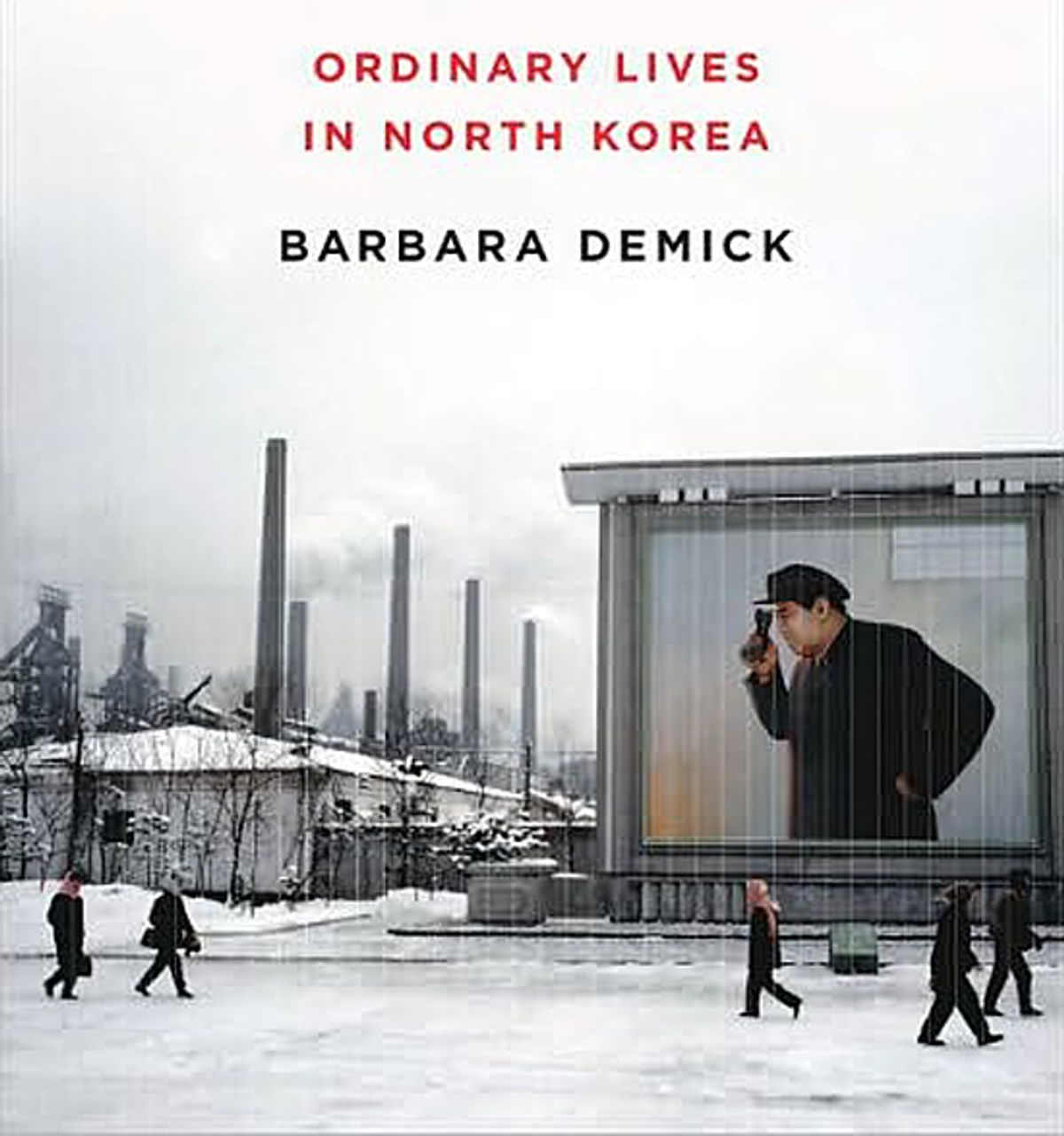

The image that opens the first chapter of Barbara Demick's "Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea" is a satellite photograph of North and South Korea by night. The southern nation is spangled with electric lights, including the vast, solid blotch of brightness that is Seoul, while the north is entirely dark except for the tiny dot of the capital, Pyongyang. The Western view of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea is mostly made up of freakish pictures like this one, official footage of goose-stepping soldiers and automaton-like crowds performing tributes to "Dear Leader" Kim Jong-Il, eerie samizdat video of crisply uniformed police directing nonexistent traffic on empty streets, the bizarre spectacle of the vacant Ryugyong Hotel (aka the "Hotel of Doom") towering over Pyongyang, and the ubiquitous socialist-realist kitsch seemingly beamed in from the middle of the previous century.

