When Patti Smith first began to release albums in the late 1970s, she seemed to have magically eluded all of the shackles imposed on women in the rock ‘n’ roll world. She was neither angelic muse nor bad-girl sexpot, a tomboy willing to be photographed in a pale peach slip, flashing a patch of unshaven armpit hair that shocked the record-store boys I knew more than just about anything any girl had ever done. Rumors went around that she claimed to masturbate to photographs of herself, a concept that baffled me; I was so naive I didn’t understand yet that people (i.e., men) masturbated to photographs, and the idea of being sufficiently aroused by one’s own image to do so was unfathomable. Fascinated, I turned out to see this intimidating person at an in-store appearance, only to have my copy of “Easter” signed by a soft-spoken urchin with a luminous smile.

“Just Kids,” Smith’s new memoir of her early life and close relationship with the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, helps explain this and other apparent contradictions. In relating her (very) gradual evolution into a rock singer, Smith gives an account of her first poetry reading accompanied by guitarist Lenny Kaye, at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village. Ordinarily self-conscious, she discovered a “submerged arrogance” that only came out in performance, “a whole other side” of herself who behaved, to her dismay, like “a young cock.” It’s impossible to imagine the Patti Smith who narrates “Just Kids” boasting about her autoerotic practices. Instead, this version of Smith is circumspect to the point of demureness as she describes her adventures in the decadent carnival of New York in the 1960s and ’70s. She is as innocent in her own way as I was when I bought that first copy of “Easter,” ferociously earnest and irresistibly moving.

As much as Smith loves rock ‘n’ roll, “Just Kids” confirms that she identifies fundamentally as a poet, specifically as an acolyte of the French symbolist Arthur Rimbaud, who died in 1891. The opening chapters of the book — with their descriptions of sitting on the stoop of the Chicago rooming house where her mother took in ironing, “waiting for the iceman and the last of the horse-drawn wagons” — have the flavor of another age, with their slightly antiquated diction and vocabulary. (Smith was born in 1946.) “I lived in my own world, dreaming about the dead and their vanished centuries,” she writes of her earliest years living with Mapplethorpe in Brooklyn, N.Y., in the late ’60s.

Her life before that, at least as she tells it, resembles nothing so much as a Hardy or Lawrence novel, with working-class parents who read Plato and supported the civil rights movement, but who couldn’t afford to take the entire family to an art museum more than once during her childhood. After graduating from high school, Smith labored at grueling nonunion factory jobs and slept in a cot in her parents’ laundry room, clutching her sketchbook and treasured copy of Rimbaud’s “Illuminations.” At 20, she got pregnant by a boy “so inexperienced he could hardly be held accountable” and gave the child up for adoption, then decided to start all over from scratch in the big city. Arriving at a New Jersey bus station, she learned that the fare to New York was twice what she had expected or could afford, but then she found a purse containing $32 in a telephone booth and made it anyway, interpreting this “last piece of encouragement” as a “thief’s good-luck sign” from an “unknown benefactor.”

In New York she slept rough for a few weeks, then finally landed a bookstore job, befriended Mapplethorpe and moved in with him. They were so broke that when an art exhibit interested them, only one would pay to go inside, absorbing the details to report back to the other afterward. They had lengthy debates over whether they could afford to buy chocolate milk, which cost a dime more than regular milk. They spent their evenings drawing together, using art supplies Smith shoplifted, and vowed never to part.

Although “Just Kids” is Smith’s tribute to Mapplethorpe, she’s the more arresting character of the pair. The child of aspiring middle-class Catholics, Mapplethorpe was an understandable tangle of ambivalence and self-doubt, craving wealth and entree into “high society” but equally driven to violate propriety with his sexually explicit and homoerotic photographs. He dragged Smith to in-spots like Max’s Kansas City, hoping to encounter his own idol, Andy Warhol, and, once he began to make a name for himself as an artist, to tony dinner parties where they rubbed elbows with the likes of Bianca Jagger. Smith had no interest in Warhol (“His work reflected a culture I wanted to avoid”) and embarrassed Mapplethorpe with her table manners, but she went along for his sake, and often made friends in the unlikeliest places.

Sex remains something of a mystery in this story; Smith and Mapplethorpe were lovers and lived together off and on for several years even as he came to accept his attraction to men. Smith mostly skirts the topic of their physical relationship, making fleeting references to “intimacy” and “passion.” She admits that at first she “knew nothing of the reality of homosexuality” and thought that she had failed to “save him” from it. For Mapplethorpe’s part, he seems to have never entirely let go of the idea of the two them as a couple (he let his parents believe they were married for years) and, on one of their last meetings before he died of AIDS in 1989, he lamented the fact that they had never had children.

