David Shields' new book, "Reality Hunger: A Manifesto," is, depending upon whom you ask, a condemnation of the novel, a celebration of the sort of remixing and collage writing that often gets slammed as plagiarism, an indictment of plot, or a defense of memoirists who fabricate. Given his infatuation with playful writing (although a playfulness so earnestly willed seems an oxymoron), Shields shouldn't be dismayed to learn that tracking responses to "Reality Hunger" across the Web is significantly more stimulating than the book itself. When you throw that many bombs, you can expect to choke on the smoke.

Above all, Shields' book yearns to be what its subtitle proclaims: a manifesto. That desire is really the easiest thing to nail down about "Reality Hunger." It's not that Shields is evasive, exactly, but he does keep dodging and feinting in celebrating the irrelevance of originality or the supremacy of the documentary mode. The book's format only accentuates this slipperiness: It contains a lot of passages cut and pasted from the work of other writers and artists. This technique, which Shields calls "literary mosaic," is meant to imitate hip-hop sampling and other kinds of musical appropriation. In the book's final pages, he explains that initially he didn't even want to identify the sources of these quotes, but "Random House lawyers" talked him into naming them in the endnotes.

Lots of assertions get made in "Reality Hunger," so many that it's easy to get lost in the maze of explaining and evaluating them. It seems true to me, for example, that reality TV, memoirs and other documentary-based forms feed a popular craving for the authentic, the unscripted and the unpredictable, even though the demand for certain formulaic storylines pressures creators to tweak "reality" into a more conventionally satisfying narrative. On the other hand, I can't endorse Shields' opinion that too much emphasis on plot is what makes contemporary novels boring and is causing a lot of people to stop reading them. Then again, the people I know who have stopped reading fiction do seem to concur with Shields that "more invention, more fabrication" is not what they want from a book. Which is why none of them, in turn, would agree with his insistence that the distinction between fact and fiction is often immaterial.