Illuminating documentary images of the nation are almost impossible to come by. Oppressive government escorts control the rare visits of foreign journalists to North Korea, and this inaccessibility is a major source of the fascination that Asia's hermit kingdom exerts. It's a demonic version of Shangri-La, that fabled paradise cut off from the rest of the world by insurmountable barriers. The darkness shown in that satellite photo is both literal (the country suffers from severe power shortages) and metaphorical: Outsiders simply cannot see what's going on in there.

But we can listen, to the thousands of North Korean defectors who have fled to China and -- to a lesser degree -- South Korea in the past decade. (Before the famine of the late 1990s, only a handful of North Koreans had dared to escape.) "Nothing to Envy" (the book's title comes from an anthem taught to every North Korean schoolchild) is built on interviews and profiles Demick conducted as the Los Angeles Times' first bureau chief in Korea. In particular, she focused on former residents of the northern city of Chongjin, a grim area known for its restive population and, due to its proximity to the Chinese border, the hometown of many defectors.

"Nothing to Envy" must do what journalism hasn't been required to do for nearly a century: use words to create pictures of scenes that cannot be captured by a camera. With an eloquence seldom found in newspaper journalists, Demick has risen to the occasion -- all the more remarkable when you consider that she hasn't seen these sights herself. She has a novelist's knack for eliciting the telling detail, as when she notes that if you went out on a moonless night in the years after the nation's electrical grid effectively collapsed, the only way you could tell anyone else was around was by the coal of their cigarette burning in the dark. There's the writing paper sold in state stores, made of corn husks that "would crumble easily if you scratched too hard," so that people wrote on paper scavenged from the margins of newspapers. And then there's Vinalon, "a stiff, shiny synthetic material unique to North Korea," of which the fatherland was ludicrously proud. Vinalon takes dye so poorly that everyone's clothes (which were mostly uniforms to begin with) were limited to drab grays, blues and browns.

The characters in this story are, as the book's subtitle promises, several ordinary Koreans. In particular, Demick focuses on a gung-ho middle-aged woman whose malcontent daughter persuaded her to defect and a pair of star-crossed teenage lovers who sustained their chaste romance through 13 years of secret nocturnal meetings and smuggled letters. (The daughter of a former South Korean POW, the girl in this couple was regarded as having "tainted blood" and therefore an unsuitable attachment for her more-privileged beau.) The world these people struggled to survive in resembled an amalgam of science-fiction tropes, part totalitarian surveillance state à la "1984," part post-apocalyptic wasteland.

As Demick points out, "North Korea is not an undeveloped country; it is a country that has fallen out of the developed world." Its inhabitants have no choice but to partake of the pre-industrial conditions that some Western elites now mourn as part of the vanished past. With the factories and electricity shut down, the air over Chungjin is pristine again, and you can see every star in the night sky. Doctors provide herbal remedies, but only because they have nothing else; furthermore, they are required to spend weeks camping out in the mountainous countryside, harvesting wild plants. Some resort to growing their own cotton in order to have bandages. Most North Koreans have never seen a mobile phone and don't know that the Internet exists.

They have also seen their neighbors, friends and relatives starve or get carted off to prison camps for offenses as trivial as joking about the Dear Leader's diminutive stature. A former kindergarten teacher Demick interviewed still suffers from crippling survivor's guilt when she remembers how she watched as her students wasted away. "What she didn't realize," Demick writes, "is that her indifference was an acquired survival skill. In order to get through the 1990s alive, one had to suppress any impulse to share food. To avoid going insane, one had to learn to stop caring." In the famine years, parts of North Korea were not so different from Nazi concentration camps, where, as Primo Levi observed, anyone who made it out inevitably had something to be ashamed of.

So ironclad was the government's control over media and foreign travel that most North Koreans believed (and some still believe) that it is worse elsewhere, and that their hardships have been imposed on them by "the American bastards" and their "puppet regime" in the south. One of Demick's sources described his astonishment when first told that a countryman had met South Korean soldiers who didn't immediately try to kill him. One of the most striking things about the stories in "Nothing to Envy" is how steadfastly some North Koreans have resisted acknowledging the extent of their leaders' lies.

In his new survey of North Korean propaganda, "The Cleanest Race," B.R. Myers insists that the ongoing support of the North Korean public for the regime doesn't reflect any great faith in communism. Instead, he argues, it is rooted in a kind of paranoid racial nationalism adapted from the Japanese fascism that flourished before World War II. The defectors Demick interviewed trace the birth of their disillusionment to their exposure to South Korean television and radio and the sudden revelation that the standard of living outside their country was much, much higher than that within. If the rest of the nation were to follow their example, the fall of the current regime would very much resemble the collapse of the Eastern bloc 20 years ago. Myers feels that the racialism at the heart of the regime's ideology will sustain it even as it fails to provide the prosperity it promises.

In either event, the inevitable merging of the two Koreas will likely be as rocky as the reunification of Europe. Even the most anticipated reunions in "Nothing to Envy" have surprising and even dispiriting results. It's blinding and disorienting, walking into the light after a lifetime in the dark.

Shares