Animals aren't people. But, with a wave of a pen, we could make them persons. Demonstrating our special human gift for symbol manipulation, we could pass laws granting legal personhood to any animals we choose. "Poof, you're a person!"

In recent years, serious arguments have been made that we should do just that for our fellow anthropoids. As editors of "The Great Ape Project," published in 1993, animal rights advocate Paola Cavalieri and philosopher Peter Singer argue that we should grant legal equality to orangutans, gorillas and chimpanzees (presumably including pygmy chimpanzees, also known as bonobos). Now, in "Rattling the Cage," animal rights law professor and litigator Steven Wise argues for granting personhood to chimpanzees and bonobos because they are so like you. (What happened to the gorillas and orangutans? He doesn't say.)

He principally addresses their consciousness and intelligence -- their autonomy -- touching only briefly on their genetic relationship to us. (It's estimated that we have 98 percent of our DNA in common with chimpanzees, our closest genetic relatives.) Wise examines the comparison of great apes with such categories of legal persons as children, unborn fetuses and the mentally incompetent, arguing that chimps and bonobos "are entitled to the rights to bodily integrity and bodily liberty if humans with similar autonomies are entitled to them."

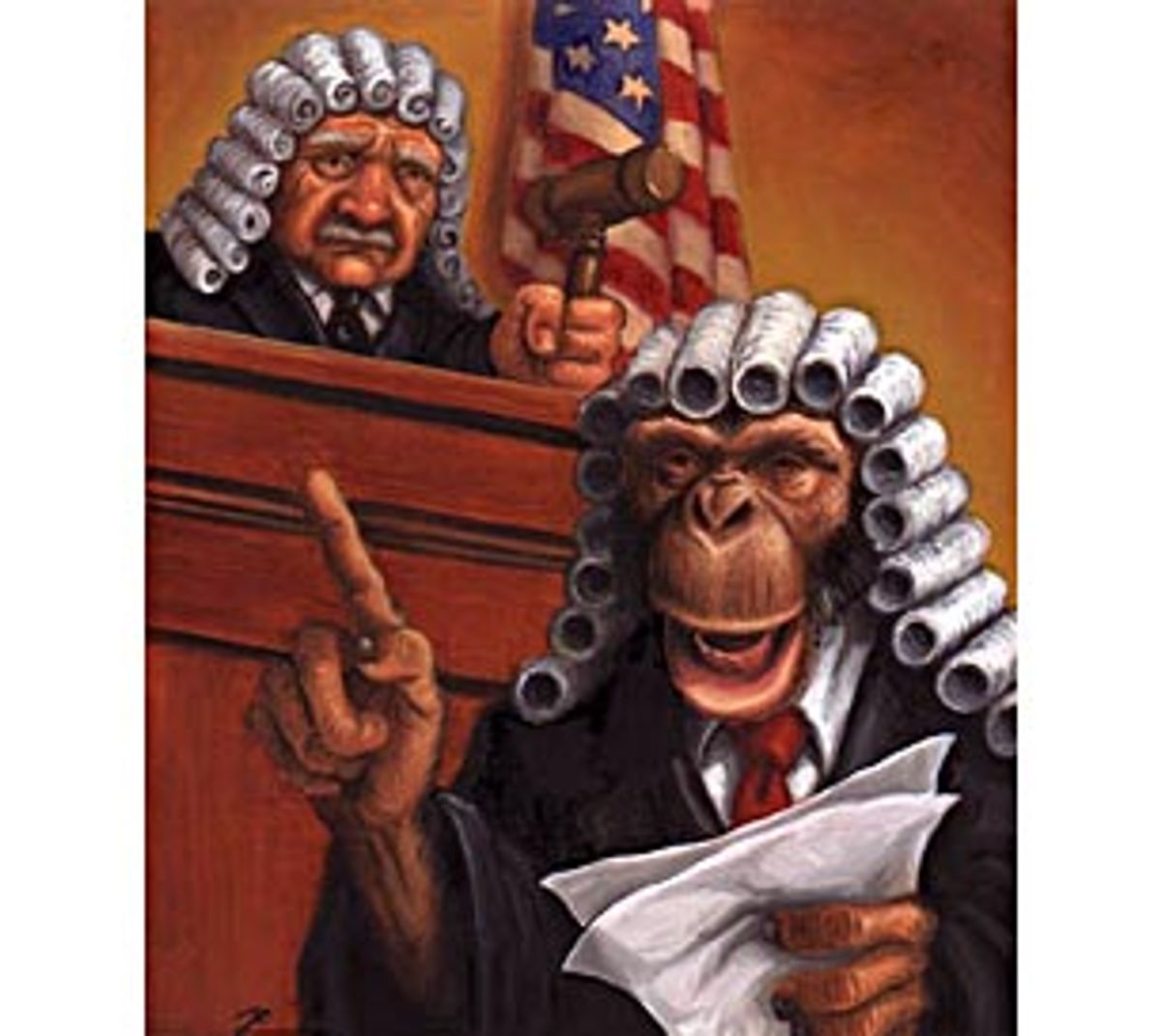

Why on earth should we involve innocent apes in our zany legal system? What could they possibly have done to deserve that? The answer is that many great apes are already enmeshed in our legal system, which defines them as property.

