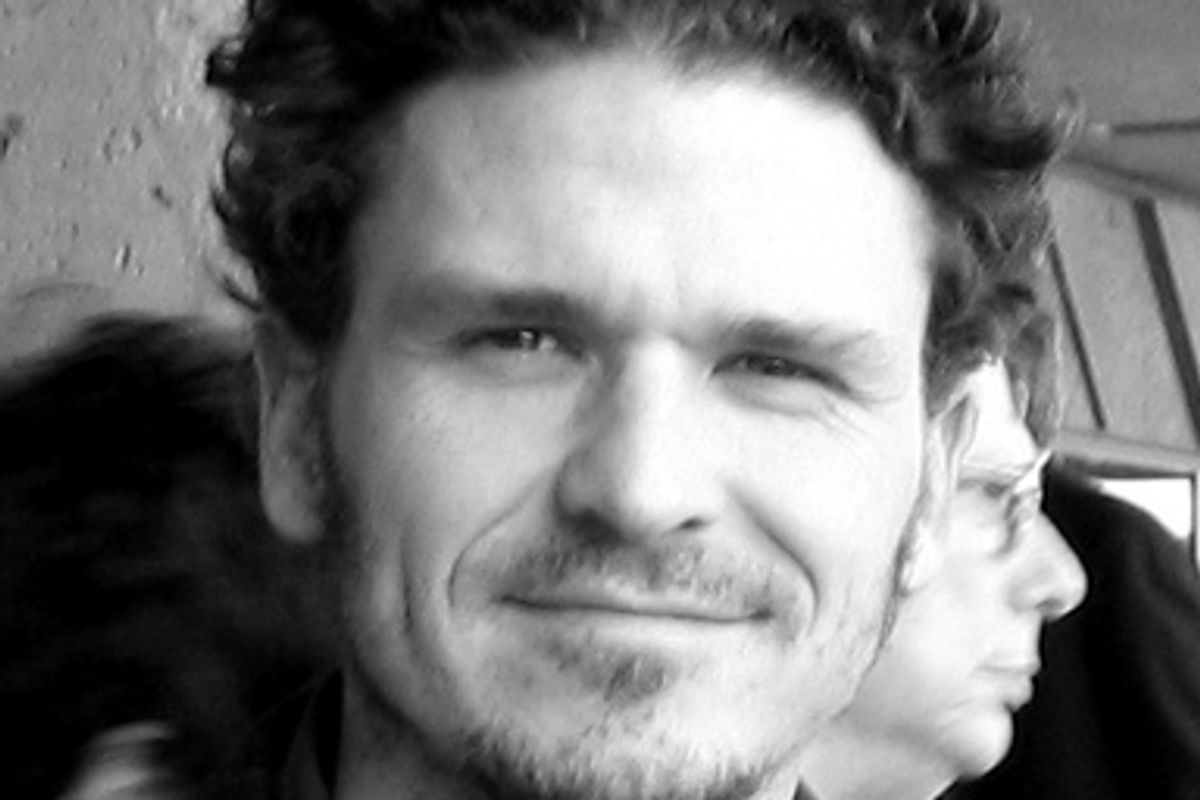

For better or worse, Dave Eggers will always be known as the author of the quasi-fictional memoir "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius," a 2000 bestseller that recounted his experiences raising his little brother after the sudden deaths of their parents. (He began writing it, I should note, while employed as an editor at Salon.) That sudden rise to literary celebrity threatened to turn Eggers into a Generation-X cult figure or avatar of sincerity, but viewed in retrospect he handled the lightning strike of success about as well as anyone could. He has refused to be trapped by the highly self-conscious literary voice of that book and, more impressive still, has tried to turn his success toward real-world ends.

Eggers has founded a magazine and a publishing house, funded a wide range of youth-literacy programs through his 826 Valencia center, and co-directed an oral history program called Voice of Witness, focused on permitting survivors and witnesses of human-rights abuse to tell their stories. Among various other things, Voice of Witness sparked "Zeitoun," Eggers' latest nonfiction volume. You couldn't write a book more different from "Heartbreaking Work" if you tried. Like his 2006 novel "What Is the What," which was based on the life of a Sudanese refugee, this is a work of testimony, and almost of ventriloquism.

Its protagonist is Abdulrahman Zeitoun, a Syrian immigrant turned New Orleans contractor and landlord who stays in the city when the rising waters of Lake Pontchartrain rupture the levees in late August of 2005. Zeitoun finds himself nearly alone in an eerily quiet drowned city, which he patrols for several days in a second-hand canoe. Along with a loose network of other New Orleanians who remained through Katrina, Zeitoun rescues stranded elderly people, feeds abandoned dogs, and grills lamb with friends on the roof of his flooded Victorian in the historic Uptown district.

