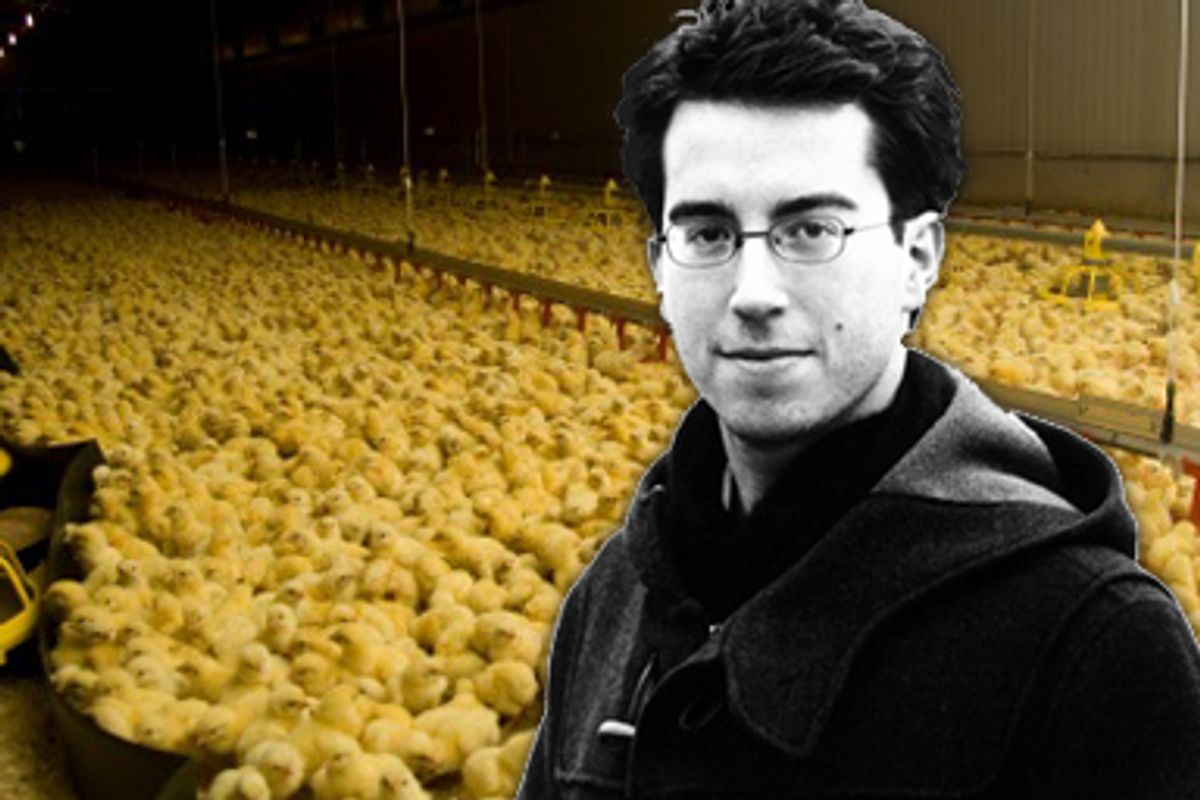

Jonathan Safran Foer is a strict vegetarian, but his most recent book, "Eating Animals," is not a screed against meat. It is, rather, an indictment of the corrupt, large-scale factory farming that dominates the American meat market. A journalistic work with a novelistic feel, the book is the result of three years investigating the U.S. meat industry, and it weaves together animal activist and farmer interviews with statistical research and even memoir to provide a sweeping account of Big Beef and its social, economical and environmental impact. Descriptions of animals suffering on the "kill floor" are enough to incite squirms from even non-animal lovers, but cruelty is not Foer's only grievance: There are health concerns and devastating environmental damage at issue as well.

"Eating Animals" may be Foer's first big swing at nonfiction, but primary themes hearken back to Foer's two critically polarizing novels, "Everything Is Illuminated" and "Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close." Family folklore and ideas about the complexity of memory permeate each; "Eating Animals" begins with a section titled "Storytelling," about Foer's grandmother, a Holocaust survivor (and passionate carnivore). "The story of her relationship with food," he writes, "holds all of the other stories that could be told about her."

