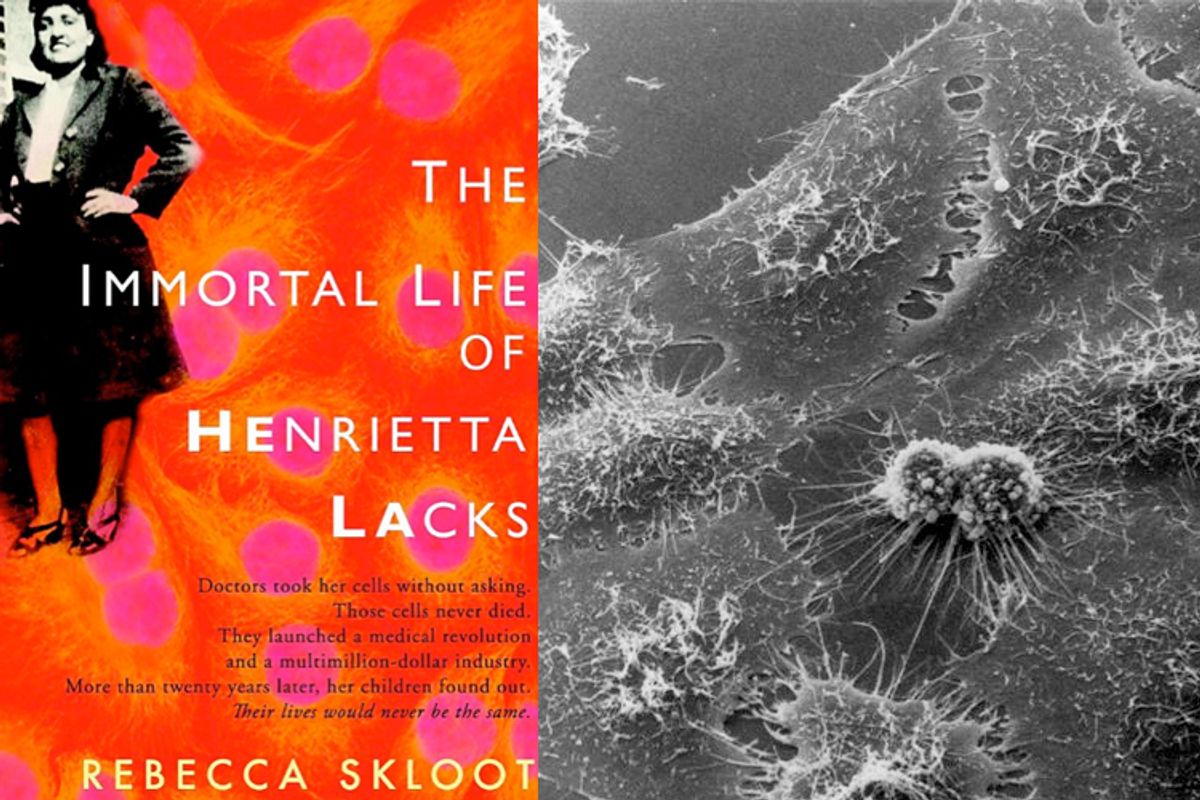

The scientific story told in Rebecca Skloot's "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is marvel enough: Lacks died in 1951, but also lives on in the form of cells, taken from a single biopsy, that have proven easier to grow in a lab than any other human tissue ever sampled. So easy, in fact, that one scientist has estimated that if you could collect all of the cells descended from that first sample on a scale, the total would weigh 50 million metric tons. Lacks' famous cell line, known as HeLa, has played a key role in the development of cures and treatments for polio, AIDS, infertility and cancer, as well as research into cloning, gene mapping and radiation.

There's a run-of-the-mill "The Cells That Changed the World" book in that premise, and one with a better claim to credibility than most of the "Changed the World" titles that have flooded bookstores since Dava Sobel's "Longitude" became a surprise bestseller 14 years ago. But "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is far from run-of-the-mill -- it's indelible. Skloot (whom -- full disclosure -- I know slightly) spent a decade tracking down Lacks' surviving family and winning over their much-abused trust, a process that becomes part of the story she tells. Actually, it often takes over the story entirely. Just as the DNA in a cell's nucleus contains the blueprint for an entire organism, so does the story of Henrietta Lacks hold within it the history of medicine and race in America, a history combining equal parts of shame and wonder.

Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman born and raised in rural Virginia, was treated for the cervical cancer that killed her in Baltimore's Johns Hopkins Hospital. A sample of her cancer cells taken during an early examination was handed over to a Hopkins researcher, George Gey, who probably never met Lacks herself. Unlike the vast majority of human cells, which almost always die soon after being removed from the body, Lacks' turned out to be astonishingly robust and easy to culture. They contain an enzyme that prevents them from automatically degenerating like normal cells, rendering them immortal, capable of dividing and multiplying seemingly forever. HeLa has provided countless experimenters with the once-rare raw materials needed to test drugs and procedures that have saved lives and transformed medicine.

But Lacks never knew her cells had been taken by Gey or why. Her family, who struggled to survive through a series of hardships that make "The Color Purple" look tame by comparison, occasionally heard from Hopkins or from journalists captivated by the HeLa story, but they had difficulty understanding what little information they were given. Then, in the '60s, a scientist discovered that most of the other cell lines being cultivated throughout the world had been contaminated by HeLa cells, and had probably been taken over by them. Hopkins researchers tracked down the Lackses to get the blood samples they needed to detect that contamination; the family thought they were being tested for the terrifying disease that had killed Henrietta. They believed that "Henrietta" had been shot into space, blown up with nuclear bombs and cloned. They worried that she might somehow be suffering through these experiences. And, eventually, they were enraged to learn that companies were making money selling vials of her cells while her children couldn't even afford medical insurance.

By the time Skloot contacted Henrietta's daughter, Deborah, the Lacks clan had been bewildered by doctors, terrified by rumors and bamboozled by con men. Deborah couldn't remember her mother, and had only the foggiest notion of how she died. Her memories of the abusive cousins who came to "take care" of her and her younger brother after her mother's death were, unfortunately, all too vivid. The loss of Henrietta -- "Sweetest girl you ever wanna meet, and prettier than anything," according to one relative -- haunted Deborah and her siblings. When outsiders unearthed the fact that they'd also had an epileptic and mentally disabled sister who'd died in an institution, Deborah's tormenting, thwarted desire to know what really happened to her mother and sister precipitated a breakdown.

The role Skloot assumed when she stepped into this narrative could serve as a textbook example for the mission of narrative journalists everywhere. "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is the story of two different worlds coexisting side by side and largely unintelligible to each other; Skloot makes it her job to build a meaningful bridge between them. A white, secular science writer from the Pacific Northwest, she explained the basics of biology to the devout, Southern Lackses and the emotional and social perspective of the Lackses to her educated readers. She drew diagrams of cells for Deborah's angry brother, and witnessed a spiritual healing of a mentally unraveling Deborah at the hands of a man who tells her he suspects Henrietta's illness was caused by voodoo. Above all, she listened to Deborah and her family, and took their anxieties and confusion seriously.

Naturally, Henrietta's story raises all sorts of issues -- of patient consent, medical ethics, the ownership of genetic material and so on. What it most impressively succeeds at, however, is allowing readers to see the world from the Lackses' perspective. Early in the book, Deborah's sister-in-law speaks darkly of how "John Hopkins was known for experimentin on black folks. They'd snatch em off the street." Deborah worries that the hospital infected her mother with cancer and that her sister might have undergone similar ordeals in the institution where she died. Sounds paranoid, but while most of the Lackses' suspicions about Hopkins are unfounded, Skloot demonstrates that such fears were far from unreasonable, given widespread attitudes in the medical profession, sensational newspaper reports and a historical record that included the likes of the Tuskegee experiments.

Most of the doctors and researchers Henrietta and her family interacted with over the years either assumed the Lackses grasped what was going on or concluded that it didn't matter. "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" does not lack for astonishing examples of professional arrogance and insensitivity. The doctor who wanted blood samples from Henrietta's descendants sent a Chinese-born assistant who spoke broken English to request them and responded to Deborah's questions by handing her a textbook he'd edited on medical genetics. As a result, she spent weeks on tenterhooks, waiting for the results of a nonexistent "cancer test." Deborah's valiant attempts to read the textbook and her determination to go back to school in her 50s so that she could understand what was going on with "them cells" are heart-rending. When, via Skloot, she finally connects with a kind, respectful Austrian researcher who gives her a tour of his lab and hands her a vial of her mother's cells, it's as if a sunbeam has finally broken through the cloud cover.

Much like Ann Fadiman's classic investigation of the botched treatment of an epileptic Hmong child in a California hospital, "The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down," "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is a heroic work of cultural and medical journalism. With it, Skloot reminds doctors, patients and outside observers that however advanced the technology and esoteric the science, the material they work with is humanity, and every piece of it is precious.

Shares