"I remember the moment I first became aware of aging," says the novelist Kate Christensen, now 46, at a rooftop cafe near her house in Greenpoint, in Brooklyn, N.Y. "I was 30. I looked down at my knees and the skin above them had become a little loose. And I thought, 'And so it begins'!"

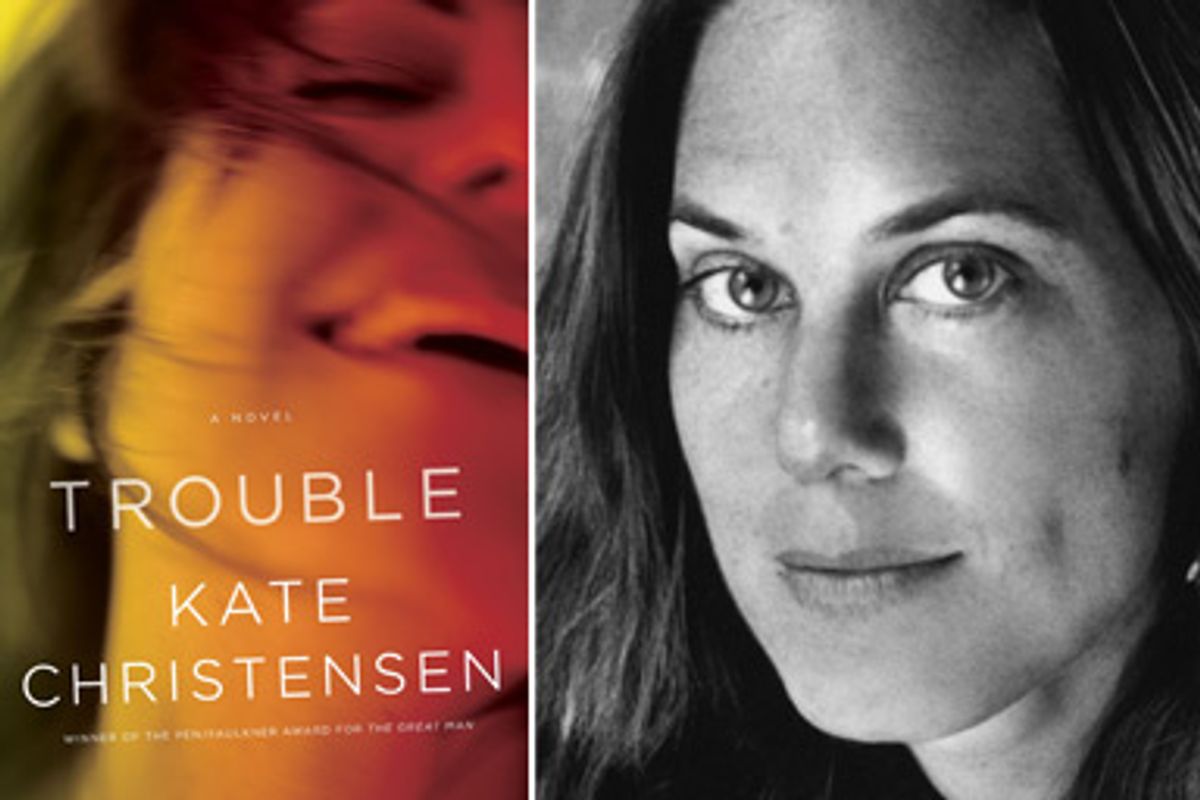

Probably the swiftest way to trivialize the work of a woman writer is to make a big to-do about how sexy she is in person. But Christensen, wearing no make-up and a fitted gray dress, has the easy and direct confidence of a person who feels good in her own skin. Her last novel, "The Great Man" (which won the PEN/Faulkner award), was about three women in their 70s and 80s -- two widows and an embittered lesbian painter -- who rediscover love, lust and ambition after the death of the "great man," an artist who had always towered over them all.

