At a time when legal gay marriage is spreading across the country and when "American Idol's" Adam Lambert's coming out on the cover of Rolling Stone elicits not a gasp but a shrug, it's easy to forget just how shameful and bewildering being gay in America can be. Just last week, a reminder of that came in the form of a jaw-dropping video from a Connecticut church that showed an apparent "gay exorcism" -- a preacher grabbing hold of a teenage boy and trying with every ounce of his fearsome, trembling baritone to shock the gay devil out of the kid.

It's a scene that could almost have been lifted from "God Says No," the first novel by James Hannaham, about a closeted black man trying to navigate the opposing forces of his faith and his desire. Protagonist Gary Gray grows up in the hell-and-brimstone black churches of Charleston, S.C., and marries a sweet Samoan woman from his Christian college in central Florida, but that's not enough to keep him from hungry grope-and-pokes in the Waffle House bathroom with anonymous men, followed by prayer on bended knee. As familiar as this setup might seem from a dozen shame-drenched political press conferences, Hannaham shifts the trajectory in an unpredictable story that zigzags from the Atlanta avant garde theater scene to a religious reparative therapy program called Resurrection Ministries, where men like Gary struggle to purge their sinful desires.

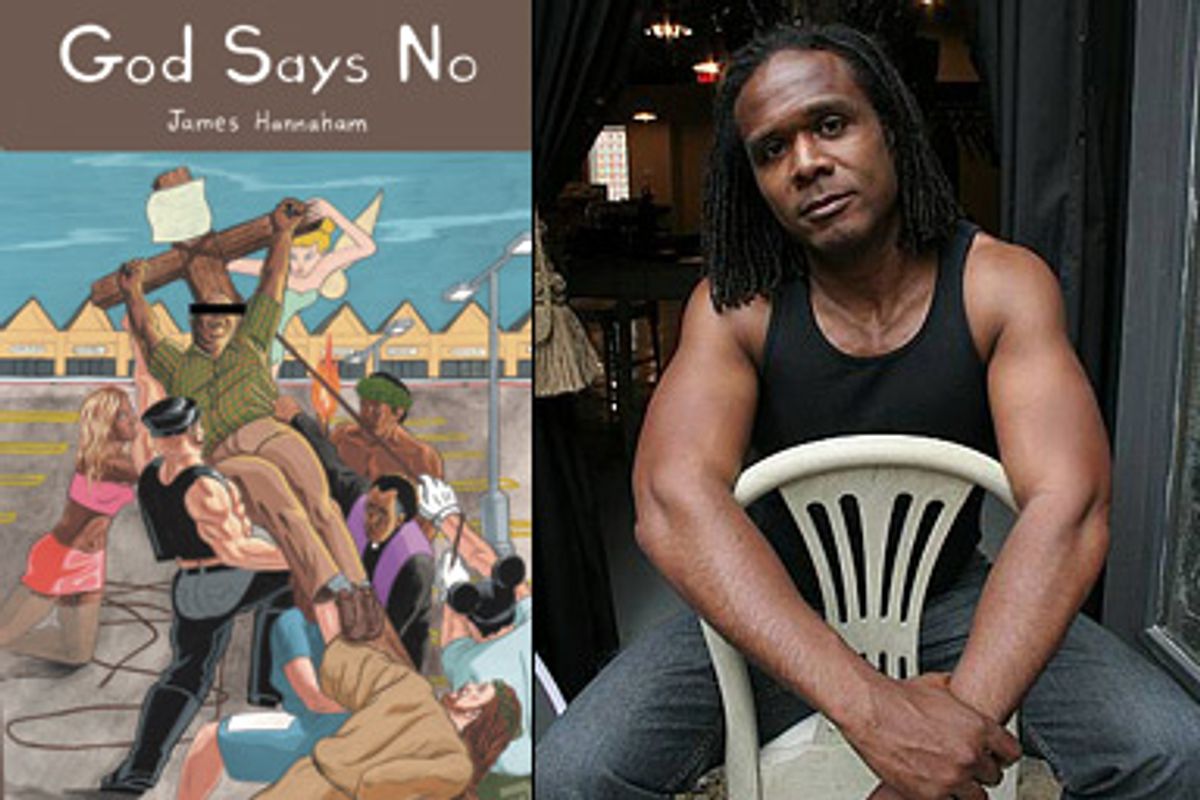

A creative writing teacher at the Pratt Institute, Hannaham is a former staff writer for Salon, where he once penned a piece about infamous men's bathroom dweller Larry Craig. "Most homosexual men spend our formative years in the closet," he wrote, "and once we come out, we tend to deny that closetedness has its pleasures -- and damned juicy ones, truth be told. Having a secret, perhaps double, life gives you a sense of importance, of life as drama." "God Says No" follows as that drama unfolds in original, startling ways. Hannaham was on a tour of the Deep South when we spoke to him about famous political same-sex scandals, outing celebrities and politicians and why Christian programs that try to convert homosexuals aren't entirely evil.

