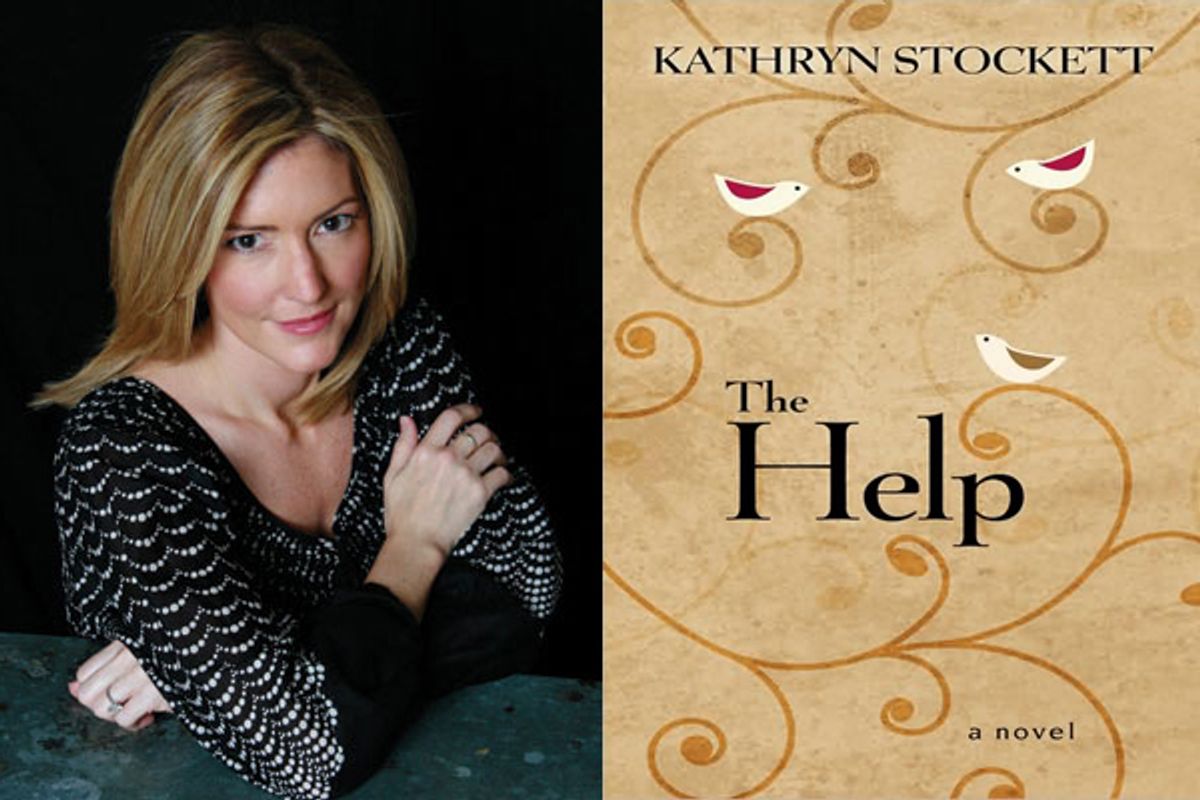

It's inevitable, apparently: Any writer lucky enough to produce a book that spends months on the bestseller list will be sued. So, Kathryn Stockett, come on down!

Stockett is the author of "The Help," a debut novel, first published in 2009, that went on to sell well over 2 million copies. Earlier this month, Ablene Cooper, an African-American maid and baby sitter working in Jackson, Miss., where "The Help" is set, filed suit against Stockett. Cooper accused Stockett of causing her to "experience severe emotional distress, embarrassment, humiliation and outrage" by appropriating "her identity for an unpermitted use and holding her to the public eye in a false light."

At issue is Aibileen Clark, a character in "The Help." Clark is a black woman who works as a maid and baby sitter for a white family in the early 1960s. According to Cooper's lawsuit, the character's first name is pronounced the same as her own, and she and the character are given the same nickname by the children they care for. In addition, the fictional Clark is a middle-aged black woman with a gold tooth, as is Cooper. Cooper's grown son died of cancer; Clark's grown son dies in a workplace accident.

You don't have to have read "The Help" to be perplexed by such a lawsuit -- can a person really claim to be falsely represented by a work that's clearly labeled as fiction? The answer is yes. In 2009, Haywood Smith, the author of another word-of-mouth bestseller, "The Red Hat Club," was ordered by a Georgia state court to pay $100,000 to Vickie Stewart, a former friend who complained of being libeled by the portrayal of a character in that novel. Stewart listed 30 specific points of similarity between herself and the character, but objected to the character being depicted as "lewd," a heavy drinker, a "right wing reactionary" and an atheist.

Such cases are full of bizarre conundrums. The plaintiff must prove 1) that the defamatory fictional character is substantively accurate, otherwise it wouldn't be recognizable as the plaintiff, and 2) that the portrayal makes serious, negative departures from the truth, otherwise it wouldn't be defamatory. (Cooper's is not technically a defamation suit, although it does avail itself of some of the language used in such suits.) The suit against "The Help" also contends that Stockett has repeatedly denied that the character of Aibileen Clark was based on Cooper and at the same time has "appropriated Ablene's name and likeness" for "commercial purposes, namely to sell more copies of 'The Help.'" If Stockett truly managed the contradictory feat of using her novel's connection to Cooper to sell books even as she assiduously covered up that connection, she is much, much more ingenious than a casual reading of "The Help" might lead one to believe.

