Prisons and literature have a long, illustrious shared history, from the classics written behind bars (Boethius' "Consolation of Philosophy," Antonio Gramsci's "Prison Notebooks") to the convicts who turned their lives around via intensive reading — most famously, Malcolm X. A far more tepid recent variation is the prison volunteer memoir, in which an earnest author decides to give something back by teaching writing classes to inmates, an experience that (coincidentally, of course) also makes for much better material than the usual lonely tedium of the writer's life. There are a lot of these books, all following the same basic story line: author cautiously approaches people she expects to find utterly alien, bears witness to their often harrowing autobiographies, and ends up concluding that underneath it all, prisoners (like celebrities, I suppose) are a lot like "us."

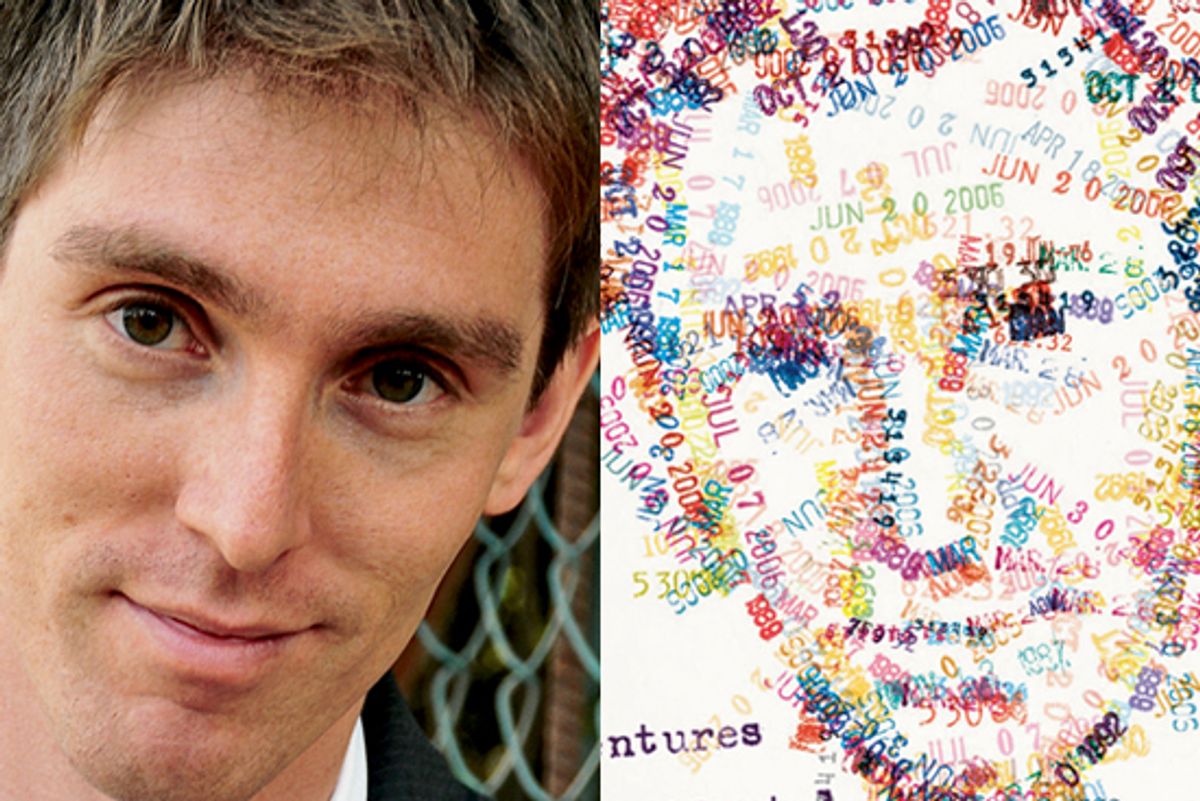

Avi Steinberg's "Running the Books: The Adventures of an Accidental Prison Librarian" is not one of those memoirs. First of all, as he proclaimed to a colleague in a particularly ill-advised moment of Dirty-Harry-quoting bravado, he "works for the city." A feckless graduate of Harvard ("a lovely assisted-living facility from which I'd emerged, like my classmates, stupider and more confident") scraping by on the pittance he earned writing obits for the Boston Globe, Steinberg got an actual job at the Suffolk County House of Correction. A union job, which instantly plunged him into a welter of conflicting loyalties and impulses. He was implicated in a way no brow-furrowing volunteer could ever be, and "Running the Books" presents his experiences working in the prison's library as a fiendishly intricate moral puzzle, sad and scary, yes, but also — and often — very funny.