You're a culture writer who lives in godless New York City, and yet you've written this book about a very religious man in central Florida. What was interesting to you about that subject matter?

I was interested in faith -- in particular a faith that falls over into delusion. Although I'm not sure that faith doesn't always fall into delusion. There's so much religion in my background, but I'm a little cut off from it. My mother took me out of church when I was a young boy. But if you go way back in my family there are two things: ministers and teachers. My great-grandfather was an itinerant minister who founded two churches. And I guess there's not that much of a difference between being an itinerant minister and traveling around on your book tour.

Going into the world of someone so deeply closeted -- what did you learn?

I don't want to say I softened about reparative therapy [also known as conversion therapy], but I did realize that it is a place where people who definitely don't want to be gay can talk about being gay, which is something rare for them. They can move away from self-hatred. Maybe I'm romanticizing it. But if you are worried that you might be gay, there are very few places that will even entertain the question, "How do I get rid of this?" Of course, ultimately, I don't think it works.

We live in New York, where reparative therapies are kind of a joke, but I certainly had gay friends in Texas whose mothers suggested it. And they weren't bad mothers at all. Very loving, in fact.

I actually thought the people involved would be a bit more punishing. On the surface it's: We want the best for you, Christ loves you, Christ doesn't agree with this. It's upbeat and friendly. They just have this line that they won't cross as far as compassion goes. It's pretty typical that it's the parents who want the kid to go -- as opposed to the kid himself. The dilemma of gay people worldwide is that we are, for the most part, raised by heterosexual parents who don't understand what homosexuality is. Everyone has to crawl through the tunnel of self-hatred to get where they are.

While you were writing this book, there were several scandals involving closeted religious men: Ted Haggard, Jim McGreevey, Mark Foley, Larry Craig. Were you influenced by their stories?

Strangely, the book was largely in place when those scandals broke. I loved the detail that McGreevey used to overcompensate by going to strip clubs. I wish there was video of that. I was thrilled by their stories, in part because they proved to me that we're not over these issues, and the book would be timely no matter when it came out (so to speak).

A lot of action takes place in men's bathrooms. You wrote a great story for Salon, after the Larry Craig scandal broke, about why bathroom sex is hot.

Are you going to ask if I had sex in a bathroom?

You said in that article that you haven't. Should I believe you?

Yes, I'm too romantic for bathroom sex. There were early experiences where I might have done it. I guess I didn't have the guts -- which is odd to say, because it seems like a cowardly thing to do. You're treating another person as an object. But it takes chutzpah, if not guts.

But what makes it hot?

The big lie about anonymous sex is that it's anonymous. If you meet someone in a bar you're going to see them in the next few weeks. You're going to run into them at a party or something. If it's an encounter in an airport bathroom it's pretty much as anonymous as you can get. It also probably feels like you're doing something really sleazy and naughty-hot. I feel hypocritical explaining the allure having never done it, though I'm fascinated by the psychology of someone who would.

What do you think about movies like Kirby Dick's "Outrage," which outs some conservative politicians, or critics like Michael Musto who have made campaigns out of rattling the celebrity closet?

People who are not out and are hurting the community should be outed. People who are gay and aren't hurting anybody should be left alone. I mean, Rosie O'Donnell -- they hounded her for years to come out and now she did, and how obnoxious is she? Did we really need her as a spokesperson? Do I really want Tom Cruise fighting for my cause? No, thanks. But then you look at someone like Steve Gunderson, a congressman from Wisconsin, who voted anti-gay while he was in the closet and was outed and he's completely changed his position now. He was the only Republican to vote against the Defense of Marriage Act. How anti-gay can you be once everyone knows you're gay?

An important aspect to your central character, Gary, is that he's overweight and not what you'd call good-looking. Why give him those qualities?

Gary's not actually ugly, in my view, but other characters tend to conflate his weight with ugliness. I had weight issues when I was younger. But also, I wanted him to be somebody who was overlooked in any number of ways. Being overweight can make you marginalized in the gay community, which is full of former fat guys who hate fat people out of fear.

I met this guy from South Carolina who said he became fat to avoid dating a girl. Food is also comforting. Food can't reject you. Gary's problem, even more than being gay or fat, is that he can't control his appetites in general. Everything is intense for him, and he doesn't know how to deal with it, so he lives in this place where he 's being told not to value his pleasures and to think of them as pathologies. That's what causes him such deep anguish. And makes him a normal American, ultimately.

Shares