In the summer of 1979, an earthen dam over the town of Church Rock, New Mexico, broke, flooding the arroyo below and then the bed of the Rio Puerco (an intermittent stream) on the southern border of the Navajo Nation. It was a small flood, but a dangerous one. It burned the feet of a boy who stepped into it, and caused sheep and crops along the banks to drop dead. That's because the pond it came from had been used by a nearby uranium mine to store the tailings (residue) of its excavations -- the water kept the radioactive dust from blowing away. The 93 million gallons of contaminated water that poured into the Rio Puerco remains the largest accidental release of radioactive material in U.S. history, bigger than the notorious Three Mile Island reactor meltdown that occurred 14 weeks later.

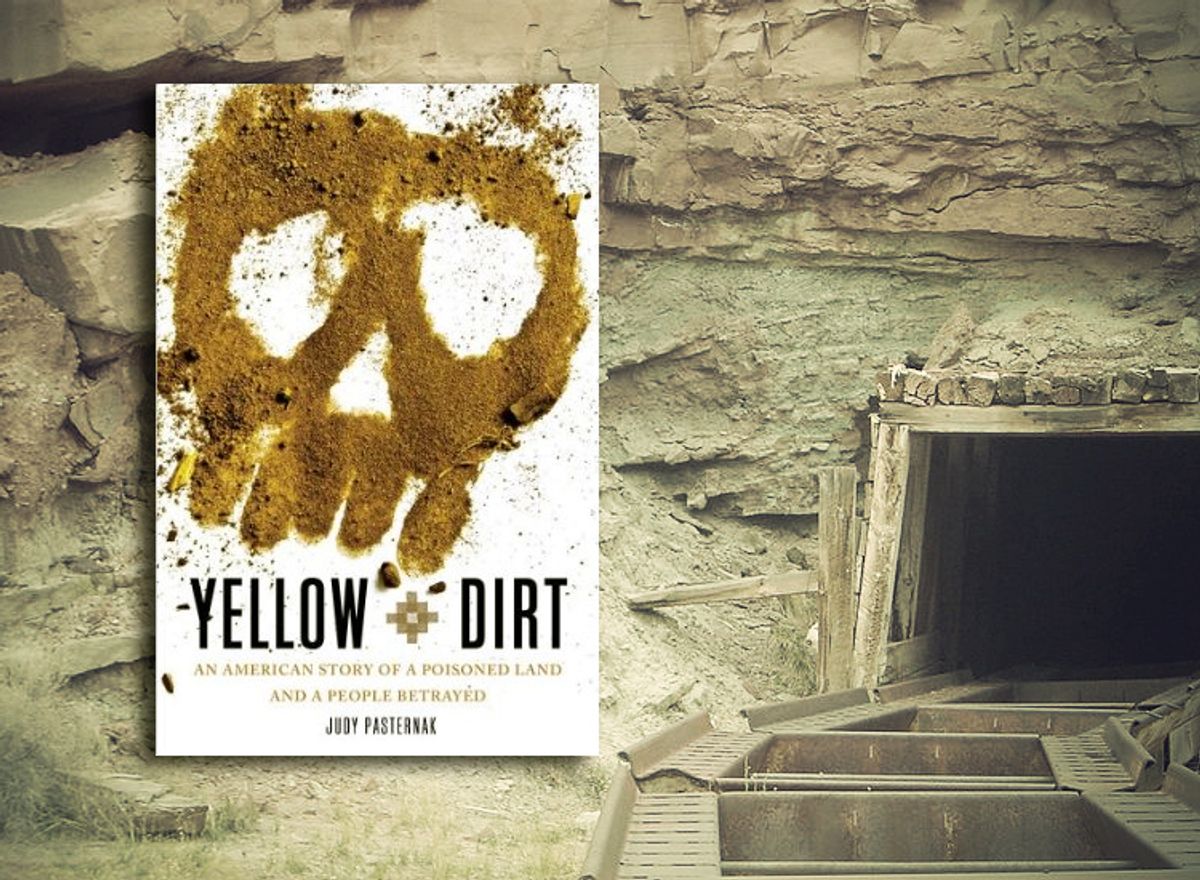

The Church Rock flood is only one incident among many in the "slow-motion disaster" investigative journalist Judy Pasternak comprehensively recounts in her chilling new book, "Yellow Dirt: An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed." Based on a prize-winning four-part series she wrote for the Los Angeles Times, "Yellow Dirt" begins during World War II, when secretive government surveyors first appeared on the remote reservation, supposedly looking for deposits of an ore called vanadium, used to strengthen steel needed for the war effort. Uranium was the real prize, and after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the ramping up of the Cold War, the American demand for the radioactive substance boomed.