In her latest, novel, "Trouble," two college best friends in their mid-40s, Josie, a Manhattan psychotherapist, and Raquel, an indie rock star, meet up in Mexico City for a "Thelmita and Luisa"-style adventure. Josie has just informed her professor husband, Anthony, and her adopted daughter, Wendy, that she is moving out. Raquel is hiding out from the paparazzi (her most virulent pursuer is a Latina lesbian blogger known as Mina Boriqua) after having been vilified for dating an HBO star half her age, who also happens to have a pregnant girlfriend. The two spend five days in Mexico drinking sangrita and mescal, eating chorizo tacos and chilaquiles, hanging out with artists, and getting reacquainted with a new adult version of their younger selves. But while Josie is coming out of hibernation and reclaiming a sexuality she didn't feel in her 20s, she doesn't realize that Raquel may be going in a very different direction.

"I like being against the prevailing winds," says Christensen. For example, Teddy and Lila, her protagonists in "The Great Man," experiment with casual lesbianism while at Vassar College in the '50s, whereas the three best friends in "Trouble" -- Josie, Raquel and Indrani -- rebel while at a liberal arts college in the Northwest during the '80s by not having sex with each other, not being vegetarian and calling one another "girls" -- much as Christensen did with her own friends at Reed College in the '80s, when political correctness was the thing to do. "Reed was very earnest," says Christensen, "and I felt too ironic to be there. I've never been an outward rebel, but inside I just rebel deeply. And at Reed, I ate bacon."

Over warm tomato soup, she tells me about the secret lives of therapists, the pleasures of sex in one's 40s and why the character who most resembles her in her fiction is a gay man.

In "Trouble," there is a moment of clarity when Josie sees herself in the mirror and decides her marriage is over. Does it happen that quickly, or are we to believe that it's something she's been struggling with for a while?

That whole thing in the mirror -- I see that as a fairy tale moment. It's risky in a first chapter to have a character do something like that when you don't know her yet, and it starts out with this very superficial back-and-forth flirtation with a sleazy English guy, talking about Madonna. The image in the mirror just brought to her attention what she had subconsciously realized at this party and probably had known for some time: I intended it to be a lit match on some tinder that was already dry and ready and stacked up. But I just had this really strong image when I started the book: This is the image with which it must begin. I don't know why. It just came into my head as the catalyst of the novel.

Josie says several times that the sex she's having in her 40s is better than the sex she had in her 20s and imagines that men have always felt like this. Any ideas why it is better?

She experiences sex in her 40s as being about her own desire for a man rather than the thrill of her power over him, his desire for her -- which defined sex in her 20s. She knows what she wants now, isn't afraid to want, and can allow herself the pleasure of desiring a man. Part of this comes from comfort in her own skin, and part of it comes from the fact that this affair isn't about power or marriage-and-babies, it's mutual lust without expectations or pressure.

How funny is it that Josie, a former Catholic schoolgirl, finds sexual liberation in Mexico, a Catholic country?

The fact that she's a Catholic in a Catholic country experiencing a sexual renaissance in what is technically an extramarital affair makes visceral sense to me -- there's the thrill of the sort-of-forbidden, which is always hot, right? She's caught up in passion and sex while her (also Catholic) half-Mexican friend Raquel is spiraling downward in excruciating heartbroken pain in the cruelly public aftermath of an ill-advised affair; their diverging trajectories form the dramatic spine of the plot, but also represent both sides of an interesting coin: the effects of acting on pure desire without much thought of the consequences. One of them gets away with it; the other doesn't.

When Josie and her husband tell their daughter, Wendy, they are getting divorced, she encourages them to go ahead and do it, not "stay together for the children" -- pretty much helping to absolve Josie of any guilt she might have about leaving. Do you think this is typical?

It's hard for me to generalize about kids and divorce. I think every family's experience is different; some kids are devastated by it, others relieved, and so forth, no matter what generation they're from. With Wendy, I was playing against expectation, which was fun for me -- I wanted her to be more grown-up than her mother and more connected to Josie than either of them know. She's been brought up by a mother who's been suppressing her feelings, denying herself pleasure, stuck in a marriage that's not bad, it's just not enough for her. As soon as Josie wakes up, comes unstuck and leaves, Wendy feels a kind of respect for her that's been missing in their relationship -- like, great, Mom's getting a life! She's proud of Josie, almost, for leaving Anthony.

