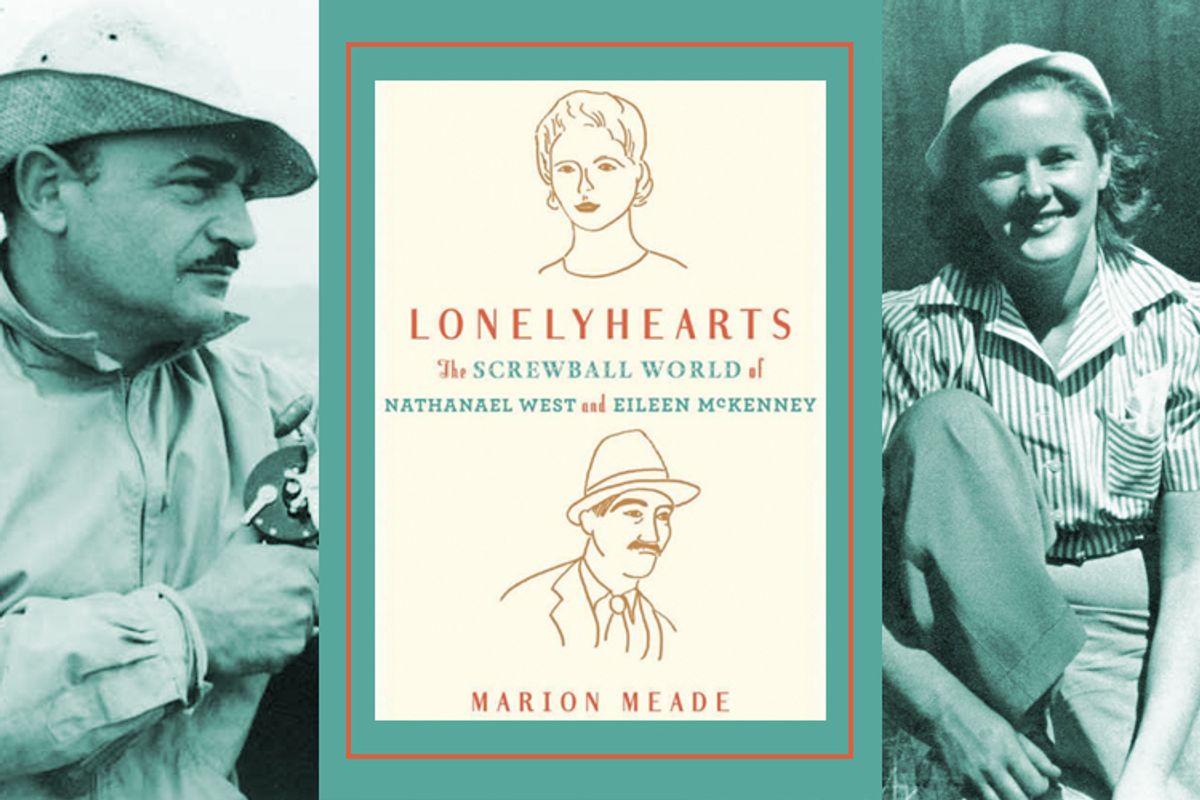

Marion Meade's "Lonelyhearts: The Screwball World of Nathanael West and Eileen McKenney" is a love story of sorts, although the two principals don't even meet until the 21st chapter, and are killed -- in a car crash, after knowing each other for about a year -- by the last. One member of the pair was famous when they died in 1940, and the other was ... well, not so much. In time, though, their status as public figures was reversed. Posthumously, West came to be celebrated as the author of the quintessential apocalyptic novel of Hollywood, "The Day of the Locust," while his bride, the inspiration for the highly fictionalized autobiographical bestseller "My Sister Eileen," has lapsed into relative obscurity.

"Lonelyhearts" could also be labeled a literary biography, although Meade's take on West's fiction is a bit crude, and the retro-slangy voice she adopts to tell the tale has driven at least one critic to distraction. (I kinda like it myself.) But what makes her book fascinating is more sociological and historical: It opens a window onto the lives of writers in 1930s America as they struggled with anxieties, pretensions, temptations and myths that confound our culture to this day. "Lonelyhearts" works not in spite of its crass, gossipy aspects, but because of them. Figuring out how to turn vulgarity (that is, democracy) into art, and how to make art in the midst of vulgarity has been the American literary project since we gobbled up our frontier. No one knew that better than Nathanael West.