The book is not without controversy, of course. Food politics gets at the very heart of what it means to be American -- alas, human -- and the subject of how and if we eat meat stirs up intense feeling. Last week, Natalie Portman kicked up a tiny tempest when she wrote about "Eating Animals" in a column on Huffington Post, championing Foer's argument but adding her own painfully tone-deaf riff about rape. (The controversy took place after the Salon interview but when I reached him afterward via e-mail, Foer had this to say about Portman's column: "It was such a thoughtful and generous piece of writing. I felt gratefulness more than anything else.")

I met with Foer recently in a coffee shop near his home in Park Slope, Brooklyn, where he spoke about what's wrong with PETA, how he finally went so local he ditched Amazon -- and what Americans can do to help put an end to the evils of factory farms.

This is not a straightforward case for vegetarianism. What is this book making a case for?

It's an explanation of my own vegetarianism, and it's a straightforward case for caring and thinking, and for the ideas that matter. These little daily choices that we're so used to thinking are irrelevant are the most important thing we do all day long. An enormous and very destructive force -- historically, it's unprecedented how destructive our farm system is -- has taken over America and is starting to take over the world. And unlike so many other horrible systems, this one doesn't require electing a new government or raising billions of dollars or fighting a war. It can be dismantled just by people making different choices. I think there are a lot of different choices people can make that will lead to dismantling the system. It's not like everybody has to go vegetarian. There are plenty of people who feel like, for whatever reason, they just can't stop eating meat, but if they bought meat at the green market, from farmers they know by name, that's as effective a rebuttal.

What if you live in a city and you don't live near a farm? I'm sure there are tons of people like that in New York. What's your suggestion for them?

Well, in New York everybody is near a green market. Everybody is near a source of family-farmed meat. In fact, cities are frankly the best place to be in terms of that. But you ask a good question because there are a lot of times when you don't have a choice. Like, in a restaurant, you never have a choice, with the exception of -- maybe there's 10 restaurants in New York City. In restaurants people are often faced with this problem, like, "Well, I'm either going to have to leave my values at the door and just eat this stuff, or eat vegetarian." Those are the only two choices we have. And then people think, what does it mean to care about something if you don't act on that care? Even if it makes things less convenient, even if it makes your meal less enjoyable -- which is totally possible. But we make decisions all the time guided by our values that make our lives less convenient and less enjoyable. We do them because they're things that matter more to us than a momentary pleasure, momentary comfort. I don't know why food would be an exception.

How has writing and researching this book changed the way you and your family eat?

We were vegetarians before, and we continue to be, and we're raising our kids vegetarian. One thing that has interested me about my response to this whole project is that it's made me care about other things. I mean, caring is contagious. It's very hard to care about one thing and not care about its neighbor. For example, I was not a huge advocate of buying things locally, not food but like books -- anything. I would buy books on Amazon all the time. But for whatever reason, the subject does not have anything to do with that, but the process of writing it made me much more concerned about buying things locally, supporting my neighborhood stores, it mattering that I know the person who's selling me something. That's something that's great about food is that so much intersects there. Tolstoy famously said, "If there were no more slaughterhouses there would be no more battlefields." I don't think that's true, and I don't think all battlefields are bad, but what is true is that when you start to care about food and think about the animals and how we raise them, it encourages you to have lots of other thoughts.

This is your first nonfiction book.

Well, it's my first and my last. I don't think I'll ever do it again. It's not something that interests me. I felt a little bit like dressing up for Halloween. Although, my interests at the end of the day were never really journalistic and it always did feel personal. And the themes that this book falls back on are the themes that my novels fall back on, like, how are lessons transmitted through generations and families, how do our decisions matter, how do they influence others? So, part of what inspired me to write about this was not that I cared about it so much but that nobody was writing about it. There are a lot of things I care about, but great people are writing about them. And there hasn't really been a mainstream book about meat, despite the fact that it's everything. I mean, if it isn't the biggest, most important issue in our country right now, it's up there.

Did any specific authors or works influence your book?

Many. Of course, Michael Pollan, Eric Schlosser, Peter Singer. I mean if any of them had written the thing that I wanted to read, I wouldn't have had to write my book. See, Pollan is wonderful, but he doesn't really get into meat too deeply; he sort of goes up to the edge of it and then stops. The same with Schlosser. Peter Singer writes about meat very directly, but in a way that I feel doesn't include enough of the messiness of being a person in the world and having cravings, having personal history, having family. Reason has something to do with our food decisions, but not a lot. Most food decisions are made out of emotions or psychology or impulse, and so I wanted a book that included those things.

What were some of the most surprising or disturbing things you found in your research?

