Regular readers of this column may recall that each week I choose one book to recommend from among several titles in the same category; if I seldom mention the runners-up, it's because most of the time they're not especially relevant. Looking at fiction this week, however, it seemed as though every book I cracked was about a man run aground on the shoals of midlife, trying to figure out if it's worth carrying on in the face of a daily litany of humiliation and loss.

Some readers react with knee-jerk scorn to this theme — reminded, I think, of that time in the mid- to late 20th century when a generation of celebrated male novelists produced novel after novel about aging goats (usually college professors) finding redemption in the arms of young babes (usually college students). But times have changed, and manhood is an even trickier proposition than it used to be; only Philip Roth still believes in the ol' saved-by-the-booty formula anymore. Younger writers know that won't wash, and as a result the literature of the masculine midlife crisis feels at once richer and riskier than ever before.

Knowing, self-deprecating humor is the default approach these days. Take Sam Lipsyte's satire about a failed artist turned academic fundraiser, "The Ask," a novel so caustic you might want slip on a pair of safety gloves before turning its pages. Milo Burke, Lipsyte's narrator, is emasculated both at home and abroad, from the wife who withholds sex and casually cheats on him to the third-rate university that keeps him on only at the insistence of an old friend turned philanthropist intent on jerking his chain. Lipsyte's second novel, "Home Land," also featured a perpetually bullied (though younger) narrator, and there are readers who find his well-turned prose and grotesque scenarios hilarious. I am not, alas, among them. The hammering, ground-in nastiness of "The Ask" strikes me as overly grim — Neil LaBute meets Martin Amis — but if your idea of fun is the kind of novel where male co-workers routinely greet each other with questions like, "What's the matter, your pussy hurt?" then by all means, have at it.

Chances are I'd be recommending James Hynes "Next" to you this week, if not for a frustrating conflict of interest: Hynes (whom I've never met), blurbed my own book. Suffice to say that this novel about another put-upon, midlevel university administrative worker is more fully rounded and less claustrophobic than "Ask," with a wallop of an ending that has been justly praised by those reviewers who lack the good fortune to be encumbered by Hynes' generosity.