Although Zeitoun has stayed behind primarily to protect his own property -- while his American-born wife, Kathy, and their four children drive north to stay with relatives in Baton Rouge -- he comes to see his mission in New Orleans as something much larger. While the outside world receives grossly exaggerated reports of anarchy and violence, Zeitoun finds a sense of purpose in a city that is underwater but largely at peace. A devout Muslim, he begins to wonder whether God has chosen him as a servant and witness in this dire emergency.

After a group of heavily armed men and women, wearing uniforms with no identifying badges, burst into a rental property that Zeitoun and his friends are using as a staging area, he has ample time to repent of his sinful pride. He disappears into a quasi-legal bureaucratic nightmare that resembles a Kafka story but is all too real. Kathy does not hear from him for weeks, and given the hysterical news coverage, assumes the worst. Is Zeitoun's life insurance paid up? Can she begin again without him?

"Zeitoun" is a story about the Bush administration's two most egregious policy disasters -- the War on Terror and the response to Hurricane Katrina -- as they collide with each other and come crashing down on one family. Eggers tells the story entirely from the perspective of Abdulrahman and Kathy Zeitoun, although he says he has vigorously double-checked the facts and removed any inaccuracies from their accounts. At first, as a reader, I felt some resistance to this tactic -- could the Zeitouns possibly be as wholesome and all-American as Eggers depicts them? -- but the sheer momentum, emotional force and imagistic power of the narrative finally sweep such objections away.

In many ways, "Zeitoun" is an old-fashioned journalistic yarn, an oral history rendered in literary form that seeks both to inspire and outrage its readers. Entirely free of authorial asides, its innovative quality lies in its thoroughgoing rejection of the "me journalism" that has dominated reporting for three decades or more. Eggers presents it as a collaboration between him and the Zeitouns, similar in method to his collaboration with Valentino Achak Deng on "What Is the What." (That book was presented as a novel, Eggers says, because it contained numerous reconstructed scenes from many years earlier, whereas "Zeitoun" is strictly nonfiction.)

I knew Dave Eggers many years ago (although not especially well) when we both worked at SF Weekly in San Francisco. I remember him as a quiet and serious young man who was evidently smart and ambitious, and who had some strange domestic situation involving his little brother. (I didn't know the details.) It's safe to say that a lot has changed in his life since then. Among his upcoming projects is a prototype daily newspaper (discussed briefly below) and an all-ages "novelization," to use his word, of Maurice Sendak's "Where the Wild Things Are," to be published this fall alongside the release of Spike Jonze's movie version, which Eggers scripted. He called me the other day from the San Francisco office of McSweeney's, his publishing imprint.

I notice that you've been inviting people to appeal to you for a pep talk on the future of the printed word, which we're all very worried about. So if I were to write to you and say, "Dave, cheer me up about the future of writing," what would you say?

Salon still exists, thank God. I think there's a future where the Web and print coexist and they each do things uniquely and complement each other, and we have what could be the ultimate and best-yet array of journalistic venues. I think right now everyone's assuming it's a zero-sum situation, and I just don't see it that way.

Our students at 826 Valencia still have a newspaper class, where we print an actual newspaper, and we do magazine classes and anthologies where they're all printed on paper. That's the main way we get them motivated, that they know it's going to be in print. It's much harder for us to motivate the students when they think it's only going to be on the Web.

The vast majority of students we work with read newspapers and books, more so than I did at their age. And I don't see that dropping off. If anything the lack of faith comes from people our age, where we just assume that it's dead or dying. I think we've given up a little too soon. We [i.e., McSweeney's] have been working every day on a prototype for a new newspaper, and a lot of what we're doing is resurrecting old things, like things from the last century that newspapers used to do, in terms of really using the full luxury of the broadsheet newspaper, with full color and all that space.

I think newspapers shouldn't try to compete directly with the Web, and should do what they can do better, which may be long-form journalism and using photos and art, and making connections with large-form graphics and really enhancing the tactile experience of paper. You know, including a full-color comic section, for example, which of course was standard in newspapers years ago, when you'd have a full broadsheet Winsor McCay comic. So we'll have a big, full-color comic section, and we're also trying to emphasize what younger readers are looking for, what directly appeals to them. It's hard to find papers these days that really do anything to appeal to anyone under 18, and the paper used to do that all the time. I think there will always be -- if not the same audience and not as wide an audience -- a dedicated audience that can keep print journalism alive.

Turning to your new book, talk about what drew you to the story of Abdulrahman Zeitoun and his family? Didn't they come to you through the Voice of Witness program?

That's right. The idea of Voice of Witness is to let survivors and witnesses of human-rights abuses tell their story at length. It started with a course that I co-taught at U.C. Berkeley journalism school back in 2003. The first book that came out of it was "Surviving Justice," which was about exonerated prisoners in the United States. Right when we were publishing "Surviving Justice," Katrina hit.