The most disturbing thing is not any instance, but the rule. It's a shame in a way that PETA videos or slaughterhouse videos are most people's exposure to factory farming because it gives the impression that the horrible things are the exception, when in fact they're the rule. So an animal running and getting beaten up or running around with its neck slit open: That is the exception, even on the worst farms it's still the exception. But the rule that happens even on the best factory farms is animals are genetically modified to the point of being unable to reproduce sexually, animals that never see the sun and never touch the earth, animals whose cages are never cleaned. These things are not as shocking and don't work as well in a video, but they're something to be concerned with much more because they're happening to billions and billions of animals every year. It's the way that the notion that an animal is a thing has been systematized and it's part of the business model and that everyone thinks this way. That was the most surprising thing.

You also talk about your dog George, and consider why people will eat farm animals but not dogs. Can you elaborate on that?

The book in the beginning sort of presents two approaches. One is philosophical -- is it right or isn't it right? Why do we do this at all? And the other is practical. I side with the practical. I mean, the book moves in the direction of the practical because in a way the philosophical questions are irrelevant. "Is it right to eat an animal, is it not right to eat an animal?" That's how most people talk about vegetarianism. But to me it doesn't even matter. The truth is I actually don't know what I think about that question. What I know is that it's wrong to do it the way that we're doing it. And we could sit here and argue about a perfect farm where animals are treated perfectly and slaughtered perfectly and whether that's right. But if it exists at all it exists in a place that is impossible for us to find on any regular basis. So what we should be talking about is how upward of 99 percent of animals are raised and what it does to them, what it does to the environment, what it does to rural communities, what it does to farmers. And that's bad; I mean, those things are bad. And that conversation preempts the philosophical conversation.

Your grandmother was a huge influence on your concept of food, and you also say she's an unapologetic meat eater. How did she react to the book?

I don't think she's read it yet. I think she will agree with a lot of what I said. I don't think she's going to change. I think she's past changing. But I've had pretty frank conversations with her about what's right and what's wrong, and she'll agree -- as will everybody, by the way. There's not a reader of this interview who will say it's right to make animals suffer unnecessarily. So then it becomes a question of what is suffering to different people and what is necessary to different people. And people can have all kinds of different, very respectable differences of opinion on this question, but I've spoken to my grandmother about why this might be wrong and she doesn't disagree. It's sad. She said in a very upfront way, "I don't think about it, I'm not going to think about it." For someone like my grandmother -- frankly, for a lot of people -- I don't really push it. I think for people who are still forming their habits, like high school students or college students, that kind of willed ignorance is lame at best and something much worse because they're most able to change. They're the ones who are ultimately going to have to foot the bill of factory farming and are more required to do the uncomfortable thinking that a 90-year-old doesn't.

Can you talk a little bit about America's obsession with food?

There's never been a culture that wasn't obsessed with food. The sort of sad thing is that our obsession is no longer with food, but with the price of food. Factory farming supplies a demand for cheap meat. That's it. It doesn't taste good, it's not healthy for us. The only good thing about it is that it's cheap. But the thing is that it's not cheap. It's cheap at the cash register, and it's sold as cheap -- that's the defense for factory farming, "Look, we're making affordable food for normal people and all other arguments are elitist." But in fact factory farming is like the ultimate elitism because it's the most expensive food ever produced in the history of mankind. We pay very little at the cash register, but we pay and our kids are going to pay for the environmental toll, obviously the animals are paying, rural communities are paying. And for what? So that corporations can prosper. The huge agribusiness -- companies make hundreds of millions and sometimes billions of dollars, not in the name of feeding the world, but in the name of making something that's so cheap that people become literally addicted to it.

Aside from getting green meat and eating locally, what are things that both vegetarians and meat eaters can do to help the transition from factory farms to something better?

First of all, they just have to say no to factory farms always. Not sometimes, not most of the time, but always, which means eating vegetarian a lot of the time. I think this issue is frankly more important than our conversation about the environment, because it is the No. 1 cause of global warning. The World Watch just released a report that showed that they thought animal agriculture was responsible for 18 percent of greenhouse gases, but it turns out it's 51 percent. So to talk about the environment and not talk about this is not to talk about the environment. This conversation has to be totally mainstreamed. There has to be a consensus behind it that factory farming is bad and we're not going to support it and we're done with it. And it has to be unacceptable either to pretend these problems don't exist or not to actively engage with them. I'm not saying everybody has to reach the same conclusions, but they do have to agree on the common enemy.

Shares