Lawyers struggling to prevent cruelty to animals -- a small but growing band -- are repeatedly frustrated by the limitations of feeble anti-cruelty laws. They cobble together innovative strategies revolving around charges like veterinary malpractice.

In the case of a Massachusetts couple whose seven beloved sheep were killed by a neighbor's dogs, Wise requested compensation beyond the market value of the sheep -- emotional damages. "I am talking about people who let their sheep in the house and baked them muffins," Wise told the New York Times.

Anti-cruelty laws written to curb the worst practices of farmers or pet owners seldom address the nature of different kinds of animals. While they may specify that animals can't be starved, they are unlikely to have anything to say about putting a chimpanzee alone in a small metal cage and leaving it there for a decade or two.

In 1998, a lawsuit was filed appealing to the Federal Animal Welfare Act to get companionship for an isolated chimpanzee at the Long Island Game Farm Park and Zoo, arguing that his solitude violated "the psychological well-being of primates." In what was called a groundbreaking ruling, the court ruled that a zoo visitor had standing to sue. Two years before the ruling, while the case was grinding through the courts, the chimp, Barney, escaped, bit a person, pulled up a sign and threw it at a carousel and was shot by a zoo employee.

Such legal strategies are stopgaps. It might seem that the obvious remedy is to put teeth in laws against cruelty to animals. But Wise points out that this does not address the essential conflict with the property rights of those who own the chimps. If apes are property, then owners will wish to maximize their return on their property and generally dispose of their property as they see fit. Gary Francione, an attorney who directs the Rutgers Animal Rights Law Clinic, writes, "Animals can virtually never prevail as long as humans are the only rightholder and animals are merely regarded as property -- the object of the exercise of an important human right." You lose, Bonzo.

The next obligatory part of the argument centers on how smart and lovable and reflective apes are. Almost every person who spends time with great apes becomes increasingly certain that they have mental and emotional qualities startlingly similar to our own. Bernard Rollin, a philosopher and biologist, describes an encounter with a zoo orangutan. Rollin was taken on a behind-the-scenes tour. It was a hot day and he had his sleeves rolled up. As he entered the cage, the orangutan grabbed his left hand. She ran her finger along a "deep and dramatic scar" on his left forearm, gazing into his eyes. She took his right wrist, and traced her finger along his unscarred arm, looking at him quizzically. Then she touched the scar again.

"The sense that she was asking me about the scar, as a child might, was irresistible; so irresistible, in fact, that I found myself talking to her as I would to a foreigner with a limited grasp of English. 'Old scar,' I said. 'Surgery. The doctors did it'... I confess to spending the next few hours in something of a stupor, so overwhelmed by the fact that I had, albeit momentarily, leaped the species barrier. I still cannot think or talk about that moment without feeling a chill of awe and sublimity."

Other contributors to "The Great Ape Project," including such primatologists as Jane Goodall, Geza Teleki and Roger Fouts, describe a growing certainty that the apes are astonishingly like us and unquestionably entitled to protection. The project's "Declaration on Great Apes" asks to extend "the community of equals to include all great apes: human beings, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans" in granting us all three rights -- the right not to be killed, except in circumstances such as self-defense; the right to liberty (except when criminally liable or for the protection of others); and the right not to be tortured. This last includes most painful experiments, except when the subject has given informed consent. And since the other apes can't give informed consent, that leaves humans as the only great apes you can hook up to the shock device. I don't know about you, but I generally turn down offers of that kind.

In the late 1990s, New Zealand and Great Britain banned experimentation on great apes, though neither nation has granted them legal personhood. Even Richard Dawkins, a famously unsentimental biologist, supports the declaration. Dawkins examines the biological facts of our close relationship to the other great apes and concludes that they are more like us than they are different. Most supporters of the declaration argue not from molecular similarity, but from mental similarity. Much of this discussion comes from philosophers, who litter the animal rights movement with their terrifyingly Germanic prose. Philosophers in general love to propound definitions of what it is to be a person, and philosophers who support animal rights find that the more we learn about the other great apes, the more they seem to meet the criteria.

The line that divides humans from other animals gets moved every time we learn more about the animals. Man is the animal that uses tools -- what, you say chimps, otters, even birds use tools? Man is the animal that makes tools. What, wild chimps make tools? Well, man is the animal that demonstrates mental meta-representation, self-conception, conscience, logical and mathematical ability, the knowledge that minds exist, and symbolic and nonsymbolic communication. And should be able to dance backward in high heels, presumably.

No one argues that the other great apes are as capable as we are at this stuff (which might be why we picked these criteria), but as psychologist Robert Mitchell writes, "The great apes seem to differ from human beings by degrees [of self-consciousness] rather than in kind."

