You know Frank Mackey's type. You've met him many, many times before, in hundreds of films and TV series and in dozens of crime novels. He's a police detective, in Dublin, and he's street-, rather than book-smart. He Doesn't Play by the Rules, which means that he's always ticking off The Brass, and, yes, he's something of a hothead, but that's because he can't stand the politics, and justice is so hard to come by for the innocent victims of this dirty world. He Gets the Job Done, Whatever the Cost, and his obsession with this has left him with a broken marriage under his belt. He has a lot of dark, haunted moments. But then there's Holly, his 9-year-old daughter, the one unsullied thing in his life; he'd do anything to protect her from the ugliness he's witnessed.

In other words, Frank looks like one of crime fiction's stock crusader types (although, thank god, he hasn't got a murdered family to avenge, the cheapest, tiredest device in the TV screenwriter's toolbox). He's the guy Raymond Chandler was talking about when he wrote, "Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid."

Frank, however, is in a Tana French novel, an environment that makes Philip Marlowe's L.A. look like a church picnic. French herself doesn't play by the rules, and the prime rule of crime fiction, no matter how grisly, cynical or edgy, is that the plot begins with a disruption of order (the crime itself) and ends with the restoration of it, albeit in some slightly battered form. The guilty parties are identified and usually punished, secrets are unearthed and, above all, the world returns to intelligibility, however bitter the message it has to tell.