It helped that Steinberg himself was an outcast, an apostate of Orthodox Judaism who compounded his impiety with "a sin graver even than religious treachery ... professional inadequacy." The fact that this formerly promising yeshiva student could point to an array of Hebrew prophets who'd spent time in the slammer carried no weight with the rabbis. His slackerish ways were "something much worse than worshipping Baal (which at least was an ambitious pursuit)." Yet inside the prison, Steinberg constituted a relative dynamo. On his third day, his union boss told him "You're moving around too much, and you're moving too fast ... Don't work so hard."

The library served both male and female prisoners, but never at the same time: Access was segregated by shifts. Part of Steinberg's job — which included helping inmates do legal and occupational research as well as providing recreational and religious reading materials — was wrangling the front counter, a hangout spot, and scouring the books for contraband letters, known as "kites," slipped between the pages and intended for prisoners of the opposite sex. (The ingenious inmates had also developed an elaborate semaphore system for communicating from their windows across the prison's courtyard. And did you know that you can make a lethal weapon out of a floppy disc or from Scotch tape and sawdust? Steinberg wasn't the only one keeping busy.)

Among the library's regulars were the sagacious Fat Kat, who regarded Hasidim with all the respect due to a notably effective gang — "You did not fuck around in their neighborhood unless you had the green light"; Chudney Franklin, who had a highly articulated and not implausible plan to develop a Food Network cooking show called "Thug Sizzle" (he later changed the title to "Urban Cooking"); and C.C. Too Sweet, a pimp working on his autobiography while earning pocket money from fellow inmates by writing love letters in the style of arrest warrants ("Your sentence is in a maximum security facility called 'MY ARMS.'").

Like many a young American male, Steinberg was smitten with pimp style and lingo — he considered C.C.'s tutelage in "pimp banter" to be "really the only perk of my job." Until, that is, he ran into a former inmate in Dunkin Donuts, traded a little pimp repartee, and then stopped short when they were joined by one of the man's "bitches," also a former library patron, a 20-year-old with a penchant for Frieda Kahlo and a desperate, if thwarted, intention to "do the right thing." "Was I upset simply because I knew the girl?" Steinberg wound up asking himself. "And if I hadn't, would it be OK?" He decided to check C.C.'s record and discovered that the lovable raconteur whose book he was helping to edit had been convicted of kidnapping and raping a 14-year-old.

"Running the Books" is full of such reversals, partly because Steinberg's relationships with the prisoners and his co-workers in the sheriff's department were so unstable. He'd stretch the rules to help someone who seemed deserving, then realize that the seemingly harsh regulations in fact protected him from getting into nightmarish conflicts of interest. Was he a social worker or a jailer? A teacher or a student? Should he dismantle the library's very popular Sylvia Plath shelf because it might encourage suicidal thoughts? Was it significant that the participants in his women's writing group, who insisted on scrutinizing an author's photo before reading the work, gave Flannery O'Connor the thumbs up ("She looks kind of busted up, y'know? She ain't too pretty. I trust her") but nixed Gabriel Garcia Marquez ("That man is a liar")? In a nutshell, were these people wise because they were street-smart, or fools because they were incarcerated?

In the end, a frightening encounter "on the outs" and his own precarious health pushed Steinberg to a crisis, and at that moment he remembered a bit of cryptic advice he'd received from the most forlorn inmate he'd met in prison. Those old Hebrew prophets, he decided, had "crossed the boundary into the realm of the criminal not to comfort themselves by discovering the essential humanity of the criminal — in that Hollywood way of ennobling the prisoner, of dramatizing how they're just like us — but rather to unveil the essential criminal in the human. To expose a darker truth: We're just like them." The Suffolk County House of Correction succeeded at doing what Harvard could not: It showed Steinberg how to grow up.

Shares