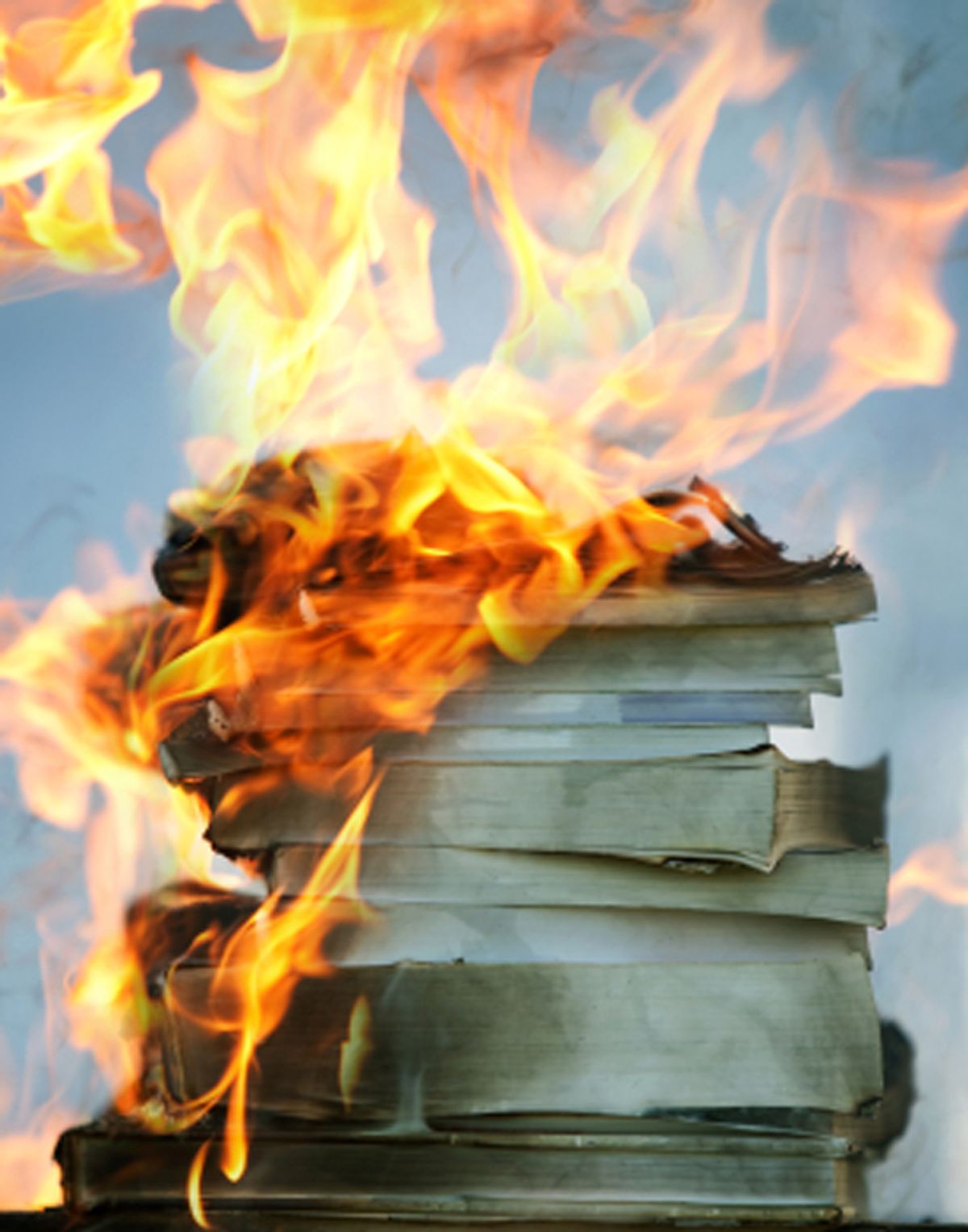

But I'm going to set aside all of those eminently arguable points for the moment and consider the manifesto-ness of "Reality Hunger," evident in such mottoes as, "The novel is dead. Long live the anti-novel, built from scraps," and "Plot is for dead people." Shields is far from alone in his taste for bold and sweeping aesthetic calls-to-arms. A manifesto makes people feel that their writing (and reading) is caught up in and contributing to some greater movement or cause -- possibly one that will be looked back upon by future generations with as much admiration as we feel today toward, say, the surrealists, the beats, or the writers who clustered around the old Partisan Review.

What really makes manifestoes exciting is that they transform the grinding labor and frequent isolation of doing artistic and intellectual work into a thrilling narrative -- which is pretty ironic, when you consider that Shields is forever announcing his impatience with and dislike of narrative. Manifestoes, of course, usually state some sort of code, such as the principles outlined by the Dogme 95 avant-garde filmmaking group. But, if anything, they are defined less by what they propose than by what they oppose -- in the case of Dogme 95, it's the artificiality of Hollywood movies and their ilk. The prevailing order, the average manifesto proclaims, has become complacent and exhausted. It must be overthrown!

This rhetoric is borrowed from war, or, more precisely, from revolution. Political revolutions justify themselves by saying the ruling order is unjust, but the artistic manifesto usually has to fall back on accusing the established art form of its day of being worn out, used up, inadequate to the important tasks of the moment. By this rationale, art is much like technology: The word processor will replace the typewriter, the CD dethrone the vinyl LP, and voice mail supplant the answering machine. Only fuddy-duddies and the terminally nostalgic will cling to the old (and therefore patently inferior) machine.

The analogy to technology is no coincidence; this model of cultural progress dates back a couple of hundred years to the Industrial Revolution. Culture is always evolving, of course, but the idea that new forms make the old ones obsolete and therefore useless is relatively recent. It's part of the core creed of modernism, a broad artistic movement insisting that art and literature needed to be entirely rethought and reconfigured to respond to the unprecedented conditions of modern life -- conditions brought about in large part by technology.

The irony is that even modernism got old. (Yes, another irony! -- you can see where postmodernism got its reputation for that.) Modernism fostered many, many transcendent works of art. It pushed boundaries, and also, as is less often remembered, established the very idea that "pushing boundaries" is what any serious art must do. (When, in "Reality Hunger," Shields points out that originality of material was not especially prized in art or literature prior to the Industrial Age, he's right; what he neglects to acknowledge is that neither was formal innovation.) The champions of various modernist movements announced that their new art would sweep away the old, but when the dust cleared, this mostly turned out not to be the case. The possibility of a stream-of-consciousness narrative, while exhilarating for a while, did not, as advertised, suddenly make it impossible to write or read a more traditional novel, and abstract art did not kill off the human appetite for representation.

This history should make anyone leery about sweeping claims that certain commonplace art forms are "dead" -- because what does that even mean? True, I feel comfortable saying that the epic narrative poem (along the lines of "Paradise Lost") is pretty well dead. Hardly anyone writes new ones and very close to nobody reads them, not even the old, good ones. But people still read and love conventional novels, even if they're culturally marginal compared to movies or, especially, television. Furthermore, the very elements of fiction that Shields denounces as hopelessly "boring" and old-fashioned, "invented plots and invented characters," remain the staple attractions of film and TV. As for the literary form that Shields espouses, the "lyric essay" -- an amalgam of fact and fiction, autobiography and reportage, fragmented and for the most part lacking a coherent linear narrative -- well, that has yet to take the reading public by storm.