So we contacted a network of people living near New Orleans, in Houston and Baton Rouge and other cities where New Orleanians had gone, and put "Voices From the Storm" together. That book was 13 or so narrators telling their stories and woven into a day-by-day narrative. One of the narrators was Zeitoun. I was immediately struck by his story, and the next time I was in New Orleans I met up with him and Kathy. I started talking to him to find out what he might not have been able to tell in that five- or six-page section, and it was clear there was a lot more there. Slowly, over the next six months, we began exploring whether there was a way to tell his story in book form, going back to Syria and exploring his life as an immigrant and a New Orleanian.

It's interesting, and in some ways challenging, that you tell the story entirely from the Zeitoun family's point of view. There's none of the pretense of authorial objectivity or neutrality that conventionally goes with journalism. You're not issuing opinions or analysis from on high.

That's true. But that's not to say that it's not factual. If they misremembered something, we corrected it. If they said something that was provably and demonstrably incorrect, we didn't print it. But it's third-person quotes, very much through their eyes as opposed to my take on things, where I come down and give my perspective on their story and the storm and its aftermath. I didn't feel like I had a place in this narrative, other than to help structure the story and make it compelling and readable. It's an effort to disappear into the narrative, which I was also trying to do with my earlier book, "What Is the What." In both cases, I felt like I was most useful being out of the picture.

Which is certainly interesting considering that your first book, the one for which you are still best known, is an autobiographical, self- aware and even self-referential work. Was it important to you as a writer not to repeat that?

Yeah, I think so. After that first book, I wrote some stories that had protagonists that were close to my sensibility or my background. And then I just, to some extent, got that out of my system and wanted to do something new. Not that I would rule out writing in the first person in the future, but I started out as a journalist and that's what my training and degree was in. I missed it for those years. Fiction was actually new to me. This is just a return to the basic training that I had, where one tries to use whatever skills one has to facilitate the telling of a story that you find important and that you might be able to bring to a wider audience.

This is even closer to journalism than "What Is the What," right? That was about a real person but was classified as fiction, whereas "Zeitoun" is nonfiction.

They were very similar processes, actually. "What Is the What" is incredibly close to Valentino's life story and all of the major milestones in his life take place the way that they're described, but it was necessary to reconstruct dialogue and paint scenes that took place 15 years ago. If we were restricted to nonfiction we couldn't, you know, prove what the weather was like on a given day. In this case, because it was so recent we really could prove everything and the memory was so fresh that we were able to call it nonfiction. Otherwise, the processes -- in terms of working in close collaboration, working with their memories and their subjective point of view -- all those things were very similar.

It's worth mentioning that in both cases you're deflecting your author's royalties to some combination of third-party nonprofits and charities, right?

Yeah. I just felt funny, in both cases, benefiting materially from it. I have friends who work in nonprofits down in New Orleans and there's a lot of need there still. More than ever, really, because we're at the stage where some of the work that they're doing and the city in general is getting kind of forgotten. So we thought that if something good can come out of what the Zeitouns went through, then maybe it had some purpose. That was really the main motivating factor, I think, for the family to go into it and to cooperate, as painful as some of these things were to delve back into. Certainly we did go deeper than one's daily memory could go and the kind of version you tell yourself.

I can see why your writer's radar got lit up by this story -- the combination of Hurricane Katrina, the post-9/11 era and a Muslim family. It's kind of an amazing microcosm of the 21st century in America, isn't it?

Yeah, no kidding. You know, there's a new graphic novel called "A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge" by Josh Neufeld, and one of his protagonists is also Muslim-American. Their story, like that of the Vietnamese-American community in New Orleans, was a lot less told. And it's a legacy of the war on terror, this mentality that an overwhelming military response was the solution to a humanitarian crisis. It just felt like a real manifestation of the Bush years. FEMA was folded into Homeland Security and that became a disaster. And then, because of the military response and the perception that law and order was the first order of business, you had the suspension of pretty much all rights. Martial law was more or less enacted in New Orleans, and then you have one man who is just caught between all these lines, all these lumbering forces.

Zeitoun was among thousands of people who were doing "Katrina time" after the storm. There was a complete suspension of all legal processes and there were no hearings, no courts for months and months and not enough folks in the judicial system really seemed all that concerned about it. Some human-rights activists and some attorneys, but otherwise it seemed to be the cost of doing business. It really could have only happened at that time; 2005 was just the exact meeting place of the Bush-era philosophy towards law enforcement and incarceration, their philosophy toward habeas corpus and their neglect and indifference to the plight of New Orleanians.

It's a completely horrifying story, and I felt like my jaw was on the floor the whole time once I realized where it was going. But Zeitoun actually got out relatively quickly compared to some people, right?