The Navajo Nation and the area around it contained some of the richest deposits of uranium ore in the world, and certainly the most conveniently located. For about a decade, various corporations and government agencies reaped 1.4 million tons of uranium ore from the Monument Valley region alone; Pasternak makes a single mine there, known as Monument No. 2, her primary focus. The mining operations were relatively rudimentary, and by ordination of the tribal government, worked almost entirely by Navajo men. Even the cheapest and most elementary safety practices, such as wetting down blast areas to keep the miners from breathing toxic dust, were neglected in the rush to satisfy the Atomic Energy Commission's insatiable appetite for uranium.

By the 1960s, the need tapered off, and the mining companies blithely abandoned the sites, leaving piles of radioactive tailings lying around for Navajo kids to play on and their parents to scavenge for conveniently sized rocks with which to build houses, ovens and cisterns. The dust and gravel made seemingly excellent concrete for floors. Monument No. 2, once a mesa, had been nearly leveled, its uranium-laced innards exposed to the open air, reduced to what Pasternak characterizes as a "radioactive pit." Old quarries filled up with rain- and groundwater, new "lakes" from which local residents watered their herds and gratefully drank.

The next boom, unsurprisingly, was in cancer rates (previously so low among the Navajo that they were thought to be miraculously immune to the disease), and in a birth defect, christened "Navajo neuropathy," that caused children's fingers to fuse together and curl into claws. Still, it took decades for the cause to be fully recognized and even longer for it to be addressed; it wasn't until 2008 and under the lashing of Rep. Henry Waxman, that the federal government made serious efforts to clean up the mine sites, purify water supplies and relocate families living in houses built from radioactive materials.

The challenges in telling this story are manifold, and Pasternak doesn't always conquer them. There were so many contaminated spots, so many minor and major players, so many corporations that are then swallowed by other corporations, and so many government agencies and officials that the unfolding tragedy becomes a Kafkaesque tangle of names, acronyms, institutional rivalries, regulatory loopholes, legal boondoggles and jurisdictional buck-passing. From the very beginning there were renegade voices -- white as well as Navajo -- calling for greater safety precautions in the mines, testing of the land and water, studies of the cancer clusters and so on, but each one got slapped down, outmaneuvered, shut out and otherwise thwarted by self-interested supervisors and shortsighted authorities -- Navajo as well as white. This is no "Erin Brockovich," with a plucky hero triumphing over powerful, mustache-twirling baddies.

Nevertheless, "Yellow Dirt" has the cumulative power of scrupulous truth-telling and the value of old-style investigative reportage. With the exception of one sagacious patriarch, the Navajo, eager to escape the poverty of the reservation, unquestioningly embraced the mines. The officials charged with ramping up uranium production chose to ignore early evidence of the effects of radioactivity. Researchers assembling that evidence were torn between warning the potential victims and getting the data needed to prove that they were endangered in the first place. The EPA, when it came along, preferred not to stir up requests for a cleanup it couldn't afford, and even the Navajos' own tribal government prevented testing of the land and water in an effort to protect its turf and forestall annoying demands for help. Miners and their descendants, many of whom had grown up in houses without running water or electricity, had a hard time seeing how rocks -- pieces of the very land they revered, could hurt them, especially when the harm only emerged after years of exposure.

It was, ultimately, Pasternak's coverage of the legacy of uranium mining in the Navajo Nation that galvanized Waxman -- who, as a congressman from California, didn't even have a dog in the fight. Following the intricate unfolding of the disaster, it's easy to spot countless points at which a little more information, education and communication (not to mention accountability) might have contributed to saving many lives. That's not a Hollywood story, and there sure isn't a part for Julia Roberts in it, but that's all the more reason why it needs to be told.

Shares