Those of use who have read "The Help" may also wonder why anyone would be "severely" distressed or outraged to be likened to the noble Aibileen. Although poor and uneducated through no fault of her own, Aibileen is intelligent, brave and kind, apparently without significant flaws. Cooper's lawsuit does manage to unearth two remarks from the novel in which Aibileen seems (arguably) to disparage her own color, but they are tiny scratches on an otherwise glowing portrait. The suit further claims that Cooper finds it "highly offensive" to be "portrayed in 'The Help' as an African-American maid in Jackson, Mississippi who is forced to use a segregated toilet in the garage of her white employer's home."

That last complaint highlights yet another major difficulty for Cooper's case. The issue of the segregated toilet is a key one in the novel; it makes Aibileen angry enough to agree to collaborate with a white woman, a journalist who wants to write a book about the lives of black maids in the town. Stockett has always maintained that she based the character of Aibileen on her own family's African-American maid, Demetrie, who, during Stockett's childhood, used a similar segregated bathroom in her grandfather's house.

This was no doubt a demeaning experience for Demetrie, but it was far from unusual in the South of the 1960s, and it reflects negatively on Stockett's family, rather than on Demetrie herself. If Cooper wasn't subjected to such treatment, that's because she wasn't working as a maid for a white family in 1961, when "The Help" is set; Cooper, who is 60, would have been only 10 at the time. Is the suit complaining that "The Help" is an inaccurate portrayal of Cooper's working conditions when she was the same age as Aibileen, around 54? Of course there are differences, since Cooper was 54 in 2005, not 1961.

As flimsy as the case against Stockett may appear to be on closer consideration, for many it still arouses an instinctive outrage -- if we don't own our own life stories, what do we own? Stockett is white and privileged, and Cooper is poor and black. The racial politics of "The Help" were pretty squicky to begin with, and the idea that Stockett "stole" the biography of her family's maid just makes the whole thing seem outright exploitative. But even if you're uneasy with the notion of a white woman writing a novel purporting to portray how African-Americans viewed families like hers, there's little evidence that Stockett appropriated Cooper's story, as opposed to a couple of her traits and an approximation of her first name.

But wait -- the plot thickens even further. A careful reading of Cooper's lawsuit reveals certain strategically vague spots. Stockett, it claims, "was asked" not to use Ablene's "name or likeness" in "The Help." The document also states that Ablene worked for "the Stockett family." Early reporting on the suit assumed that Ablene worked for Stockett and that she'd asked Stockett directly not to use her name in the novel.

Not so. As Campbell Robertson reported for the New York Times on Thursday, for the last 12 years, Cooper has worked for Stockett's brother and his wife. Cooper also told Robertson that she did not discuss the book with Stockett before it was published. So, presumably, she wasn't the one to ask that her name not be used in it. Here's what Cooper said when Robertson inquired about her employers' role in the suit:

"What she did, they said it was wrong," Ms. Cooper said of the Stocketts, members of a prominent Jackson family. "They came to me and said, 'Ms. Aibee, we love you, we support you,' and they told me to do what I got to do."

Although Robertson refrains from drawing conclusions, his report is suggestive. Although it's difficult to believe that anyone would feel "outrage, revulsion and severe emotional distress" at being identified with the heroic Aibileen, her employer, Miss Leefolt, is another matter.

A vain, status-seeking woman married to a struggling, surly accountant and desperately trying to keep up appearances in front of fellow members of the Jackson Junior League, Miss Leefolt is the one who insists on adding a separate "colored" bathroom to her garage. She does this partly to impress Miss Hilly, the League's alpha Mean Girl (and the novel's villain), but she also talks obsessively about the "different kinds of diseases" that "they" carry. Furthermore, Miss Leefolt is a blithely atrocious mother who ignores and mistreats her infant daughter, speaking wistfully of a vacation when "I hardly had to see [her] at all." Like all of the white women in the novel (except the journalist writing the maids' stories), Miss Leefolt is cartoonishly awful -- and her maid has almost the same name as Stockett's sister-in-law's maid. Fancy that!

As Robertson noted, when Stockett was interviewed by CBS's Katie Couric last year, she revealed that some "close family members" had stopped speaking to her because they were so upset about "The Help." Furthermore, she said, "Not everybody in Jackson, Mississippi's thrilled" with the way the she has depicted the town. The damages sought by Cooper's lawsuit are limited to a modest yet significant $75,000; any more and Stockett could ask that the case be tried in federal court. As it is, the jurors for any trial will be drawn only from Hinds County, which contains the city of Jackson.

We'll probably never know the real story behind Ablene Cooper's lawsuit, but something tells me it's more fascinating than "The Help" itself.

Further reading

Original report in the Jackson Clarion Ledger on the lawsuit against Kathryn Stockett

Blog post containing the text of Cooper v. Stockett Note: The posting's introductory paragraph contains some inaccuracies

Gainesville Times on the libel ruling against the author of "The Red Hat Club"

Shares