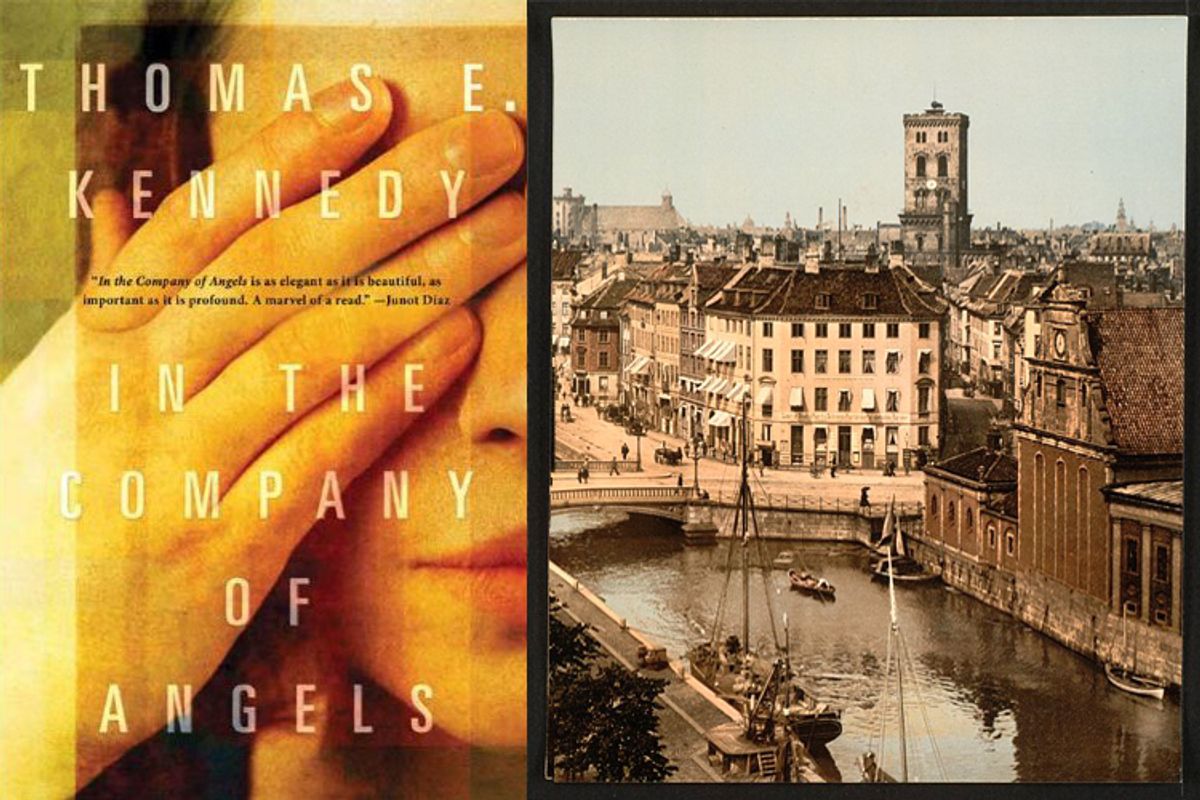

Which brings us to this week's choice, Thomas Kennedy's "In the Company of Angels," definitely not a satire. The gravely injured 50-something man at the center of this novel has infinitely better reasons for losing faith than Lipsyte's and Hynes' narrators do. His name is Bernardo "Nardo" Greene, once a teacher of literature in his native Chile, who, as a result of discussing the work of a radical poet with his students, was imprisoned and tortured by the Pinochet regime. The novel takes place in Copenhagen, where Nardo has sought asylum and receives treatment from a psychiatrist who narrates some of the chapters. Other chapters are told from the point of view of Michela, a Danish woman who frequents the same cafe as Nardo, as well as Michela's dying father and her callow boyfriend.

The style of "In the Company of Angels" is, like its somewhat unfortunate title, so earnest as to seem almost artless; by the standards of contemporary literary fiction, it's often hopelessly on-the-nose and unsubtle in describing its characters' inner lives. Yet this in no way detracts from the novel's power or its tractor-beam-like ability to lock the reader into the unfolding drama of Nardo's recovery, a fragile structure that's always on the verge of disintegrating into despair.

What this novel reminds me of, surprisingly enough, is Stephen King — though not King's supernatural apparatus or breakneck action, and certainly not his slangy, strip-mall prose. What King and Kennedy (an American who lives in Denmark) share is an interest in the idea of violence as an occupational hazard of masculinity. For this reason, there is a seeping dread that crawls through the lives of the characters in "In the Company of Angels," much like the demonic forces that infiltrate the suburban idylls of King's novels, an apprehension that cruelty and domination might be contagious and that even victims are capable of unwittingly spreading the infection. Eventually, Nardo's therapist comes to believe that he can hear his patient's chief torturer whispering taunts to him when he's at home with his wife and kids, polluting the sanctum of family life with a knowledge of human evil at its most extreme.

Every character in "In the Company of Angels" is battling that evil in one way or another, and none of them is entirely free of it himself. "You will never again be a man to a woman," the chief torturer told Nardo, and although he was speaking of physical damage, it is the experience of utter helplessness and degradation that has wounded this once-respected teacher most deeply. Such impotence is utterly incompatible with his previous understanding of manhood; therefore, he must be unmanned. The urge to cancel out a shaming weakness with some act of force is a temptation that all the men in Kennedy's novel face. If they succumb, they will only perpetuate the contagion, but to transcend violence requires an imaginative courage difficult to muster.

Trauma isn't an unusual subject in contemporary fiction, but more often than not, it's handled in a sentimental, even precious fashion (Chris Cleave's "Little Bee," Jonathan Safran Foer's "Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close") through characters who are children or have a charming, childlike naivete and an uncomplicated relationship to their own suffering. Kennedy, who worked for a Copenhagen rehabilitation center for torture victims for several years, is much more convincing in rendering the aftereffects of unthinkable ordeals. "In the Company of Angels" is a novel about grown-ups, people battered and dinged by life, painfully aware of their own responsibility, whose understanding of their past never stops evolving. It's the dignity of their adulthood — the elusive prize at stake in any midlife crisis — that makes them so admirable and, above all, so moving.

Shares