Robert Gottlieb has worked in publishing since 1955, when he was hired as an editorial assistant at Simon & Schuster. Over the next few years, under conditions he once self-deprecatingly described as "the kids running the store," he became editor in chief. Later, he was publisher and editor in chief of Alfred A. Knopf and, for five years, the editor in chief of the New Yorker magazine.

The list of books Gottlieb has edited and authors he has worked with is enough to dazzle any reader. In an early coup, he discovered Joseph Heller's "Catch 22," and while working at Knopf he encouraged Toni Morrison to become a full-time novelist. Gottlieb was the editor Bill Clinton requested when it came time to write his own memoirs, and he has also worked on the autobiographies of such entertainment figures as Lauren Bacall, Sidney Poitier, John Lennon and Bob Dylan. The literary works he has edited include books by Ray Bradbury, Salman Rushdie, Janet Malcolm, John Cheever, V.S. Naipaul, Nora Ephron and the historian Robert A. Caro, along with many, many more.

As if these accomplishments weren't enough, Gottlieb made a late-life career change by becoming a writer as well. At the age of 80, he is now the dance critic for the New York Observer, and a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books, where he usually writes about the lives of intriguing cultural figures, deploying his formidable erudition with the lightest of touches. Two of those pieces have evolved into books: "Sarah: A Life of Sarah Bernhardt," " published in 2010, and a book about Charles Dickens and his children, currently a work in progress. He has also published a short biography of the fabled ballet-master of the New York City Ballet, George Balanchine, and edited several anthologies of writings on music and dance.