There were hundreds of people that did months in jail, and I'm sure there are dozens of cases of prisoners who did over a year in various jails and prisons around Louisiana, where no one even knew where they were. It's unprecedented in American history, I think, this wide a suspension of habeas corpus. I don't think we've seen that since the Civil War.

I wonder whether the most damaging long-term consequence of the Bush administration is that by and large Americans are ready to accept things like this, which would have seemed like science fiction 10 or 15 years ago.

I think there was a dark age, right in the middle there, from 2003 to 2006 especially, when anything seemed possible and nothing was surprising. Kathy felt so relieved when she found out that Zeitoun was in prison, like, "Well, I know where he's at and he's safe and he's alive." But for his family in Jableh, Syria, and his brother in Spain, that was even more worrying. That their brother, a Muslim from Syria, was in an American prison. It was really brought home when I met his family there and learned that they were gathered around the TV and phone for weeks, worried about what might happen to him in an American prison. I don't think anyone in the Middle East would have normally thought, before 9/11 and before Bush, that that was the worst situation somebody could be in.

One of the ingenious things about the way you tell the story, from Zeitoun and Kathy's perspective, is that it outflanks the reader's preconceptions, or maybe even your preconceptions, about what a Syrian immigrant and his Muslim wife would be like. You don't have to come in as an author and say, "Hey, listen! They're normal people, they watch TV." You're just presenting their lives and we ride with them.

Yeah, that was one of the goals. The first time I met them I was just in their living room and Kathy had just bought a big-screen TV on sale from Sam's Club, and the kids were all over the place and their pets were running around. They had chickens at the time. They might even have been watching "Pride and Prejudice." They were just so incredibly all-American in so many ways. And just such a warm and a funny family, where there's all the family chaos that you want. From the beginning, the idea was to de-exoticize the Muslim-American experience and cover the commonalities.

Kathy and Abdulrahman have a really fantastic marriage and a fantastic family, and I wanted to get that across in a seamless way, so that their plight becomes the plight that anyone might have gone through. Certainly it wasn't all Muslims who were caught up in the aftermath of Katrina, so in a way it is everyone's story.

If there is any silver lining to their story it seems like Zeitoun's ancestry and ethnicity played only a minor role in the way he was treated. There's a really crazy period where the guards are telling him "You're al-Qaida, you're Taliban." But it doesn't last that long.

I interviewed two of the police officers that arrested him, and I put it to them: Did his accent or his name have anything to do with it? And they very convincingly denied it. They might not have even heard him speak. Gross indifference and incompetence played as much a part as ad hominem suspicion and incarceration with intent. So much of this is just systemic dysfunction.

The contrast between the first part of the book, when all kinds of random people in New Orleans are trying to help each other through this painful and destructive experience, and the second part, when the world of authority comes down on them like a ton of bricks, is just amazing. It seems like, if the cops and military had simply stayed out of New Orleans altogether, everything would have been much better than it was.

You know, I've heard that thesis before, and it's fascinating. Zeitoun's friend Todd Gambino counts his rescues at about 200 -- the number of people he plucked off of rooftops and porches and second-story windows and then brought to safety. There were all these incredibly heroic citizens and good Samaritans going around helping. But there were so many police and Coast Guard and National Guard who did phenomenal work too. It's just that overall, as a result of all the misinformation spread by the media, those going in really expected a war zone. All these National Guardsmen, some of whom came from Afghanistan and Iraq and had been trained in house-to-house searches, came in and they were all hyped up, expecting the worst. There was this sense that martial law is in place. We're going to clear out this city at all costs and we're going to cast the net pretty widely. So they came down with unnecessary force. Coupled with a non-functioning judicial system, that produced some mind-boggling human rights violations.

You know, on the failure of the media and public officials to paint an accurate portrait, that still has not been addressed. Having written a couple of times about the film "Trouble the Water," I can attest to the fact that there are a lot of people out there, among Salon's readers, who still believe that there really was rape and pillage in New Orleans, that armed men were shooting at helicopters and all that stuff.

Yeah, there are those that think that it's some sort of liberal or left-wing apologist baloney to say otherwise. But all the statistics bear out that crime was grossly exaggerated. They predicted hundreds of bodies in the Convention Center and the Superdome, and they found only one murder among both. More than any other event in recent history, this exposed the quiet racism that's right there under the surface, these assumptions.

Everyone's willingness to accept the idea that a city would turn into this chaotic war zone in the aftermath of a storm, it really necessitates a long soul-searching for everybody that bought into that. Zeitoun's relatives believed it too, and thought that the major danger he faced was being preyed upon by these lawless gangs of young men. And that's the twist in the book, that I'm hoping people don't see coming. But maybe I'm already giving it all away. [Laughs.]

Shares