Mitchell's research focuses on imitation and deception, subjects that cast light on animals' self-images and on their knowledge of other minds. He relates the story of a young bottlenose dolphin in an aquarium trying to get attention from some people on the other side of the glass. Seeing one of them blow a cloud of cigarette smoke, she went to her mother, took a mouthful of milk, swam back to the glass and puffed it out so it made a cloud around her own head. It's cute, but it also demonstrates "communication via simulation and non-natural meaning."

Deception also demonstrates interesting things about consciousness of self and others and perhaps an explicit "theory of mind." H. Lyn White Miles, a sociologist and psychologist, worked with an orangutan, Chantek, who knows some sign language. Chantek stole a pencil eraser, popped it in his mouth and pretended to swallow. To prove it, he opened his mouth and signed "food eat." But in fact -- the liar! - - he had concealed it in his cheek, where he kept it until he could stash it in his bedroom.

One can't get too outraged about the theft of the eraser or Chantek's grossly dishonest testimony, but the matter of deception raises the issue of responsibility. Primatologist Frans de Waal, who has done extensive research on the lives of captive chimpanzees and bonobos, argues that "rights are part of a social contract that makes no sense without responsibilities."

If Chantek bites someone who tries to take his eraser, should he be held responsible? What if he kills someone? Or, in the example given by de Waal, if a cheetah attacks a gazelle, can a lawyer representing the gazelle sue the cheetah?

De Waal hopes that we can ensure decent treatment of animals not by giving them rights and lawyers, but by advocating a sense of obligation and an ethic of caring. De Waal also objects to "the animal rights movement's outrageous parallel with the abolition of slavery," which he calls not only insulting but also morally flawed. "Slaves can and should become full members of society," he writes. "Animals cannot and will not."

It's true that animal advocates like Wise seem to talk about slavery endlessly. Wise makes heavy use of the comparison between remarks made about slaves and what people now say about animals. People said slaves could not feel pain, could not anticipate the future, could not take care of themselves and could not be taught to read. They were called "animated property."

What could be more insulting and racist than comparing human beings to animals? It is certainly racist to liken one race of humanity to animals, but this is not what animal rights proponents do. Instead they liken all humans to animals. Because identical remarks about slaves and animals have been made does not mean that slaves and animals are identical. Rather, it illustrates the arbitrariness of such rhetoric.

Supporters of the "Declaration on Great Apes" are undecided on exactly what rights apes should have besides life, liberty and freedom from torture. There's general agreement that we don't get to bring law and order to wild communities, wading in to stop chimp-on-chimp violence. Attorney Francione feels apes will be safe from criminal liability because, though persons, they would have to be treated as "children or incompetents." (Yet how much protection is that in an era when presidential candidates are eager to execute juveniles and the mentally incompetent to win votes?)

Wise argues that the rights of apes, at least those who live in America, will have to be restricted, even with legal personhood. They should have partial rights, the same way children, mentally retarded or autistic people have partial autonomy.

When it comes to other animals, critics ask where we draw the line. Will we be asked to grant personhood to all primates next? All mammals? All vertebrates? "Would even bacteria have rights?" asks legal scholar Richard Epstein.

Well, no. I have yet to find anyone who would deny you the chance to brush your teeth, no matter how many innocent bacteria you kill. So a line would indeed have to be drawn, and we will differ on where to draw it. But the more you know great apes, it seems, the more certain you are that they belong on the same side of the line, even if no other animals do.

And some people who express derision at the idea of considering great apes as legal persons may have overlooked the fact that our legal system treats corporations and associations as legal persons, who may therefore sue and be sued.

An enduring problem with animal rights issues is the suspicion of the hidden agenda. When someone says you shouldn't wear fur, do you suspect that if they win that battle, they will next request that you not wear leather, then that you not eat meat, then perhaps that you become a vegan and give up milk, honey, wool and other animal products?

In truth, many animal activists do have such goals for the world and hope to proceed step by moral step toward them, leading you bleating and rationalizing behind them. "Well, OK, no endangered species, but I still get fur trim on my parka. They do? OK, no fur, but I'm not giving up veal. They raise them how? OK, no veal, but I'm not giving up lobster. Really? That's so sad. OK, no lobster, but ..."

Wise, for example, makes only passing reference to animals other than chimpanzees and bonobos. While he explores the implications of personhood for chimps and bonobos, he does not examine the implications of granting personhood to some animals and not others. He has fought legal battles on behalf of animals from the muffin-munching sheep to parrots, so one naturally suspects that if the battle to cede personhood to great apes is won, he'll be back with testimonials to the wonders of other creatures.

The other great apes are not identical to us, but like us in their mental lives and in our close physical relationship. I'm not sure where I myself will want to draw the line, but I'm convinced that apes (and I would vote for all of them, not just chimps and bonobos) should be on my side of it, even if they insist on hooting and throwing things at the animals on the other side.

Shares