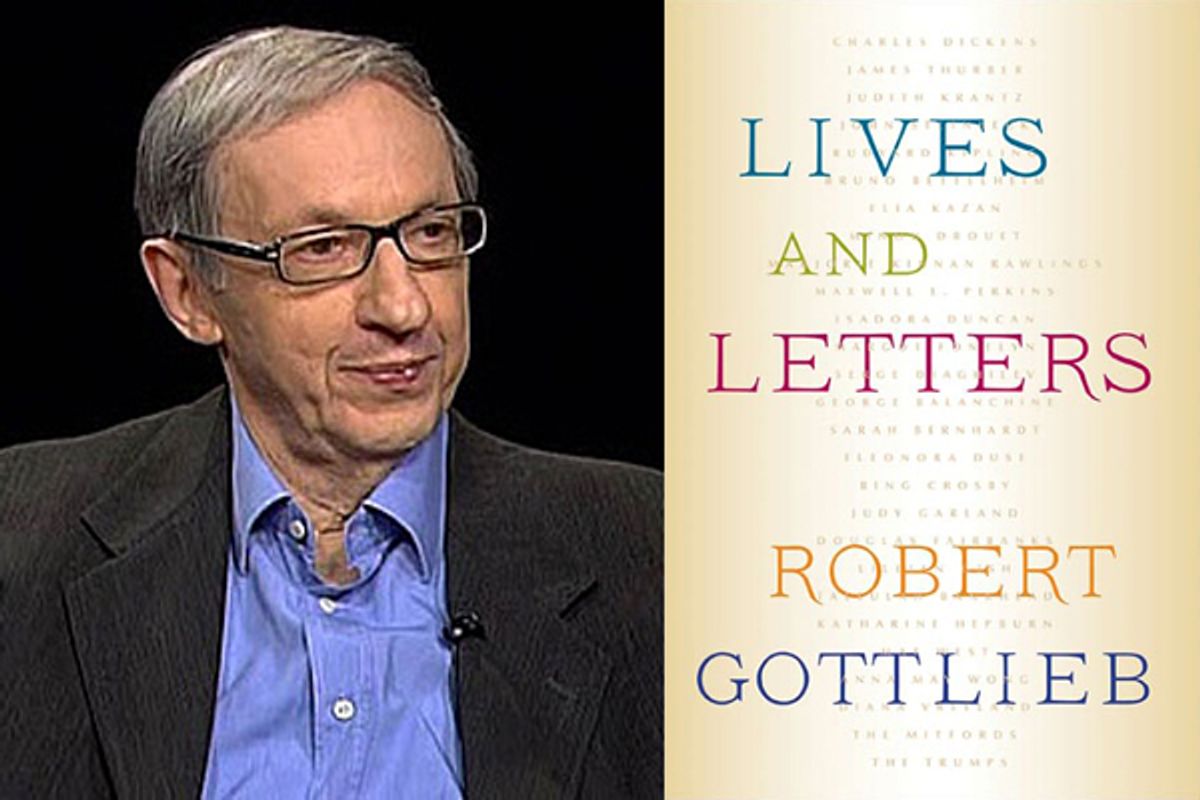

A collection of Gottlieb's biographical articles, "Lives and Letters," has just been published. The book is a browser's delight, rich in both dish and insight, often about people he worked with or knew personally, ranging from James Thurber to Katharine Hepburn. It seems the ideal occasion to talk with Gottlieb about his life and work as an editor and writer.

When did you begin to write seriously?

Writing happened to me. I didn't decide to start writing or to be a writer. I never wanted to be a writer. I don't like writing -- it's so difficult to say what you mean. It's much easier to edit other people's writing and help them say what they mean.

In 1998, Vanity Fair asked me to write a big piece for them on the 50th anniversary of the New York City Ballet. My life, to a great extent, had been spent at and with the New York City Ballet, and I decided to try it. It was very scary, writing about something I loved so much and had such strong opinions about.

Then, Chip McGrath, who had been my deputy at The New Yorker, left the magazine and went to the New York Times to run the Book Review, and then started asking me to write for him. I think his real reason wasn't my writing itself but that I was efficient. With a job like his, that's more than half the battle. Whatever I said I'd do would be done, and done on time. And probably wouldn't need a lot of work because I myself had already edited it. He knew he didn't have to worry.

You also began reviewing books for the New York Observer.

I didn't really want to do it, but the first book that [editor Adam Begley] suggested to me was Michael Korda's publishing memoirs about Simon & Schuster. I had been there when Michael arrived, and he became a kind of protégé of mine, and we were very close for years. So I couldn't resist.

He asked you to review a memoir in which you were a major figure?

Well, of course. This was the New York Observer! That was the whole idea.

I remember I started the review by writing, "This book is so loving and generous to me that I would have had to recuse myself from reviewing it if it wasn't so full of errors that I felt I had to correct them." The day it ran, Michael called me and said, "How could I have made all those mistakes?" And I said, "Because you didn't check anything. Your book is just what I said it is -- a book of fables, a fabulist's book. And you are a fabulous storyteller. Why bother about mere facts?"

You also wrote a piece about James Thurber's letters for the New Yorker.

Again, that made sense because I had grown up on Thurber -- he was my favorite writer when I was 14. And I had for a while been responsible for his books at Simon & Schuster, so I had met him and dealt with him. Also, of course, this involved the history of the New Yorker, of which I had been the editor. So, as with New York City Ballet, I had been both outside and inside the subject.

Now I was writing for all these different places, but I still didn't want to be doing it. I would say to [my wife] Maria, "I can't go on. This is so difficult, so stress-making." And then the next day I would find myself calling [Robert Silvers, editor of the New York Review of Books] and saying, "You know, I notice there's a book coming out on such and such a person and I think I could write about that." Talk about giving oneself mixed signals!

Why do you do it if you don't enjoy it?

The pleasure I get from these pieces, or even in writing my biographies is the pleasure of doing the research. I'm utterly happy when I'm sitting and reading through 12 gigantic volumes of Dickens' correspondence. Making notes, underlining -- it's thrilling! When that's all done, and I've had the satisfaction of taking all this stuff in, then unfortunately comes the moment of horror when I have to digest all of it and figure out a way to start writing. Or not figure out a way -- just start. As I've told generations of writers who have writer's block, "Don't think about writing. Think about typing."

