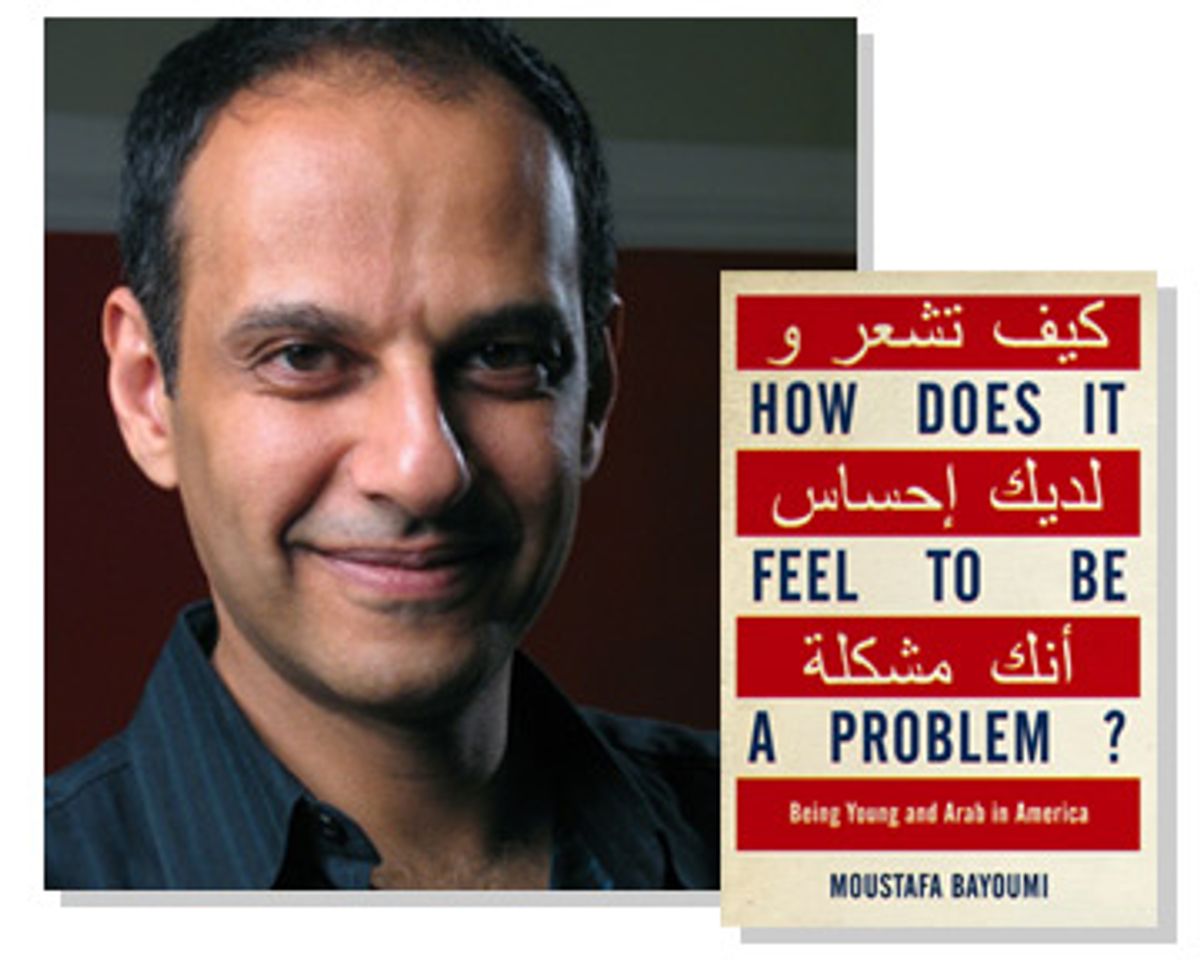

The question posed by W.E.B. DuBois in his classic "The Souls of Black Folk" cut to the marrow of what it was like to be black under Jim Crow. Now, more than a century after DuBois penned his query, Moustafa Bayoumi thinks it is appropriate to ask it again. The associate professor of English at Brooklyn College argues in his new book, "How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?" that young Arabs and Muslims are America's latest "problem."

In a few destructive hours on Sept. 11, he writes, the groups went from being just another set of minorities in our multicultural patchwork to "dangerous outsiders" in many Americans' eyes. Hate crimes spiked 1,700 percent against Arabs and Muslims in the months after the terrorist attacks and thousands were detained, questioned and deported. A 2006 USA Today/Gallup poll found 39 percent of Americans believed all Muslims --including U.S. citizens -- should carry special IDs.

