"There is no way a ten-cent white boy could develop a plan to kill a million-dollar black man," said the civil rights leader James Bevel of James Earl Ray, the man who assassinated Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. Even if you aren't inclined to credit the conspiracy theorists on this one -- and Hampton Sides, the author of a new book about Ray, "Hellhound on His Trail: The Stalking of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the International Hunt for His Assassin," is not -- you can see how the pairing of killer and victim would stick in the craw. Ray was a nonentity, a toxic loser from a long line of the same, incapable of forming even the most basic relationships, while King had the power to capture, embody and mobilize the better self of a nation.

Sides' meticulous yet driving account of Ray's plot to murder King and the 68-day international manhunt that followed is in essence a true-crime story and a splendid specimen of the genre — a genuine corker. At its center is the enigma of James Earl Ray, who could be crafty one moment and appallingly stupid the next. For Sides (the author of such popular narrative histories as "Ghost Soldiers" and "Blood and Thunder"), the King assassination has the added interest of being "the pivotal moment in the place where I come from," Memphis, Tenn., although it must be said that the chapters about King himself are the book's weakest aspect. There's really only one point where the worlds of two men as different as Ray and King could intersect, and that's a bullet.

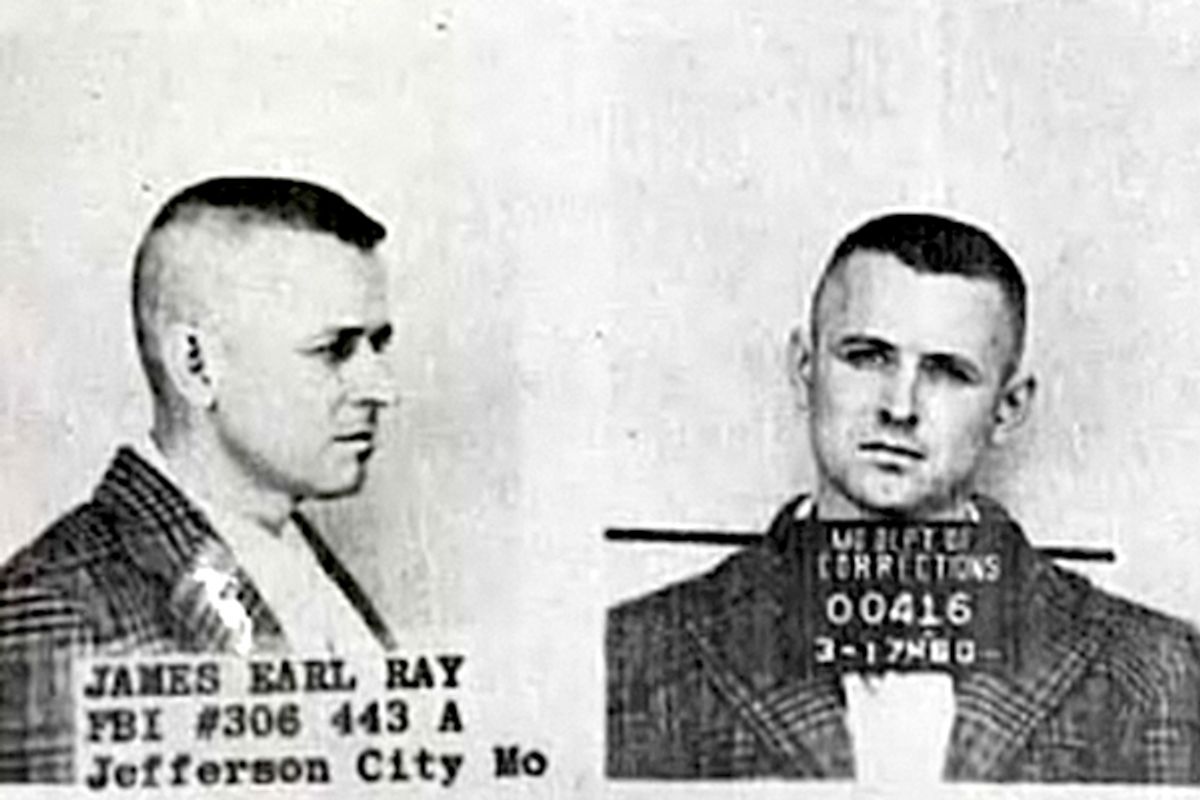

As for Ray himself -- whose real name doesn't appear in "Hellhound on His Trail" until Page 321, in the last line of the 40th chapter -- Sides deftly constructs the book so that the killer's character becomes the mystery. Ray starts out in the first chapter as a nameless convict, "Prisoner #00416-J," who escapes from the Missouri State Penitentiary at Jefferson City by hiding in a crate of freshly baked bread. After that, Sides refers to him by whichever of the many aliases the man used as he wandered from Puerto Vallarta to Los Angeles to Atlanta to Toronto to Lisbon and finally to London, where he was apprehended by a sharp-eyed Scotland Yard detective while trying to board a plane for Brussels.