That, for instance, is how I started my Bernhardt book. I had no plan or outline, so I forced myself to sit down and I typed: "Sarah Bernhardt was born in July or September or October of 1844. Or was it 1843? Or even 1841?" That, of course, got me into it, but it also established the tone of the book. From there on it was easy until halfway through when I found that there were two stories -- the story of her career and her art, and the story of her notorious personal life and the world's reaction to it. So I had to stop and think, how do I divide this up? Luckily I have a structural mind, which you have to have if you're an editor, but I can't structure in advance.

I suppose the thing that makes it possible for me to do this is that I just don't think of myself as a writer. I think of myself as an editor. I provide myself with the copy and then I edit it. Look: Whatever gets you through the night.

Were there things that you'd learned from your experience as an editor that someone who had only ever been a writer wouldn't have known?

I don't think I start out with ideas about things. Like all editors, I assume, I'm a reactor.

A common piece of advice given to writers is to turn off your internal editor and just let your writing flow. The idea is that your internalized editor is blocking your creativity.

I don't want to be "creative." I love what I do, which is a service job. I've always said that I want my tombstone to read, "He got it done" -- and then I think, wait a minute: You can say that about Adolf Eichmann. Nevertheless, that's my nature and my temperament. Get it done, whether it's writing the piece or doing the dishes: Do it. Don't sit around moping.

On the other hand, I do sit around moping! When it comes to writing, I can't haul myself to the computer. I put it off all day. Usually around 11 at night, I drag myself over there and I say, "OK, I've got to type something." Then when I'm actually doing it, it's fine. It's not the doing it, it's the getting myself to do it. And then of course, I go over and over and over it.

I've dealt with writers, or observed writers, who aren't like that at all. They're automatic writers. They sit down and they type. I've known three of them, two of whom I was quite close to: Doris Lessing, Anthony Burgess and Updike. You just felt that between the desire and the act fell no shadow. And if they weren't writing, they weren't alive. I guess Updike was alive when he was golfing. But Doris -- whom I've been very connected to for 45 years or so -- she's always said that if she hasn't written during the day she feels she hasn't lived that day. These three were writers the way the rest of us are breathers. But that's not me: For me it's reading that's like breathing.

You write, in your piece about Maxwell Perkins and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, that editing is in the details.

It is, but it's also in the overview. It's both. You have to be able to see a book as a whole, and then you have to step forward and scrutinize.

When I was at the New Yorker I edited a number of pieces, but when I think of myself as an editor, it's as an editor of books. Sometimes, if you're lucky, a manuscript is perfect; you don't have to do anything except say, "Great, well done!" and send it on its way. Sometimes, the problems are cosmetic, and you just have to be careful and point out where the language goes wrong and where there's a contradiction or repetition -- as I say, surface things. But sometimes the problems are structural, and the book just isn't making sense as written. Then one has to sit with the writer and try to figure out how to make it cohere. Other times, alas, there's just no book there. That's a problem. Because, as I like to say, You can take it out, but you can't put it in.

And then there are times when it's just a matter of too much, and you have to convince the writer where it's too much and why it's too much -- perhaps because there's an imbalance. Often, it's a question of the beginning and the end. Sometimes a book starts awkwardly. The writer hasn't revved up and it's stilted. You have to say, "You know, drop the first two paragraphs and you're fine."

Much more radically, when I was first presented with the manuscript for a novel that became a huge bestseller and is still a much-loved book, Chaim Potok's "The Chosen," I was reading it and loving it until I got to a point where I wasn't loving it. I went on reading another 300 manuscript pages or whatever and then called up the agent and said, "I absolutely love this but it's not publishable as it is. Could you tell the writer that I'd be happy to edit and publish it, but only if he grasps that the book ends here, but he's gone on and written a second book. And they don't belong together." Luckily, Chaim agreed.

Do you observe any guidelines about how far to go?