In your first novel, "In the Drink," the protagonist, Claudia, was a young New York woman around the same age you were when you wrote it. Whereas the characters in your last three novels were very obviously different from you: The title character in "Jeremy Thrane" was a gay man, Hugo in "The Epicure's Lament" was a middle-aged misanthrope, and Teddy was in her 70s. Josie, once again, is your current age, 46. She is a therapist on the Upper West Side, and you are a writer in Brooklyn, but it seems the two of you could easily run in similar circles. Was it scary to have a character whom readers might mistake for you?

It was totally scary. She's so not me. Because we're the same age, and because people confuse fact and fiction, inevitably they will think it must be autobiographical, and that Josie must be some version of me. I felt about Josie much the same way I felt about Hugo and Jeremy and Claudia, who also is and is not me: a feeling of identification with them but also a sense of detachment. Jeremy Thrane is the most like me and that is the most autobiographical of all my novels.

And he's the one least likely to ever be confused with you.

Exactly. Because he's a gay man. I find Josie to be kind of annoying sometimes -- annoyingly opaque and clueless and kind of self-involved. I wanted to make her flawed and not heroic. Those are the kind of people I find most interesting. If she's a part of me, it's not my best self. Often I choose characters who express not my best self, but the sides of me I haven't developed or haven't expressed.

There's a great line near the end of the book where someone describes Josie as "perceptive but wrong." That's a pretty interesting thing to say about a woman who makes her living as a therapist -- that is, in large part by her perceptions of others.

It's selective myopia. She sees what she needs to see and what she wants to see, but she is increasingly self-involved as she gets happier and happier. When you're unhappy, you're more compassionate on some level.

And about her being a therapist: I've had a lot of therapy in my life. And my mother's a therapist. So I've had ample opportunity to study the therapist at rest. I've always been fascinated by wondering, "What do they do between appointments? What was she doing right before I walked in? What is her life like?" Well, in Josie's case, maybe she's thinking about some guy she picked up at a bar last night and now she's eating breath mints and burping up wine. My mother has corroborated this: She says whatever is going on in your life, you switch into therapist mode as soon as the person walks in and you have to become a professional. It's like being a writer. For me, no matter what is going on in my personal life, when I sit down to write, I have to switch that part of my brain off.

Josie is able to be incredibly professional when she's with a client, but then when she leaves, she goes to her friend Indrani's to drink rum and has a big fight with one of her best and oldest friends that seems kind of childish, then leaves her husband, then goes down to Mexico where she's "on vacation." That whole window to the clinical, analytical part of her psyche is turned off. It totally makes sense that the shrink would go on vacation and be on vacation. Really, she wants Raquel to be free, because she wants to be free. She thinks Raquel is doing exactly what she's doing: reconnecting with herself. Instead, Raquel becomes more and more self-aware as the novel goes on, while Josie becomes more and more clueless.

And the reader herself becomes clueless, because she's seeing everything through the eyes of Josie. It's an interesting tactic, to show the action through the eyes of one of the more limited narrators.

No one ever uses the term "limited first-person." But that's the voice I'm most comfortable in: The person who has limited self-knowledge. There's a whole lot that the reader sees that she doesn't. The danger in that kind of narrator is that the reader will lose patience with her. I have to see what Josie doesn't see. I have to really be in control of her voice and her perceptions and really show what she is not seeing -- all the subtleties that she's not picking up.

I've found that characters I've based on real people, if I've disguised them physically, people don't recognize themselves. It's hilarious. They just don't. It never occurs to them that I'm writing about them, because they're not blond. They're not 52. They're not rail-thin or overweight.

So people recognize their physical profile, but not their psychological profile?

Absolutely. And when the two go together, they recognize themselves physically and then they see what I'm saying about them. I've offended a couple of people. But I've never had a person recognize him- or herself whose physical description I've altered. I find that fascinating.

Shares