It's news that should shock and delight dog owners, scolded for decades by trainers and dog whisperers that they must relentlessly assert their dominance over their dogs: Yes, it's perfectly acceptable to let Fido sleep in your bed.

You can also let him enter a room before you, and you can let him win at a game of tug of war, all without fearing that you will somehow signal that you are the submissive one and he is in charge. Contrary to long-cherished theories, dogs aren't competing with us for position in the pack, but are largely performing for our approval. And that -- no matter what the Cesar Millans of the world would have you believe -- is because much of what we've been led to be believe about dogs' hard-wired behavior has been totally wrong.

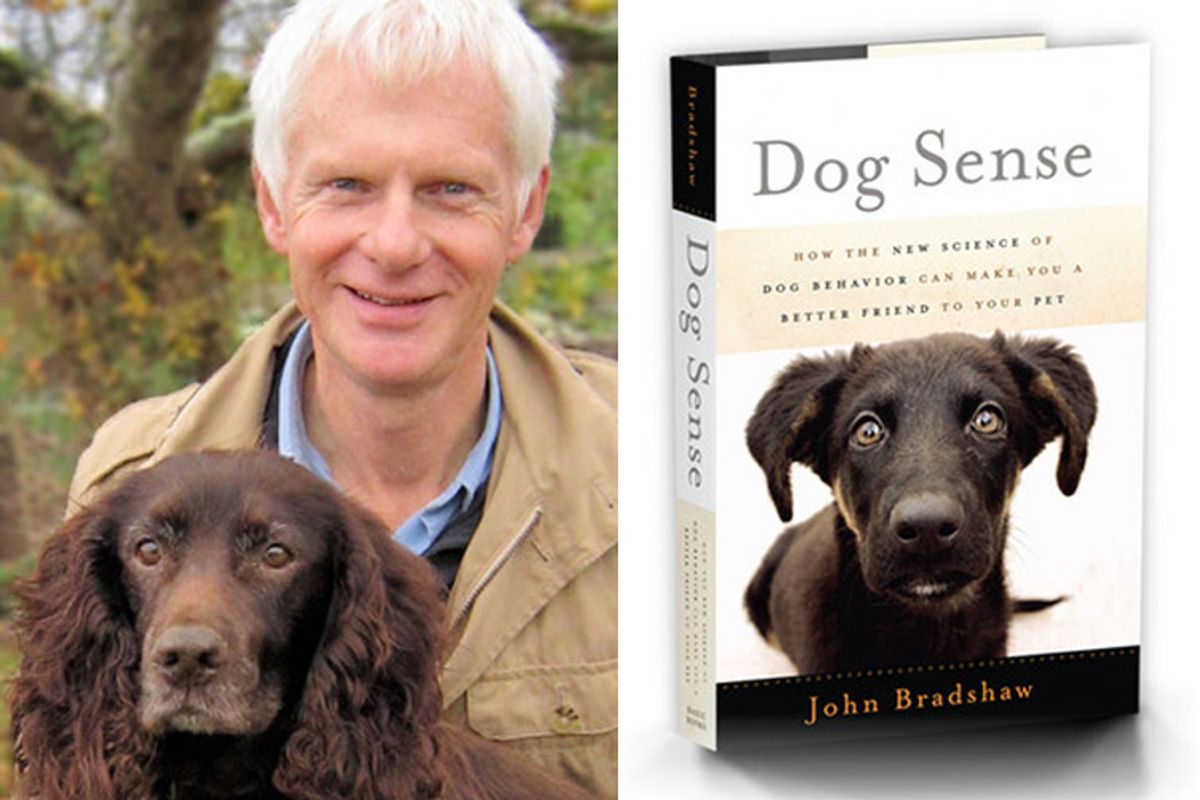

In his densely illuminating new book, "Dog Sense: How the New Science of Dog Behavior Can Make You a Better Friend to Your Pet," John Bradshaw explains how our understanding has been skewed by deeply flawed research, and exploited by a sensationalized media. In place of the rigid, often violent, alpha-led wolf societies we once believed produced the modern dog were actually cooperative, familial groups. And in place of the choke-chain school of negative reinforcement should be a training program based primarily on the positive.

Bradshaw, the Waltham director of the Anthrozoology Institute at the University of Bristol, articulates a revolutionary change in thinking in "Dog Sense" that should liberate both dog and owner from what had so often been portrayed as an adversarial relationship. He spoke with Salon recently by phone.

What's the biggest misconception we have about dogs?

I think the biggest misconception is that dogs are basically wolves that have put on cute little furry coats but are kind of wild animals underneath. And I think that all the science that's been done over the last 10 years really shows that to be a myth. The only bit of it that's true is that the DNA is identical, to all intents and purposes [to wolves]. But DNA doesn't, except very indirectly, code for behavior. And the way that dogs grow up, the way they learn about the world, is completely different from the way that wolves do. That change, brought about by domestication, means that they are very easy to integrate into our world in a way that wolves are not.

But it's fascinating to learn that the influential studies about wolves -- which have so heavily influenced how we treat dogs -- were seriously flawed.