"We're the new blacks," a Palestinian-American in his 20s tells Bayoumi as the young man puffs on apple-flavored tobacco in a hookah lounge. "You know that, right?"

In "The Souls of Black Folk," DuBois aimed to pull back "the veil" separating whites and blacks by presenting a full view of black life. In his new book, Bayoumi gives us seven richly observed vignettes of the lives of young American Arabs and Muslims who live in Brooklyn; he hopes to cut through the suspicion and fear they face as they navigate post-Sept. 11 America and come of age.

Bayoumi's subjects are more ordinary than extraordinary, but that is precisely the point. In the war on terror, he argues, Arabs and Muslims have been reduced to two types: the exceptional, assimilated immigrant and the violent fundamentalist. Bayoumi hopes to humanize, as well as complicate, our view of Muslims by presenting his subjects in the texture of their daily lives with all of the attendant humor, boredom, messiness and small victories and defeats. That does not mean the book is prosaic -- suspicion, fear and being different create roadblocks and tough choices in every chapter.

Among the stories Bayoumi tells are those of Sami, a U.S. Marine who is deeply angered by Sept. 11 and the war in Iraq; Rasha, a college student whose entire family is jailed on immigration charges; Yasmin, a high school student who wants to serve on the student council, but faces challenges because of her religion; and Akram, a Palestinian-American who wants to leave the country in which his father worked so hard to build a life.

Bayoumi, whose work has appeared in the Nation and the London Review of Books and who co-edited "The Edward Said Reader," spoke to Salon by phone.

What do you mean when you say young Arabs and Muslims are the new "problem" in American society?

Everybody has an opinion about what it means to be an Arab or a Muslim. Young Arabs and Muslims are the ones most feared by the culture at large, so it was very important for me to excavate the stories I found to illustrate the realities and tempos of real life during the age of terror.

In the wake of Sept. 11, thousands of Arabs, Muslims and South Asians were arrested and detained for weeks or months on immigration charges. You open the book with the story of Rasha, a 19-year-old college student whose family was rounded up in a raid. What happened to her?

Rasha has lived in the United States for almost the entirety of her life, even though she was born in Syria. She came as a youngster after her family was granted a tourist visa. Her family applied for asylum status after leaving behind a very brutal regime in Syria. Asylum claims take a very, very -- almost inhumanely -- long time to adjudicate, so they lived in this kind of in-between zone where many people live. They're not quite legal. They're not quite illegal. This made them very vulnerable, as it made a lot of people vulnerable after Sept. 11.

She was one of thousands of people that were rounded up in these mass arrests in the months after Sept. 11 precisely because of the vulnerability of her immigration status. She also suspects her family was reported to the government by a snitch in the community. Regardless, she spent three months of her life in prison, which she felt was a great injustice. She thought she would never be in prison unless she had done something wrong here.

Her entire family was rounded up in the middle of the night.

They were woken up in the middle of the night. The street was blocked off. They were put in shackles, especially her brother, who spoke back to one of the officials. The official then said to him something to the effect of "Put your hands together, like when you pray." The whole family was really traumatized by the horror of the whole ordeal. It lasted several months and involved several different prison institutions. She got an education in what the prison system means. Immigration and criminal detainees are often held in the same place. Her mother was incarcerated with her, as was her sister. The two daughters were trying to make this ordeal as easy as possible on their mother. She's really come through it as a much stronger person. [Rasha's family was eventually released from prison, but the immigration case against them is still pending].

There is an interesting dynamic at work with one of your other subjects, Akram. His father is a Palestinian who immigrated to America and built a life with a mom-and-pop grocery store in Brooklyn. Akram, on the other hand, is disenchanted with America's treatment of Muslims and wants to move to Dubai to teach English. Is this part of a wider trend?

Yes. Akram's story is not exceptional. The Gulf as a whole and Dubai in particular have an allure to this younger generation for many complicated reasons. One of which is there seems to be a growing hostility to all things Muslim in the United States. They think if they go to the Gulf they can escape a lot of that. Then there's the role of globalization. Dubai is now seen as a hot spot -- it's where the action is. It's interesting to me because this earlier generation, his father's generation, believed that about the United States. They could come to the United States and fulfill all of their potential. Now, in a lot of ways, their children feel that way about a place like Dubai.

Despite all the coverage of Muslims and Arabs after Sept. 11, you write they remain "curiously unknown" to many of their neighbors. Why does this ignorance persist?

