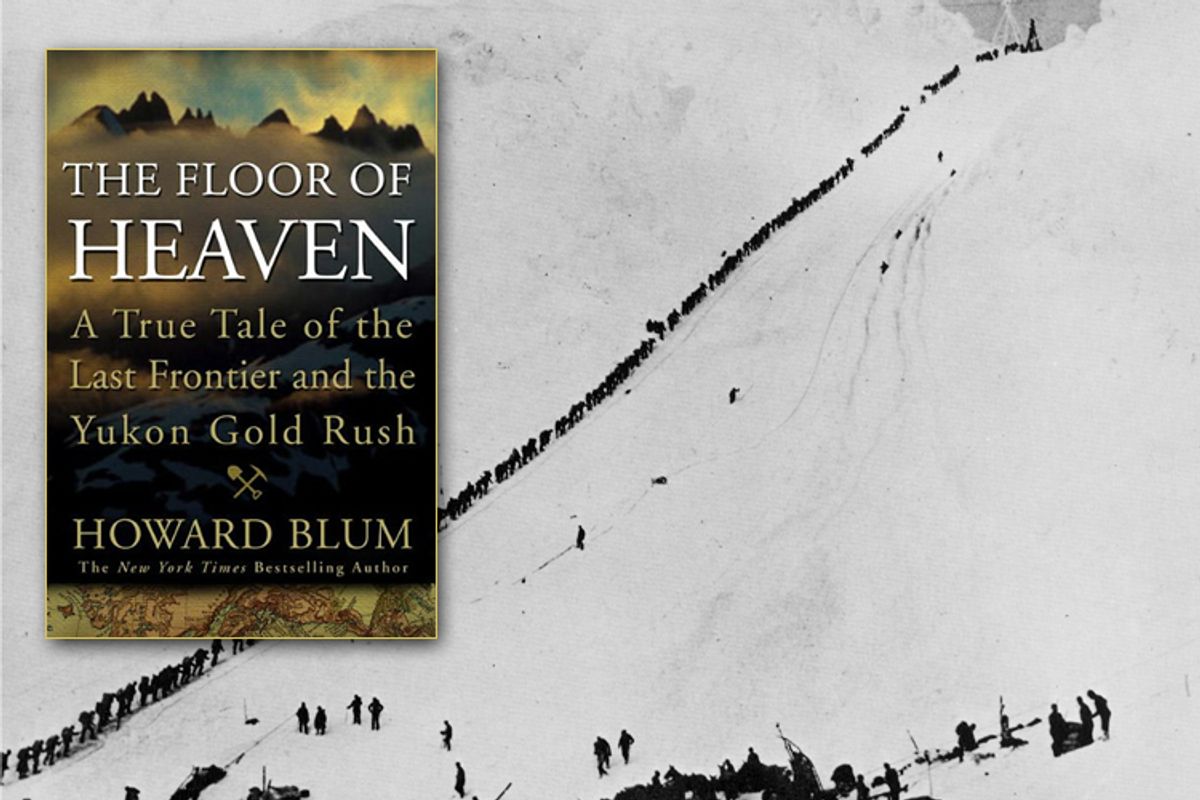

In the summer of 1897, the steamer Portland arrived at a dock in Seattle bearing over two tons of gold and the 68 gleeful prospectors who had discovered it in the Yukon Territory. Well into the fourth year of a grinding economic depression, the populace was electrified. People dropped everything to head to the Klondike, emptying the streets; Seattle's own mayor wired his resignation from onboard a ship headed north. The rest of the world soon heard the news, and thousands of people descended on Alaska that autumn, most of them ill-prepared for the brutal winter conditions and lawless society just south of the arctic circle.

Howard Blum's highly enjoyable "The Floor of Heaven: A True Tale of the American West and the Yukon Gold Rush" is a narrative history set before, during and just after the rush. Blum traces the lives of three storied men -- a prospector, a cowboy turned Pinkerton detective and a notorious conman -- whose fates intersected in an armed confrontation over a stash of gold in 1898. That incident comes fairly late in the book and could even be viewed as somewhat anticlimactic, but getting there is so much fun that it hardly matters. The face-off between Blum's three principals in the harbor of Skagway, Alaska, is really just a pretext for spinning yarns about three remarkable American characters.

Jeff "Soapy" Smith earned his nickname running a racket in which he persuaded crowds to bid on bars of soap that might contain $100 bills. This, however, was only one of the many grifts he mastered (detailed by Blum with considerable relish), from the classic shell game -- learned from a carny named Clubfoot Hall -- to tricking mine owners into signing over controlling interests in their claims to luring rubes into rigged poker games. Soapy also had a genius for leadership, establishing himself as a bunco kingpin in both Denver and a small Colorado boom town before effectively taking over Skagway, the gateway to the Klondike. Among his rackets was a telegraph office that charged new arrivals to exchange telegrams with friends and relatives back in the States; Alaska didn't get its first telegraph lines until four years later.

George Carmack, a Californian, deserted the Marine Corps in the 1880s to prospect in Alaska. Frequently seized by intuitions about where his big strike would come from, he was always wrong, until finally, in 1896, he wasn't. By that time, he had become what whites in the region derisively referred to as a "squaw man," married into the Taglish tribe of Alaskan natives, adopting their dress and learning their language. For a while, Carmack even contemplated becoming chief of his wife's community. He persuaded his brother-in-law, Skookum Jim, and another man to try their hands at prospecting (an activity most natives disdained), and when Jim discovered gold in Bonanza Creek, the three men became millionaires and set off the Yukon Gold Rush.

Charlie Siringo, a former cowboy who could never adjust to the settled life in the fading years, became a detective with the hope it would offer fresh adventures in the waning years of the Wild West. If Siringo often seems like an amalgamation of movie cliches (he even had an "old cow pony" named Whiskey Pete, for crying out loud!), that may be because he helped create them, writing memoirs of his range-riding days and serving as a consultant on the first Western films. His biography provides a fascinating real-life link between the Western genre and what is often seen as its descendant, the hard-boiled detective story.

Siringo's speciality was going undercover, and some of the best parts of "The Floor of Heaven" recount his methods: feigning a broken leg to infiltrate a band of outlaws holed up on a ranch and passing himself off as a mine worker while investigating the theft of gold bars from a warehouse on Admiralty Island in Alaska. The latter case in particular makes for a fascinating 19th-century procedural. Earlier investigators had missed a crucial point that Siringo immediately grasped: Gold is heavy. How did the thieves carry it out of the warehouse and far enough away to sneak it off the island unseen? Later, having figured out the identities of the culprits, Siringo and a colleague had to devise a way to insinuate themselves into the bad guys' confidence to get them to reveal where they'd stashed the loot.

Blum relates all this in an unvarnished, novelistic fashion that enters enthusiastically into the conventions of the Western genre, especially when it comes to the dialog -- be prepared for folks droppin' plenty of g's. Only in his afterward does the author give a sense of how complex the task of assembling "The Floor of Heaven" must have been. Two of his principals made a profession out of lying (even if Soapy did it to commit crimes while Siringo did it to solve them) and the third was known as "Lying George" among his fellow prospectors. Blum's narrative is a fusion of his subjects' (quasi-truthful) memoirs and contemporaneous news accounts as well as letters and memories recorded by bystanders and descendants. It must have been a daunting task wrangling all of these conflicting stories into a single, seamless tale, but you never feel that effort on a single page of this unabashedly entertaining book.

Shares