You have to be attuned to what the author's real intention is, because the author doesn't always know. As I've said to hundreds of people when I give speeches on editing or talk to editors: Your job -- short of something radical like the example I just gave you -- is to be in sympathy with what the writer is doing and to try to help her or him make it better of what it is, not to make it into something else. Because that way there will be tears.

Did you make that mistake at first?

Well, I learned my lesson a couple of times. But even when I was doing it, I knew I was making a mistake. It couldn't work. If you're in sympathy with the writer's goal, then unless you're dealing with an hysteric or a paranoid or just a nut case, the writer intuitively senses that and is more than willing to listen and make perhaps not the change that you want but make a change that will get the manuscript to where you would like to see it go. You can't teach editing, though. It's just hopeless. I think I was as good an editor my first day as I am now. Probably better, because I had more energy. I didn't have as much tact, unfortunately. That I had to learn.

For someone so sympathetic to writers, I'm surprised at how far you go to avoid thinking of yourself as a writer.

That's right, I don't think of myself as a writer. But then there's all this evidence that I am one. I've produced books as well as scores of articles and reviews, so finally, I have to say, "I write."

And you're also still editing books.

I'm still editing, particularly books by certain authors I've worked with for many years: Toni Morrison, Robert A. Caro, Nora Ephron. I also work on things that lie in my fields of interest: dance books, film books, biography, history, anthologies.

When the Paris Review wanted to do a long interview with you, you had problems with the idea. Can you explain why?

They had never done an editor, and they said to me, "We want you to be the first one." I said, "Forget about it. On the one hand, editors are insanely egomaniacal and come out sounding like deluded idiots. And on the other hand, a lot of the material is private. It's like the secrets of the confessional. It's nobody's business what I said to A, B or C, thereby rescuing their great books from the total oblivion they would have encountered if I hadn't raised my little finger." Then they said, "What if we talked to some of your writers and then you can bounce off what they say?" And I said that would be fine.

So you feel that the conversations between an editor and a writer about a manuscript are private?

Yes. Now, some writers don't care at all. For instance, I had to stop Joe Heller from giving me too much private credit for "Catch-22." When the New Yorker did a profile of Toni Morrison, Hilton Als wanted to talk with me about the editorial work I had done with Toni and how it had affected her books. I said no. Then he told me, "But she asked me to call you for this information." I hadn't stored up specifics of our editorial sessions, so I called Toni and said, "You have to remind me: What did I tell you?"

But my main advice to Toni wasn't editorial, although that's been a lot of fun. First of all, she's wonderful to work with. We're the same age, we have the same reading experience, and we read the same way, so explanations are not needed: "This, but not this." "I see that. Fine." My major contribution to her was encouraging her early on to liberate herself from her day job, which was being an editor at Random House. I said, "You're a writer. You don't have to do this. There will be enough money. Don't worry."

She was a single mother, right?

She was a mother of two, yes. Editorially, I think the most useful thing I ever said to her was after "Sula." I said, "'Sula' is a perfect book. You don't have to do that again." I said, "Open things up."

It's a perfect book in that it's very controlled?

It's contained and shaped. It's like a sonnet. She didn't have to do that again. And that's when she wrote "Song of Solomon," which is on a whole other scale. Now, the point of this story is not that I'm such a genius. The point is that I was encouraging her to do something she already knew she had to do. That's how an editor can be of real use, if the editor trusts his intuitions.

Intuitions about the writer's career?

Intuitions about reading. And there, I have to say, I do have a strong ego. I trust my reading.

I don't really know what I do as an editor. I've never thought about it, really, except when being interviewed. Because I just do it. It's organic for me, whereas writing is not organic. Which makes it a challenge for me that editing isn't. I'm a fixer. See, my nature is to make things better of what they are.

I've had moments, walking down the street, of seeing a woman walk toward me and wanting to say, "Excuse me madam, you're really great looking, but orange is not your color." But I have restrained myself, wisely no doubt, since as you see, I'm here to tell the tale.

One of the most interesting things you told the Paris Review is that the first thing that a writer wants is for you to get back to them as soon as possible. So many editors don't realize that.

