Although it's a bit embarrassing to admit it, who among us doesn't come to great works of literature looking for some hints on improving our own lot? That was the double joke behind Alain de Botton's bestselling "How Proust Can Change Your Life" -- both the absurdity that anyone would turn to one of history's most neurotic, hypochondriacal closet cases for lessons on how to live and the irony that you can actually pick up a few good tips from "In Search of Lost Time."

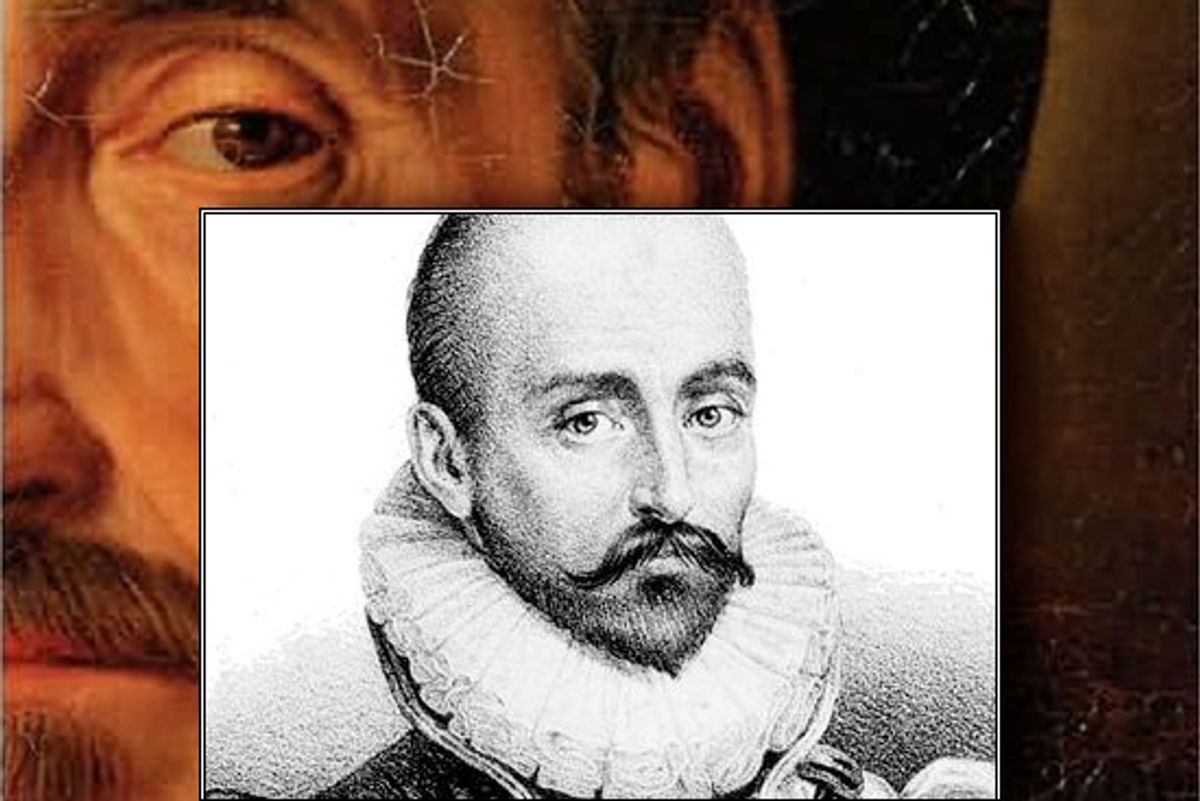

Michel de Montaigne would not look down on you for seeking a little self-help in the pages of his revolutionary opus, "Essays." As described by Sarah Bakewell in her suavely enlightening "How to Live, or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer," Montaigne is, with Walt Whitman, among the most congenial of literary giants, inclined to shrug over the inevitability of human failings and the last man to accuse anyone of self-absorption. His great subject, after all, was himself.