Sides' ingenious method ensures that a reader who hasn't already made a study of Ray can judge him only as did the people whose lives he glided through: by his behavior. He always dressed fastidiously in suit and tie, though he invariably lived in cheap hotels and flophouses. "No matter where he was in the world," Sides writes, "his radar for sleaze remained remarkably acute." He avoided socializing or having his photo taken, cultivating a "bland and retiring" appearance and personality that made him eminently forgettable; even the plastic surgeon who gave him a nose job couldn't remember anything about the guy.

Ray had a penchant for shabby and crankish self-improvement schemes, enrolling in a bartending school and taking dance classes and a correspondence course in locksmithing. He carried a battered paperback copy of a self-help book, "Psycho-cybernetics," by Dr. Maxwell Maltz, everywhere he went and tried both psychotherapy (a treatment no doubt impaired by his reluctance to admit he was a fugitive from justice) and hypnotism. One of the hypnotists he consulted (an individual with the extraordinary name of the Rev. Xavier von Koss) pegged Ray as belonging to "the recognition type. He yearns to feel that he is somebody." Yet by both necessity and (at least some of the time) inclination, he avoided making any impression on anyone.

Wherever Ray lived -- and for much of "Hellhound" it's in Los Angeles -- he frequented whorehouses, strip joints and red-vinyl-upholstered "lounges" with names like the Sultan Room or the Rabbit's Foot Club. This is the same Angeleno demimonde that James Ellroy often writes about; Sides evokes it vividly, but without Ellroy's skeevy relish and the longing for several hot showers that Ellroy novels frequently inspire. Whenever he can, Sides imparts the details that make Ray's seedy life palpable, from the groceries with which he stocks his hideout in an Atlanta boarding house (canned milk, bottled French dressing and frozen lima beans) to his splurge on the $6.24-per-night New Rebel Motel just outside Memphis on the eve of the assassination. (Though a true aficionado of cheap motels would know that the brand of miniature soap they provide is not "Cashmere," but Cashmere Bouquet.)

The people Ray associated with ("knew" seems an overstatement) during the year between his escape and the assassination were a sundry assortment of misfits and kooks (he made a road trip with a fellow who talked to trees and claimed to have cured a woman's arthritis by burying her panties in the backyard). He most likely supported himself with petty crime: stickups and low-level drug deals. But he also became passionately involved in the presidential campaign of segregationist, and former Alabama governor, George Wallace.

Ray's enthusiasm for Wallace -- a trailblazer for Sarah Palin and similar demagogues capitalizing on white working-class resentment -- is what makes his story more than just the tale of a hate-fueled creep who struck down a great man (though it's that, too). Sides notes that Ray must have had help on two or three occasions, probably from his brothers, but perhaps also from equally racist wingnuts who shared his so-called values, whether or not they actively collaborated on his one major crime. In Wallace's California campaign offices, Ray found reinforcement for a paranoid political mind-set that was, as Sides puts it, "composed of many inchoate gripes and grievances."

Something similar could be said of the obsessions of J. Edgar Hoover, King's great nemesis within the government. The portions of "Hellhound on His Trail" devoted to Hoover and the FBI are, tellingly, far more organically integrated into the book's main narrative than the chapters on King could ever be. You don't have to believe that the government played an active role in King's assassination to recognize that Hoover was really just a more effective and powerful version of James Earl Ray. Exalted and cleaned-up bigots like Hoover provided tacit moral support for fringe dwellers like Ray, just as they do today.

King and his lieutenants and friends, for all their shortcomings and infighting, were operating on a different historical level than the likes of Ray and Hoover. They were heroes, trying to redraw our shared image of humanity into something bigger, braver and nobler than it had ever been before. This truth shines through even as "Hellhound" moves past King's assassination and into the investigation, recounted by Sides as a tense police procedural. When reporters at the funeral for Robert F. Kennedy informed Coretta Scott King that her husband's killer had finally been caught, she didn't waste a word on James Earl Ray. She simply "smiled the sad, wise smile she had perfected through two months of widowhood" and walked away.

Shares