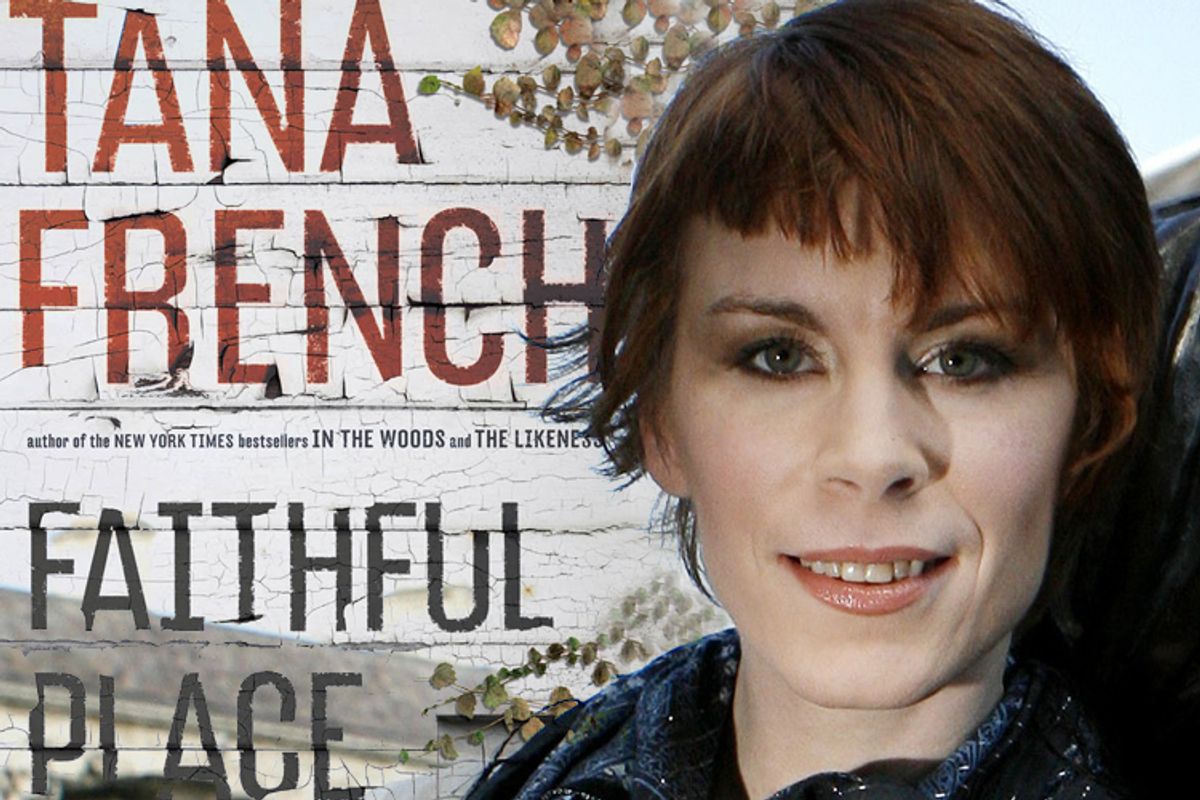

In French's previous two novels -- the mesmerizing "In the Woods" and "The Likeness" -- and now with her third, "Faithful Place," she has introduced the insolvable and the uncertain into the rigorous mathematics of the detective story; she's the Kurt Gödel of crime fiction. A thread of the uncanny runs through "In the Woods," a thread that got finer in "The Likeness," and has in turn entirely vanished from "Faithful Place." But, as in those earlier books, French considers the possibility that some things can't be known or fathomed; in "Faithful Place" it's the detective, as much as anyone else, who simply refuses to see.

Frank is a minor character from "The Likeness," the boss of the Undercover Squad, a team whose work allows French to burrow into the puzzle of identity and its fragility, how easily it can become unmoored and capsize. As in the previous two novels, "Faithful Place" has a murderer who will be identified, but in the process of discovering that truth, the detective's own psyche will be dismantled. Detective fiction's legions of brooding sleuths have paid lip service to Nietzsche's observation that if you look long enough into the abyss, the abyss starts looking back. In French's novels, the person looking becomes the abyss.

Faithful Place is a cul-de-sac in a part of Dublin called the Liberties, once synonymous with poverty and working-class desperation. "Everyone I grew up with was probably a petty criminal, one way or another, not out of badness but because that was how people got by," Frank observes. He hates Faithful Place not for the crime but for the pettiness -- the pervasive gossip ("a competitive sport that's been raised to Olympic standards") and the narrow, Catholic censoriousness, the shriveled expectations and the cheap melodrama. His father is a brutal drunk and his mother has a black belt in manipulation with added superpowers in guilt, disapproval and schadenfreude. That's why, once he got out at the age of 19, Frank never came back and has kept Holly scrupulously away from his folks. "You don't meet my family," he explains to his middle-class ex, "you open hostilities."

Frank meant to run much further away; he planned to emigrate to England with his girlfriend, Rosie, on the night he left for good, 22 years ago. But Rosie never showed, and he'd always assumed she decided to leave without him. "Rosie Daly dumping my sorry ass had been my landmark," he says of this turning point, "huge and solid as a mountain." He blamed his "crazy" family for scaring her away. He never got out of Dublin, but he could not have settled on a more emphatic way of sticking his thumb in the collective eye of Faithful Place than by becoming a cop.

So when Rosie's mouldering suitcase and then the bones of Rosie herself turn up in a derelict house on Faithful Place, Frank feels the mountain of that ancient rejection shift, "flickering like a mirage and the landscape kept shifting around it, turning itself inside out and backwards; none of the scenery looked familiar any more." He enters into a complex and destabilizing negotiation with his own past and its legacy as he searches for Rosie's killer. He sees his parents again, sits on the stoop with his four siblings, feeling how "we fit together like pieces of a jigsaw," and tries to ignore the way the painstakingly constructed barrier between himself and Faithful Place begins to erode. The more he tells himself that he's utterly changed, the more it becomes apparent that he hasn't.

French's hypnotic storytelling remains in full force in this novel, despite having shaken off the dreaminess that suffused "In the Woods" and "The Likeness." This is Roddy Doyle territory, an excavation of that particular torture experienced by those who want to break out of a hopeless, working-class world but keep getting sucked back in by the loyalty that is its one redeeming quality. "Faithful Place" is wrenching to a degree that detective fiction rarely achieves: Frank -- a cocky devil who prides himself on his skillful lying and ability to play other people -- gets pulled apart psychologically as he pursues Rosie's killer, and the reader undergoes it with him. By the end, it's difficult to distinguish what the real crime is or who committed it.

Which is not to say that French doesn't solve the novel's technical mystery or that the answer isn't tightly cinched into her larger themes. Like Kate Atkinson, who has grafted the contemporary novel of manners onto the bones of the detective story in her Jackson Brodie series, French sticks to the genre's brief while conveying it into new territory. But where the Brodie books are all pretty much the same in tone and subject matter, French does something fresh with every novel, each one as powerful as the last but in a very different manner. Perhaps she has superpowers of her own? Whatever the source of her gift, it's only growing more miraculous with every book.

Shares