In the earliest studies of wolves, going right back to the late 19th century, they put wolves together in zoos. I think, for its time, the science was perfectly valid, but they did construct these wolf packs assuming that wolves you put together in a zoo would form a society which was typical of wolves. And then it emerged -- really, didn't emerge until the 1990s, when it became possible to really keep an eye on wild wolf packs with developments like GPS -- that families should behave completely differently to groups of animals that are not family.

It's basically the conception, now, that the wolf is an animal that breeds [a lot like] many other social species, birds and all sorts of things, not just mammals. The young, when they grow up, have essentially two choices. One is to stay and help their parents raise the next generation, the next litter. The other one is to leave. Staying behind is genetically very good because they share genes with their parents. When those conditions are good, it's a sensible strategy to stay around for a couple of years. Help your parents, learn a bit more, and then go off on your own. And that's essentially the way that the wolf biologists now conceive wolf societies. Family-based units. Also, voluntary. I think the key point is it is voluntary.

The young, the so-called subordinate or submissive animals, are not there because they're being compelled to stay by their parents, by a diet of aggression. They're there voluntarily and, in fact, have to almost ask their parents if it's OK to stay every now and again. Because, of course, they are competing for food and so on. So it's turned the whole idea of wolf society on its head.

Which had been portrayed as this violent, very rigidly hierarchical pack.

And, essentially, despotic. You know, the parents were forcing the young to stay behind. You will stay behind and help me, you won't go off and breed on your own, you will stay here and you will help us to raise your brothers and sisters next year, the year after, and so on. The way it's now seen, it's exactly the other way around. The young ask to stay, they're not forced to stay at all.

It's a cooperative culture --

Exactly.

And yet dog trainers still frequently invoke this idea that our dogs are alphas we must dominate, or be dominated by.

Yes, that's right. I mean, there is obviously a strong and very cool group of people who have been around for some years and are growing in number who have pointed out the fallacies of this. But I think they've tended to approach it from a kind of ethical point of view, that you don't really have the right to do this, that it's much kinder to the dog to train it using reward rather than punishment. And I would agree with all of that.

What I'm adding here, I think, is that it's not only a good idea from the point of view of ethics, and also cementing your bond with your dog, it's also right because that's the way the dog is apparently thinking, and also it's right because it's more effective, especially in the hands of individual owners. Owners who use all sorts of different punishment tend to end up with dogs that actually aren't terribly obedient.

It does strike me that a lot of your suggestions mirror our approach toward children. It wasn't that long ago that the idea of hitting your children was considered entirely appropriate.

Yeah, and I think you can put it in a broader cultural context. I think the additional science that's come along has come along at a time when, as you say, there is, in other areas of human thinking, and especially in child rearing, the idea that encouragement is better than punishment. It's a kind of a general ethos, which is spreading. It's timely in that sense.

So why does the idea that we must break our dogs persist?

One of the things that clearly is an issue is that the sorts of methods people administering punishment use are much more media-friendly. They make that kind of story easy to tell. People have approached me, you know, "Can we just get some TV on this?" And they film it, and then they realize it's incredibly boring to watch. Because being nice to a dog, it's repetitive, it takes time. The dog kind of looks sheepish or slightly confused at times, but other than that, doesn't react very much. Other than doing, eventually -- well, quite crucially -- doing what the trainer wants it to do. But it isn't as visually exciting as seeing Dog vs. Man. People who use a lot of punishment have that kind of built-in advantage, so I think it will take a while before this kind of approach becomes more widespread. But I'm obviously hopeful that, over time, it will.

I should make the point that there are some people on the other end of -- the other fringe, if you'd like -- of dog training, who are really espousing a kind of libertarian attitude, that dogs will kind of fit in with people if you leave them alone. And I don't support that either. I think you have to control your dog. And in that sense, I think all the trainers have it right. You owe it to the dog, and not just to yourself, to keep it under control so it doesn't run out in traffic, or injure somebody, or attack another dog, or whatever. We have to be responsible. We've domesticated these animals. We have a moral, but also very practical, responsibility to carry out. And so, training and control of the animals that we take on -- especially dogs -- is terribly important, and I wouldn't want anyone to think that I was putting forward an agenda of let the dog do what it wants.

And you believe positive reinforcement is always the way to go for dogs in all situations?

With all the research we've done -- I've worked a lot with the military, and with dogs used in places like prisons to sniff out narcotics, I've worked with people who train dogs for obedience competitions, and with people who train guide dogs -- most of them now use positive reinforcement. The research, there's not very much of it, but the research that's been done all points in the direction of the dog is much more reliable if it's been trained with reward, whether it's been trained to help a blind person around or whether it's been trained to attack terrorists. The dog that goes into that because it's fearful of its handler is less effective, and particularly less predictable, than the dog that's been trained that biting somebody's arm is fun, which is how they do it. So, I've obviously not been privy to every single bit of training that the military have ever done, but most of what I've seen has been very much focused on positive reinforcement, and seems to be very effective. As far as I know, almost all the agencies that I've certainly had much to do with, both in the U.K. and in the United States, have moved over to positive reinforcement. If the Navy SEALs can train their dogs with a lot of praise and reward, then I think anybody can.