I think a lot of the coverage seems to be driven by reporters looking for a particular answer. If you want to find the exceptional immigrant who's going to prove to you how easy it is to live in the United States even as an Arab or Muslim, you will find him. If you want to get the hothead who says something that's extreme, or is interpreted as extreme, that's not a problem either. I was really looking for how people were actually living their lives. A lot of non-Arab and Muslim Americans are surprised at the range of religiosity, for example, within the community. Most people think that all Muslims are very religious -- and that's just not the case.

Through connections you made reporting this book, you were able to sit in on a revealing closed-door meeting between the Muslim community in Brooklyn and the FBI. The meeting, as you describe it, is surreal: The FBI agents demand community members condemn terrorism in front of them. The agents also say they are there "to instill a sense of love for our precious freedoms." The FBI's attitude toward the community seems the opposite of how you would go about forging a productive relationship. Overall, how successfully have law enforcement officials engaged the Muslim community after Sept. 11?

I don't think they've done a good job of building bridges and reaching out to the community. There have been probably hundreds if not thousands of meetings, between different communities in the United States and law enforcement officials. It's almost become a sort of routine thing where the law enforcement officials will speak a few words of Arabic. They learn a couple of facts about Islam. The community leaders speak. They have a nice meeting, but nothing really changes as far as I can see.

One of your other subjects, Sami, a Christian whose mother is Egyptian and father Palestinian, is a Marine who fights in the Iraq war. Shortly before shipping out, he makes an appointment with his commanding officers. "I have a conflict of interest," he says. "I'm Arab, and I can't fight against my own people."

He was on an overnight bus down to his basic training when Sept. 11 happened. All the soldiers knew that this was not what they had signed up for. They would have to face actual military conflict. That meant for him -- and I'm sure a whole lot of people -- that they had to find a lot of courage where they may not have looked before. He tried to find ways initially to not go to war, even though he never had a very strong allegiance to his Arab identity prior to shipping off to Iraq. While he was there, he starts to engage the translators who are there -- some of the locals, but mainly people from stateside who are translating for the military. These deep links of kinship are awakened in him. Sami has a complicated story to tell about his relationship to war and to identity and his own Arab-ness.

Is there a thread that connects each of these stories?

All of these people are working out who they are in a difficult time without a hint of self-pity. It's not a maudlin book at all. For the most part, too, they are pretty optimistic about their own futures and, really, the future of the country.

Has the experience of Arabs and Muslims after 9/11 changed the community's approach to politics or spurred more political engagement?

I think there's no question that it has. The community has always been to some degree political. The politics that it had been concerned about prior to Sept. 11 were primarily overseas. After Sept. 11, that was a luxury that could no longer be afforded. Your concerns had to be on the domestic side of things and on foreign policy. You have the growth of certain organizations. They speak in a much more American idiom. They are learning very quickly about making alliances with other groups. I think on the whole the community has been more politicized and, on the whole, it is working toward a more progressive agenda.

Barack Obama is the first presidential candidate with significant ties to the Muslim world. However, the New York Times recently ran an article saying some Muslims feel snubbed by Obama's campaign.

There was a time when Obama really electrified the young Arab and Muslim Americans that I know. They felt really optimistic about him because he seemed to have a really different kind of politics. You could trace that all the way back to the speech he gave at the Democratic Convention in 2004, when he said something to the effect of "If an Arab-American family is rounded up without due process that threatens my civil rights as well." In the Arab and Muslim community, he was seen as someone that could really achieve change, especially after the Bush administration.

But what happened since then is a shift to the center. The sense we could expect a more even-handed policy when it came to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict -- that now seems naive. His stand on withdrawing troops from Iraq seems harder to get a hold on. There are several other things, including the level of symbolic policy. It seems that his campaign feels the idea that people associate him with being a Muslim as a smear.

How do you think Obama should deal with the rumors that he is a Muslim?

He should adopt a "Seinfeld" response -- even though he's not a Muslim, there isn't anything wrong with being a Muslim. Obama is continually running away from it. Actually, he's just come out with something in the last few weeks -- that Muslims are proud members of the human family like everyone else. There should be more of that.

Has there been any silver lining to the experience of Arabs and Muslims over the last six or seven years?

I think that multiculturalism is a much harder project than recognition, tolerance and acknowledgment. Multiculturalism means dealing with a large group of people that have different ideas about different things -- even within different communities. The United States is in some ways grappling with that question, and grappling with it more profoundly in the wake of Sept. 11. It could potentially change not just how things are run in the United States, but how the United States relates to the rest of the world. To me, if the future is going to hold anything, it's got to hold a "we're all in this together" kind of thing. In a way, the best parts of the response to Sept. 11 indicate that as well.

Shares