Bakewell, a British writer and librarian, begins with the observation that every generation of readers see themselves in Montaigne, even if they've often had to gloss over certain facts to do it. "To read Montaigne," she writes, "is to experience a series of shocks of familiarity." For a French aristocrat (albeit a country one) he puts on no airs. He confesses that he is lazy and dilatory, the very opposite of self-disciplined: "What I do easily and naturally I can no longer do if I order myself to do it by strict command." He laments the shortness of his stature (and his penis). He notes that he thinks better on his feet ("My mind will not budge unless my legs move it"). He describes stopping his work to play with his cat and thinking, "who knows if I am not a pastime to her more than she is to me?"

Most Renaissance authors seem to be speaking to us across a vast historical and cultural divide; we may find shared experiences there, but we have to work at it. Not so with Montaigne. The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig found a copy of "Essays" while exiled in Latin America during World War II and felt, when reading them, "four hundred years disappear like smoke." This sensation is so powerful that many readers in the centuries after Montaigne's death were compelled to either battle his "seductive" charm or make him over in their own image. Blaise Pascal, an impassioned idealist, deplored Montaigne's pragmatism, his credo of "convenience and calm"; Enlightenment thinkers embraced him as a champion of reason; the Romantics swooned over his devotion to his best friend, Étienne de La Boétie, but then turned around and accused him of insufficient political zeal.

The word Bakewell uses most often to describe her subject's outlook is "nonchalance." Inspired by classical philosophers of the Epicurean, Stoic and Skeptical schools, Montaigne adopted a Zen-like attitude in which everything is subject to doubt and nothing should be taken too seriously. As Bakewell puts it, "He went with the flow." Since he lived his adult life in a France shredded by civil wars and religious extremism, this position was both understandable and rather dangerous. Somehow, Montaigne, whose book became a fashionable bestseller during his own lifetime, managed to survive a fairly successful political career -- he served as the mayor of Bordeaux and ran diplomatic errands for Catherine de'Medici and the king -- although he much preferred to hole up at home and write. (Among the many delightful illustrations in "How to Live" is a photograph of Montaigne's restored study, now a museum.)

Above all, Montaigne invented the personal essay, that unpredictable and strangely addictive literary form devoted, as Bakewell puts it, to "re-creating a sequence of sensations as they felt from the inside, following them from instant to instant." Montaigne constantly revised and expanded "Essays" throughout his life; it was never really finished. "I do not portray being," he wrote, "I portray passing. Not the passing from one age to another ... but from day to day, from minute to minute." Bakewell, who dances from philosophy to history to biography with enviable ease, also has a gift for literary criticism, describing his style thus: "He seems constantly to turn back on himself, thickening and deepening, fold upon fold. The result is a sort of baroque drapery, all billowing and turbulence."

Montaigne's essays can be meandering, yes, and often only tangentially related to their supposed themes. He filled them with anecdotes and examples collected from classical literature but also stories he got from friends and the peasants on his estate. In this and other qualities, he probably had more influence on the free-form English essay than on the lofty, abstraction-prone style of Académie française-sanctioned French. And even back in the day, people complained that he shared too much trivial detail, such as his preference for white wine over red; "Who the hell wants to know what he liked?" one crabby scholar retorted. In the 19th century, Montaigne's candid discussion of carnal matters led concerned editors to produce a bowdlerized version of his works, more suitable for the tender minds of young ladies.

In short, Montaigne was accused of every sin attributed to today's memoirists and bloggers, whose literary great-grandfather he is. Nevertheless, you will find "Essays" in every one of those collections of great books you used to be able to buy by the set, bound in "full genuine leather," with gold lettering. This suggests that the line between trash and literature may be less firmly drawn than some would have us believe, a notion that would probably please Montaigne himself. Or perhaps the real lesson here is that it doesn't really matter what you write about, provided that you do it well.

Shares