Born Nathan Weinstein, the only son of a prosperous Manhattan real estate developer, West was an outrageously spoiled child who spent much of his youth getting over the idea that he shouldn't be expected to work or show up on time or in any other way trouble himself to get by in the world. (The Depression did a lot to revise this attitude.) His domineering philistine of a mother instilled in him a streak of bumptious misogyny and a contempt for his parents' generation of Russian-Jewish strivers, abundantly evident in his fiction. Meade sees a lot of homoeroticism in West's work and some signs of same-sex activity in his medical history, but most of his carnal encounters seem to have been with female prostitutes -- and he had multiple cases of the clap to prove it. He was dreamy, physically clumsy, a natty dresser and (fatally, alas) a lousy driver.

Infatuated with Russian novels as a boy, West started out as the sort of an aspiring author who thought he had to relocate to Europe to produce anything great. (One of Meade's more inspired uses of biographical research explains that the week West spent hanging out in Parisian cafes hoping to rub shoulders with serious writers like James Joyce was the same week Joyce spent sprawled on his sofa, reading Anita Loos' proto-chicklit classic, "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.") In opposition to his reverence for high art, West had an iconoclastic impulse to thumb his nose at "litracher" and cram his novels with grotesqueries and colloquialisms. He was particularly partial to lecherous dwarves and cartoonishly beefy lesbians, and his characters say things like "She can't give me the fingeroo!"

A penchant for the "-eroo" suffix appears to be contagious, since Meade's account of West's rocky publication history is full of references to such "switcheroos" and "twisteroos," as the publisher of his second novel, "Miss Lonelyhearts," going bankrupt just as the book was debuting to strong reviews. When West finally befriended some literary luminaries (Dorothy Parker, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Edmund Wilson), it seldom did him any good. As a hotel manager in New York, he'd let Dashiell Hammett stay in one of the rooms free of charge, but once Hammett had made it in the film industry, he not only reneged on a promise to help West get screenwriting work but publicly humiliated him as well. Fingeroo!

The prominent writers of the 1930s had a fantastically contorted relationship to Hollywood. West's brother-in-law, the humorist S.J. Perelman, reviled the movie business as a "gigantic rat fuck," but like Parker, Fitzgerald and the rest, he could not resist the siren song of a Hollywood paycheck. West's good friend, the novelist Josephine Herbst, regarded the film industry as a form of quicksand that sucked in promising novelists -- each one swearing to escape and write something "real" once he'd saved up enough cash -- and never let them go.

Policing the supposedly unbridgeable gulf between entertainment and art still obsesses much of American literary culture, to enervating effect. West, in contrast to his peers, found his best and darkest subject in Hollywood's human detritus -- the hopefuls, hangers-on and dead-enders on Vine Street, who watched everyone walk by with "eyes filled with hatred." As he saw it, legit publishing had jerked him around, while the movie business not only rewarded him handsomely, but also provided the structure that made him much more productive.

Besides the negative example of the movies, American writers of the time were preoccupied with communism, which entered West's life in earnest when he took up with Eileen McKenney. Eileen's sister, Ruth, was a deeply committed member of the Communist Party. To make money while she toiled away on a history of the rubber workers' union in their home state of Ohio, Ruth wrote bubbly comic essays for the New Yorker about living with Eileen in a basement apartment in Greenwich Village, surrounded by wacky neighbors.

Dark-haired Ruth and blond Eileen were cast from childhood in the roles of smart sister and pretty sister, respectively. In her essays, Ruth accentuated those roles, transforming sunny Eileen into a gorgeous but ditzy heartbreaker and her manic-depressive self into the plain and pragmatic straight woman. Thus, she spun the sisters' early experiences in New York into a hugely popular blend of "Sex and the City" and "Seinfeld." (After Eileen's death, "My Sister Eileen" became a hit play, which in turn became the basis for two movies, a TV series and the Broadway musical "Wonderful Town.") Initially indifferent to politics but anxious to prove herself more than a dumb blonde, Eileen succumbed to the knee-jerk political correctness drummed into her by Ruth.

Although West attended some Party study groups to please Eileen, he had no use for utopian schemes; Herbst characterized him as "a nihilistic pessimist." (Perhaps Eileen would have eased up herself had they more time together.) West understood that mass culture had spawned a scary hunger for borrowed and processed "authenticity," and this makes his novels appear, in the words of the novelist Jonathan Lethem, "permanently oracular," anticipating such piranhaesque spectacles as reality TV and Gawker. Against the urge to idealize writers of the past, "Lonelyhearts" presents a portrait of a literary milieu as double-dealing, bitchy, hypocritical and self-deluding as pretty much every conglomeration of ambitious artists since the dawn of time. It certainly was no better than our own. The switcheroo?: Ours is no worse.

Shares