Most don't. And it's torture.

The waiting?

It's torture for people. The few times that it's happened to me as a writer, I've been furious, because you know it doesn't take much time to react promptly. If it's a book, it can be done overnight, at the longest, over the weekend. How long does it take to read a 350 page manuscript? Not long.

You are one of the fastest readers I know.

But you see, when you're doing a first reading of the text that you're professionally involved with, you don't have to read for detail. What the writer is waiting for is your overall impression.

Whether you're a good editor or a bad editor or a non-editor, it doesn't matter: You represent the crucial reading. Yes, his spouse has read it. Yes, her agent has read it. But you represent authority, even if you don't deserve it. You also represent money. And if you have a decent reputation, a writer wants to know what a person with a decent reputation thinks. And of course, if it's a writer you've worked with over the years, it's even more crucial because there's a visceral connection.

Believe me, it's very easy to read 350 pages overnight if you're not doing all the other things that people waste their time on. If you're not watching the latest episode of something. Or going out for drinks with your old buddies. Or walking in the woods. Just sit down and read, and report in. You may say, "There are areas here that we need to talk about. I'm going to go back now and read it editorially." But the anxiety has been dealt with, the writer's anxiety.

This has happened to me with 900-word things. Can some editor really be too busy to read it for six days? What is he doing? I simply don't grasp it. And I also don't grasp how if an editor has assigned something or paid for something, how can he not be motivated by the most intense curiosity? I always want to know right away what the writer has done. Let me at it! Why do I have to have dinner? It's a waste of time. Do I really have to tell the kids a story? (Well, yes.) I've got 500 pages to read tonight!

One thing you hear all the time is about how much editing and publishing have changed over the years. Is that also your impression?

It certainly hasn't changed for me. I'm doing exactly the same thing I was doing in 1956. You know, I don't believe in all this change. Certainly not at good publishing houses. I see younger editors -- they could be 45, or 35, or 22 -- coming in and out of Knopf, where I still have an office. Now, maybe today everything is sent electronically, so they don't have to do what I did, which is to lug the manuscript home and bring it back the next morning, but some still do that, too. They're very devoted. They're very ardent. I think it's one of those myths.

Of course there are lazy editors (and I could name some but won't because of the libel laws) who just never bother to get around to anything. They think their personal priorities are more important than the author's priorities. But that is not what I find in general. The editors I know are devoted to the process and to what they do. I don't know how better to say it.

Certain things have certainly changed in publishing, mostly about delivery systems. And there's been a certain dumbing down of technical editing.

What you mean by "technical editing"?

I think on the whole there may be less copy editing. Although I myself have encountered wonderful copy editors, and I've encountered them everywhere I've published, from Pantheon to Harpers to Yale to Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

I think that when people complain that nobody edits anymore, that's what they're talking about: a less rigorous standard of copy editing. Because the fact of the matter is that most of them are not going to notice the kind of editing that we've been talking about. If something bigger was fixed, they're not going to know that.

Whenever a review says "What this book needed was more editing," it's usually the book you spent the most time editing. That's because its problems were so severe that you've worked the text (and the writer) as far as possible. There comes a moment when either you the editor or you the writer cannot look at it again: It's over, and you have to let it go.

You also mentioned "delivery systems." What do you mean by that?

I don't understand everything that's going on in publishing, the whole issue of e-books and and the different royalty structures and all that. Some people are fascinated by all that, and well they might be, but not me. After 55 years, enough is enough.

Also, since I've been in publishing since the mid-'50s, I've lived through all the moments when doom was cried, going right back to "the medium is the message." The book was dead -- I can't tell you how many times we've buried the book in my lifetime. The fact is that we haven't buried the book, and however all this works out, we're still not going to be burying the book. People are still going to be reading books, and whether they're going to be reading them on a Kindle or as a regular physical hardcover book or a paperback or on their phones or listening to audiobooks, what's the difference? A writer is still sending his or her work to you, and you're absorbing it, and that's reading.

Shares