Jon Ronson is a British journalist who specializes in hanging around with odd people who do odd things. The best-known of his works, "The Men Who Stare at Goats," about U.S. military programs to develop psychological and paranormal warfare techniques, was made into a Hollywood movie. Ronson has produced television and radio documentaries of his own on top of his print journalism, much of it about such cranks as David Icke (who contends that "the secret rulers of the world are giant, blood-drinking, child-sacrificing pedophile lizards that have adopted human form") or fringe-dwelling militants like Thom Robb of the KKK.

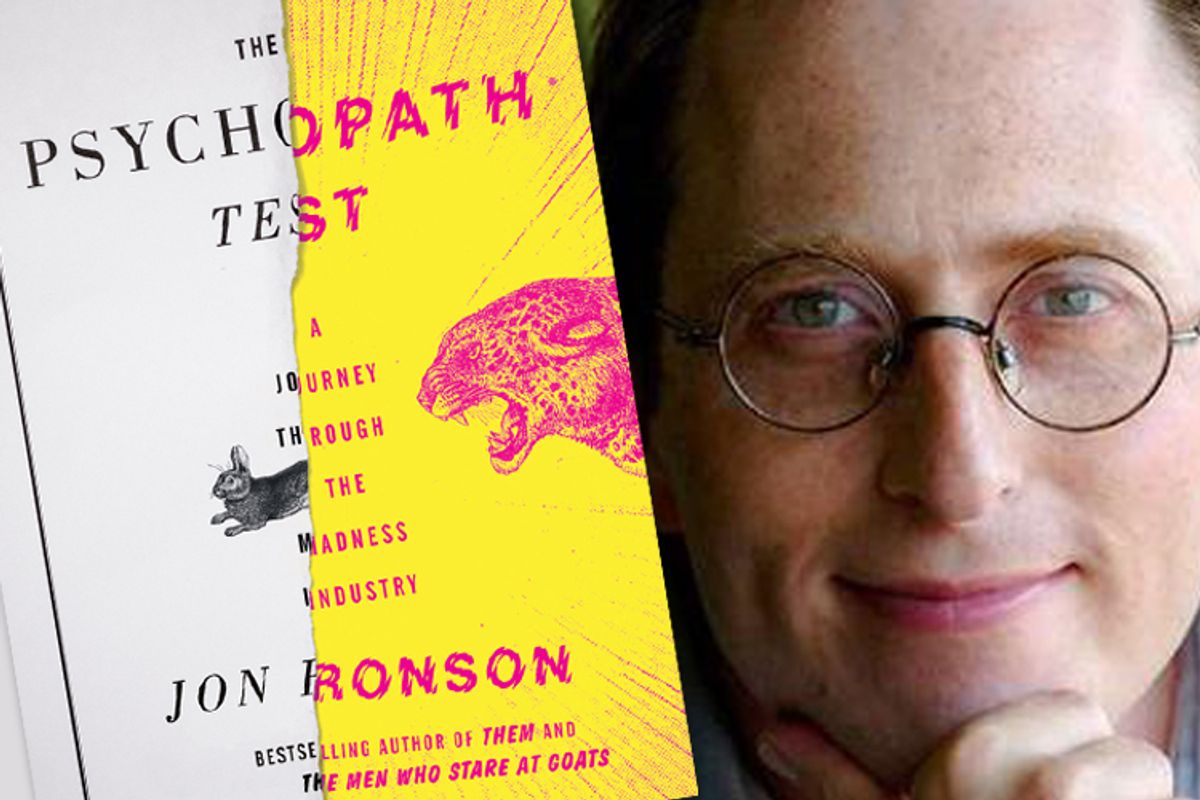

So it was only a matter of time before Ronson graduated from fraternizing with kooks to rubbing elbows with the officially mad, as he does in his new book, "The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry." While working on a story about a Swiss psychiatrist who anonymously sent elaborate puzzle books to several scientists, he became interested in how much the insane can affect the lives and behavior of the sane. Naturally, he went right out and purchased a copy of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, otherwise known as the DSM-IV). A hypochondriacal spiral soon followed. As an antidote, Ronson arranged an interview with an anti-psychiatry Scientologist. The Scientologist in turn introduced him to a man he calls Tony, then imprisoned in Broadmoor, an asylum for the criminally insane.

Tony was sharp-dressed, well-spoken and seemingly trapped in a Catch-22 situation where anything he did was interpreted as an indication that he should never be released into the general population. Convicted of savagely beating a homeless man, he claimed he'd tried to mitigate his sentence by simulating madness, "plagiarizing" statements from such cinematic lunatics as Dennis Hopper in "Blue Velvet" and Malcolm McDowell in "A Clockwork Orange."

Tony was wrong about the sentencing, and Ronson was troubled by the results. It seemed to him that his new acquaintance was unjustly imprisoned, with very little hope of ever getting out. Or that's what Ronson thought until he spoke with a neurologist, who laughed and told him that Tony's whole routine -- from the snazzy suit to the winning manner -- was "classic psychopath." Then she told him about the Hare Checklist, "the gold standard for diagnosing psychopaths," devised by the Canadian psychologist Bob Hare. No. 1 on the list: "Glibness and superficial charm."

Ronson decided to book a spot in a three-day training course run by Hare (something of a guru in the field) and by the end of the weekend he was identifying possible psychopaths right and left, including a Vanity Fair critic who had "always been very rude about my television documentaries." Still, Ronson couldn't entirely withdraw his sympathy from Tony, who maintained, "Trying to prove you're not a psychopath is even harder than trying to prove you're not mentally ill." Although psychopaths are said to be devoid of empathy and remorse, they can be crafty, and are known to study the outward manifestation of emotions in order to ape them. Ronson himself had once interviewed the leader of a Haitian death squad -- certainly a psychopath -- and had watched in acute discomfort as the man obviously faked sobs of regret. Maybe Tony was just a better actor? Or maybe not.

That's how "The Psychopath Test" proceeds, with the excitable Ronson pinging wildly back and forth between finding psychopaths everywhere he looks (he's particularly concerned that many political and business leaders might meet the criteria) and questioning the validity of psychiatric diagnosis itself. He interviews "Chainsaw" Al Dunlap, a notorious business executive famed for the relish with which he laid off tens of thousands of workers in the 1980s (a guy who comes across as pretty psychopathic) and a disgraced psychologist whose facile criminal profiling resulted in the incarceration of an innocent man while the real murderer was free to kill again.

Ronson's touch is light and he's not afraid to play the feckless neurotic for laughs, but that doesn't obscure the serious questions raise by his investigations. Psychiatric diagnoses (and, these days, the medications that follow) really can become fads, with certain experts suddenly deciding that multiple personality disorder or childhood bipolar disorder are far more common that ever before suspected. Ronson even finds the occasion for a little professional soul-searching; he accuses himself and other journalists of being the Goldilocks of craziness, seeking out people to write about who are just nuts enough to be colorful but not so disturbed that they're downright sad.

What "The Psychopath Test" is not, however, is conclusive; conclusiveness is pretty much the opposite of Ronson's brief in this outing. Much of the time, he leaves the reader remarkably free to draw his or her own conclusions by presenting certain facts while refraining from comment. For those willing to think for themselves, this makes for a refreshing change. There are some who may find Ronson's restraint unsatisfying, but in an age when the worst are filled with the passionate intensity of complete conviction, a little doubt might do us all some good.

Shares