Right. Cesar Millan and "The Dog Whisperer" is probably the biggest proponent of the old-fashioned approach toward dog training here; I'm not entirely sure how big he is over there ...

He's got quite a following over here. He did a stadium tour just over a year ago, which, you know -- big, big arenas like the size of Madison Square Garden -- and filled them, so that gives you an idea of how popular he is.

I haven't seen many of the shows, so it's difficult for me to comment on individual techniques he uses. I think, as I say in the book, I think the encouraging thing is that he's now at least in dialogue with people who espouse the opposite approaches, people like Ian Dunbar, and encouraging them to meet him halfway. I'm not sure whether they're prepared to meet him halfway; that's up to them. But I think it shows that what initially started out as essentially a guy who's using techniques that were traditional and were very widely, almost universally accepted, 20 years ago, is catching up. So I think that's all good.

You do suggest in the book that our dogs don't have the deep emotional nuance that we sometimes like to pretend that they do, or hope that they do. Though they feel intensely.

I think the science says there is a certain level of emotional experience which dogs are very unlikely to have. But that, on the other hand, given that they have, you might say, a more limited range of emotions, does that mean that they experience them less intensely than we do? I argue that they probably experience them more intensely. Because they can't distance themselves from them. They can't manipulate their own emotions in the way that we do. We watch horror movies, which are kind of scary but we know that they are not real. I don't think there's a doggy equivalent of that. So I think they experience their emotions more, maybe as a child would, more in the now, more intensely, perhaps, than we do.

I think I'll draw a parallel with the Eskimos' many, many words for snow. Maybe they have a lot of different words for different kinds of love because they feel that affectionate bond, perhaps, in more nuanced ways than we do. I don't know. It's pure speculation. But I didn't want to say that their emotional lives are any less rich than ours are. They may be less complicated. But certainly no less rich. I think they have an emotional life which goes on every waking moment, same as ours does.

Do you have a dog?

At the moment, no, but I've had dogs all my life. Pretty much up to now. I have what I call grand-dogs now, which are friends' and relatives' and my kids' dogs, and that sort of thing. And I look after those.

I grew up with a dog, and we certainly treated her as a member of the family. But we did use negative reinforcement with her. And now I of course cringe when I think of the swats on the nose with the rolled-up newspaper ...

I have the same experience as you, same reflections as you. I bought the dog-training books. When I got my first dog around 40 years ago, and got the dog-training books, which all talked about the rolled-up newspaper and a pinch on the nose, and yanking the choke chain, and I'm sure I did all those things.

A rolled-up newspaper -- such a weird idea to become so widespread!

It does its damage in the wrong hands. If you hit something very hard with a rolled-up newspaper, it just buckles, I guess that's where it comes from. But I don't know. It's lost in the myth of somewhere or other. But now, no, I put my hand up, and any responsible friend over here would put his hand up -- yeah, I punish dogs. But I punish them by withdrawing affection. The best way to get a dog's attention is to give it three treats and then refuse to give it the fourth. And you can calm and get the attention of all sorts of unruly dogs by doing that very, very quickly, and then once you've got their attention, half the battle is won.

To say that you don't use punishment when you're using these positive reinforcement techniques is nonsense. You inevitably do. What you don't do is hurt the dog. There doesn't seem to me to be any need for it. Dogs can understand all sorts of things without having to be hurt to make them understand.

You end the book on a sort of gloomy note about the future of dogs, questioning whether humans are really evolving in a good way for them, with increased urbanization, and with increasingly extreme breeding practices.

I think there's a number of people around the world -- and I wouldn't claim to be the only one, and not even the first -- to say, look, if we think dogs are a tremendous adjunct to human society, they're not just a kind of whim, they've been around for 10,000 years or more as pets (and longer as working animals), they must have a future with us. But we need to give it some thought, some careful consideration, particularly in terms of what kinds of dogs can we produce that are healthy, and happy, and fit for modern lifestyles. There's not a lot of thought, I think, being given to that, not enough to generate the dogs that we -- that most people -- actually need.

I have nothing against these little dogs, provided they're not bred to the point that their bones are too weak for their bodies, which in some breeds is the case. I'm director of charity called Medical Detection Dogs, I do their sort of science for them, and they just trained a little Affenpinscher, which is a tiny little handbag dog with a flat face, to alert somebody who has unpredictable diabetic attacks. She can carry this little dog around, even around the supermarket, and if her blood sugar suddenly takes a dive, the dog sniffs her and goes, Come on, take a blood sample. And it saves her, already, many trips to the emergency room. And this is a little dog which apparently has no nose. Nobody believed they could train it, and they trained it in two weeks.

That's amazing. And they can tell just by scent?

We think so. This is a real-life example, it's not been backed up by research. We document the training, obviously, and how effective it is, so we can continue to get money for the medical charity so it can continue to work. But it's most likely odor, in my book. There are probably changes in body language as well, but given that these things are about sudden changes in body biochemistry, I can't believe there isn't a change in the body odor that any dog, even with a little squashed-up nose, can tell apart from normal.

Shares