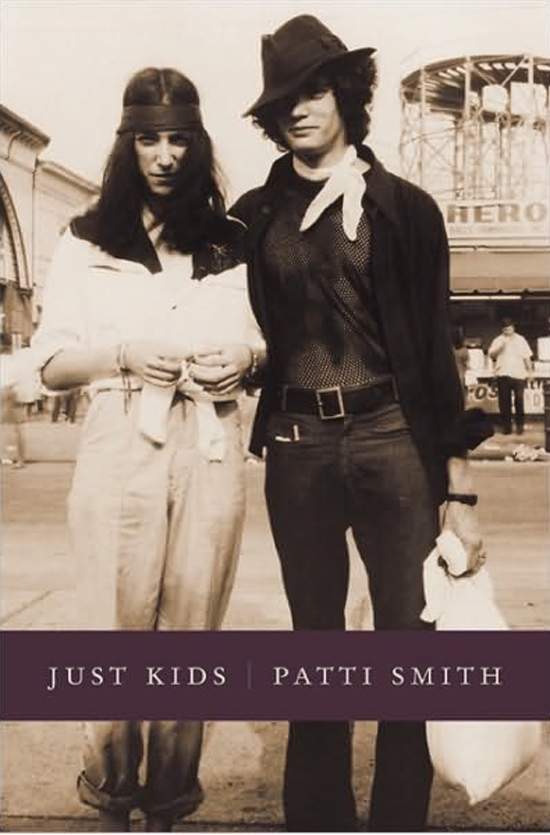

Hatchet-faced, pale and thin as a rail, a mercurial combination of ugliness and beauty, Smith has always exerted a potent, androgynous charisma. Her other lovers included playwright Sam Shepard, poet-musician Jim Carroll and Blue Oyster Cult keyboardist Allen Lanier, and in 1980 she married the guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, with whom she had two children; even Allen Ginsberg once tried to pick her up at an automat, mistaking her for “a very beautiful boy.” But she also found platonic friends and champions readily, particularly when she and Mapplethorpe lived in Manhattan’s famed Chelsea Hotel and she spent hours in the lobby, scribbling poems in her notebooks. Luminaries and big shots ranging from poet Gregory Corso to rock goddess Janis Joplin to music producer Sandy Pearlman struck up conversations and alliances with her there.

What attracted them, and what surely lay at the root of Mapplethorpe’s love for her, is Smith’s striking purity. “Just Kids” is a book utterly lacking in irony or sophisticated cynicism, and if Smith writes reverently of such personal demigods as Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones, it is not their celebrity that entrances her; she sees them only as modern-day counterparts to her adored Rimbaud. Their names are talismans and amulets in her personal cult of art. The sensation caused by her early performances with Kaye led to offers of a record deal, but she turned it down on the grounds that it had come too easily and that another of her heroes, Crazy Horse, advised against “taking spoils that were not rightfully mine.” Instead, she tried to talk Mapplethorpe’s patron into flying her to Africa so that she could search for the lost Rimbaud manuscript she’d seen in a dream.

For someone as conflicted and ambitious as Mapplethorpe, who was dazzled by glitz and often pursued for his looks, who struggled with his sexuality and believed himself to be divided into good and evil halves, Smith was surely an emotional North Star. She looked into him and saw the only thing that mattered to her and the one part of himself he believed in unwaveringly: that he was an artist. Smith’s idea of what that meant was permanently fixed in the image of 19th-century bohemia, of the starving poet as blessed, perpetual outsider. Extravagantly idealistic, she also appeared to be physically fragile, like the living embodiment of the flickering, uncorrupted creative impulse that the artists and musicians and writers around her had all felt at some point in their pasts, and hoped they hadn’t entirely lost. No wonder near-strangers felt an impulse to shelter, help and encourage her.

Ironically, Smith wound up surviving not only Mapplethorpe, but also her husband, Carroll, her younger brother and other important men in her life. “My temperament was sturdier,” she observes in “Just Kids,” explaining why she didn’t mind being the breadwinner during the first years of her partnership with Mapplethorpe, so that he could quit a job that left him too tired to make art. In that toughness, at least (and pace Dylan), she was indeed just like a woman: a whole lot stronger than she looked.