This, you may interject, is hardly the point. The books at the pinnacle of the bestseller lists may still be fiction, but this conversation is not about mere numbers. Shields is speaking of serious literary art, not "The Help," or -- God forbid! -- "Twilight." He even looks down his nose at Jonathan Franzen's "The Corrections," the sort of "run-of-the-mill, 400-page page-turner" by a "middle-of-the-road" author that he is amazed people still want even though he himself "couldn't read that book if my life depended on it." (How he knows, then, that it's run-of-the-mill is unclear.) Shields just can't bear to read any kind of novel anymore!

Fine. He has plenty of company in that, even if only a vanishingly small percentage of the refugees from fiction will join him in turning to the lyric essay instead. The novel is dead to him, but so what? Can't he just go off and write whatever he wants to write without climbing up on a soapbox to make a speech about it? How does this offbeat preference of his merit a book-length manifesto? Why does this book exist?

"Reality Hunger" doesn't offer up a convincing answer to this question until Page 177, when Shields inserts a letter addressed to someone named William. It appears to have been written during some kind of professional, possibly academic, conference, and in the aftermath of a quarrel. According to the letter, William (no last name is given) told Shields that his students had expressed interest in reading novels about people coping with "incest or abuse." Shields recommended Kathryn Harrison's "The Kiss," a memoir that generated much controversy when it was published in 1997. William sniffed at the suggestion: "On principle, I'd never have one of my students read that," he said, and Shields took offense, assuming that his colleague disdained the book out of hand, simply because it was a memoir and a notorious one. "Have you read it?" he snapped back (to which I can't resist retorting: Have you read "The Corrections"?). Shields then goes on to explain to William his "frustration at times with the extremely traditional aesthetic that predominates at this conference. I find that the kind of work to which I'm the most drawn is often condescended to here."

This letter, to my mind, is the very core of "Reality Hunger," the grain of sand at the center of not only the pearl, but the oyster itself. Until I read it, I could not make sense out of the book because I could not figure out what authority Shields' manifesto wants to overthrow. Who, I kept wondering, is he arguing against? It's not the masses. He might scold the rabble for naively believing that a memoirist should be expected to deliver a factually verifiable account of his or her life, but he's just as likely to point to the success of something like reality TV as confirmation of a groundswell in the "thirst for reality." The public, however, makes for a treacherous ally, since it adores Stephenie Meyer and Stephen King, whose bestsellers are extravagantly fictional. Presumably, these works, although popular, don't count, because they aren't Art. But in that case, why should reality TV factor into the discussion?

The stock villain in most manifestoes is the "establishment." But who is the establishment these days? The culture Shields claims to speak for has undergone a radical Balkanization; there is no Paris Salon to be rejected by anymore. If the novel is "dead," as he claims, then presumably anyone who still reads, writes and values it is hopelessly provincial and permanently sidelined. Why, then, go to the trouble of denouncing them? What power do they possess? Do novels reign at, say, the New York Times Book Review? Not really; fiction advocates have long protested that their stuff gets scant play in those pages. Besides, print book reviews are fading away amid complaints of their increasing irrelevance. In an age when a thousand blogs and amateur reviews have bloomed, whatever authority once resided in print's bastions is rapidly ebbing.

In short, I couldn't figure out who was keeping Shields down and shutting him out until I read his letter to William. Much, then, became clear. In the circles of professional writers -- arts colonies, literary conferences, MFA programs, prize committees and so on -- the attitude apparently persists that the supreme artistic achievement for any prose writer is the novel. Shields used to write and read fiction, but he's lost interest in it. The semi-documentary, semi-autobiographical lyric essay is what he wishes to pursue. But his colleagues, like William, don't take it seriously, especially if they catch a whiff of that popular but still not-quite-respectable (in their eyes) genre, the memoir. The people occupying this small corner of the culture still believe that the novel is the form that really counts.

If this doesn't strike you as matter of great consequence, I feel you. Shields could have simply announced that he has lost all interest in reading or writing fiction and is miffed that some writers he knows don't entirely respect his choice. He might have gotten a nice piece in a literary journal out of that. But a manifesto -- now, that's thinking big, with drama and conflict baked right into the format! It's reality to say that you just can't work up the enthusiasm for novels anymore, but to proclaim from the rooftops that the novel is dead, that's showbiz. Even people who don't really give a shit about the lyric essay and its delights can be goaded into writing long, brow-furrowing rebuttals to that sort of thing. Because when you write a manifesto, you are, after all, telling a story, and casting yourself as its hero. It's a story every bit as familiar and traditional as the plot of the most conventional middlebrow novel: A visionary revolutionary fights for progress by bravely challenging the reactionary old guard. It's an old-fashioned tale, no doubt -- well, let's face it, it's really pretty hokey. But it still plays.

Shares