The religious Democrats who I talk to are somewhat relieved because they had all been thinking that they were all by themselves.

How do you see evangelicals voting in this fall's presidential election?

I see evangelical voters voting the same way that everyone else does. They have serious concerns. They are concerned about the economy. They are concerned about not being able to provide healthcare for their families. They are concerned about the war in large part. And increasingly they're concerned about our place in the world. Like what we're doing to combat third-world poverty, what we're doing to protect the environment. The reason that I was writing about whether Democrats can become more savvy or aware of religious voters, is not to put religious issues on the agenda. It's to take them off ... and in so doing, focus on the issues that all voters really care about.

Shares